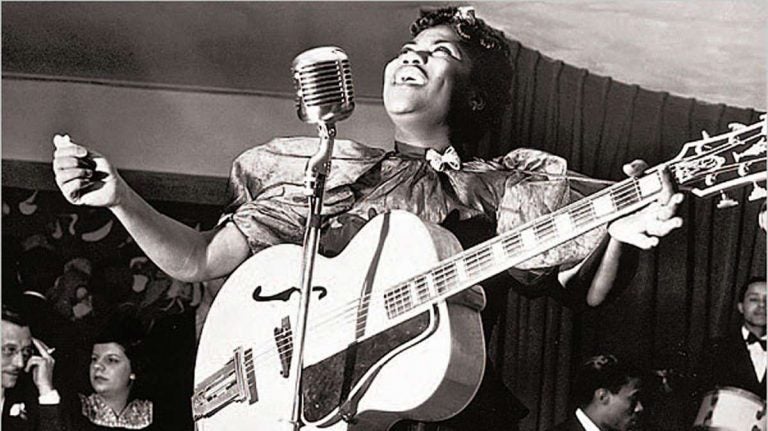

Rosetta Tharpe bridged sacred and secular music with a wicked guitar

Sister Rosetta Tharpe is considered ''The Godmother of Rock and Roll,'' for her contribution to the creation of rock as a guitar-playing gospel star from the 1930s to the ‘60s, with Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, Little Richard and Chuck Berry citing her as an inspiration. She died in Philadelphia in 1973. (Philadelphia Music Alliance)

It took a long time in American music history to recognize the impact Sister Rosetta Tharpe had on rock ‘n’ roll and gospel. Her guitar style, distilled from many African-American traditions, a voice that would cross from the sacred to the secular, and a memorable stage presence are now the subject of a PBS American Masters documentary.

She spent the last 15 years of her life in Philadelphia, traveling to perform in major hubs for gospel music.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe didn’t do anything the conventional way. At 9 years old, she started traveling the gospel circuit, following her mother from one Church Of God in Christ to another, all the way from Arkansas, where she was born in 1915, to Chicago.

She was the soulful carrier of spiritual messages but she also sang at Harlem’s Cotton Club and was forgiven for the trespasses because of her showmanship, extraordinary voice and rocking guitar.

So, there’s a good reason for calling Tharpe the “godmother of rock ‘n’ roll,” says Gayle Wald, the author of the Tharpe biography, “Shout Sister Shout.”

“She picked up the electric guitar relatively early in its invention and figured out a way to give the instrument a voice, that was separate and distinct but complementary to the singer’s voice,” said Wald. “So you can hear a musician who’s working two voices at the same time and taking an aesthetic that came from the church where call and response is so important.”

That style had a profound influence on musicians ranging from Chuck Berry to Elvis Presley to Bob Dylan and every rock guitarist since then.

The Philadelphia Years

By the time Tharpe moved to Philadelphia in 1962, she was one of the most famous gospel singers in the country. She had an extraordinary presence, says Ira Tucker Jr. Tharpe played with Tucker’s father, founder of the gospel group the Dixie Hummingbirds.

“She was a wonderful person, she was an artist,” Tucker said. “She reminds me of what Lady Gaga is today. That’s what she was in gospel music. When I see pictures of Rosetta, today, I see the color of hair, the orange the fiery red, the blond. She was quite an entertainer and quite a personality. She was very high key and a lot of up energy.”

Tharpe bought a house in Yorktown, a new African-American middle-class neighborhood in North Philadelphia and literally held court for the constant flow of admirers and neighbors. She joined Clara Ward and Marion Williams as gospel royalty in Philadelphia. Tucker says she succeeded against the odds of the time.

“Because she was a woman, and that was a time when females didn’t make it on their own in the entertainment business, especially black. And doing gospel music, you were already down a line,” Tucker said. “So she had to make a living, and she did. She was way ahead of her time and they loved her. And we all loved her too because she was like Hollywood to us.”

For years, Tharpe remained somewhat forgotten as interest in gospel recordings began to wane in the late 1970s and her diabetes began to take its toll. She died in 1973 of a stroke after one of her legs had to be amputated. She sang about being tired and weary in her last performance.

Rosetta Tharpe was buried in an unmarked grave. It took eight years to carve her name in a tombstone and only in 2011, a plaque was unveiled in front of her house in North Philly in a ceremony that brought neighbors, friends, admirers and followers of her music tradition.

In the American Masters series documentary, one of her best friends says, through it all, Tharpe was devoted to her religious roots.

“Rosetta would sing until she made us cry, she would sing until she made us dance for joy. She kept the church alive and the saints rejoicing,” she remembered.

“American Masters: Rosetta Tharpe, the Godmother of Rock and Roll” airs Feb. 22 at 9 p.m. on WHYY-TV

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.