Residents of Philly homeless encampments prepare to resist eviction

Despite a 9 a.m. deadline, camp organizers say Philadelphia has not done enough to help those living in the tents and they’ll fight to stay.

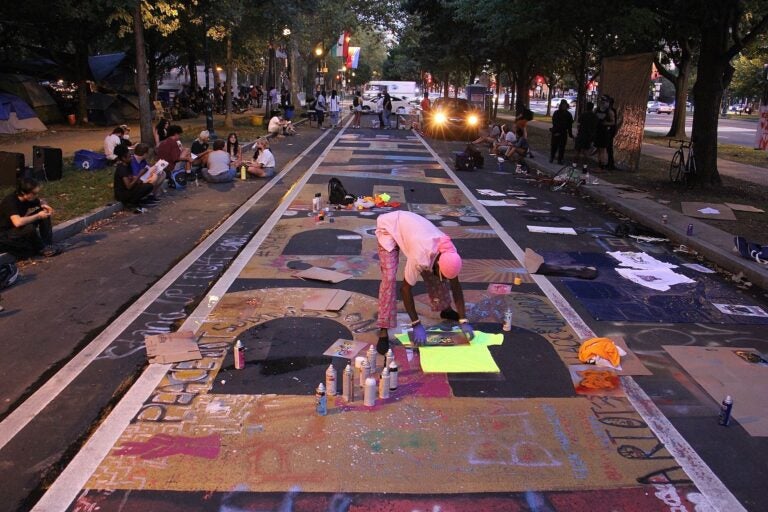

Protesters gather on the Ben Franklin Parkway, where a homeless encampment is under notice from the city that it will be cleared. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

About 100 people who have been living in tents for some three months along Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway are getting ready for what may be their eviction.

The city has given them a deadline — the third, and likely the last deadline — to vacate the area by 9 a.m. Wednesday. A similar deadline has been posted at a smaller Ridge Avenue encampment on property that is owned by the Philadelphia Housing Authority and is slated for development.

Residents of this encampment on the Ben Franklin Parkway are bracing for tomorrow morning. The city says at 9 a.m. it’s enforcing an eviction notice on the hundred or so people living here, and on those living at a smaller camp in North Philly. pic.twitter.com/QvFMHcD2mW

— Katie Meyer (@katieemeyer4) September 8, 2020

The encampment sprang up in June as a protest against the lack of affordable housing options in the city, and gave voice to some of the roughly 5,500 Philly residents who experience homelessness every year.

Attorneys working on behalf of encampment residents attempted to get the city’s eviction order thrown out on the grounds that it violated their constitutional rights to protest. But a federal judge upheld the order late last month.

The judge ruled that as long as the city gives the people living in the camps 72 hours’ notice, it has free rein to clear the encampments.

What that might look like remains an open question.

Mike Dunn, a spokesperson for Mayor Jim Kenney’s office, said Tuesday morning that it would be a “a continuation of, and an elevation of, what the city has done for many weeks.”

Officials plan to offer aid and alternative housing to camp residents, and will be newly supplementing those efforts with “navigators” who will give the residents counseling on their options. But when asked what would happen to people who don’t take those options and try to stay at the camp, Dunn said he was “not getting into hypotheticals.”

“We still hope that those in the camp will voluntarily decamp, and avail themselves of the services being offered,” he said in an email. “Our goal is still a peaceful resolution … We urge the leaders of the protest camp to allow outreach workers to offer these supports tomorrow to those living in the encampments.”

But Jennifer Bennetch, a camp organizer, and a resident at the Ridge Avenue encampment said she doesn’t think the city has done enough to help the people living in the tents, and says they’ll fight to stay.

Nasir Bell & Christopher Bowman got involved after they noticed the tents during a Juneteenth protest. Bell says they’ll be here tomorrow. “If the city was knocking on your door for no other reason than it’s a hindrance or doesn’t look nice, would you leave? I know I wouldn’t.” pic.twitter.com/kJOxQfDCuD

— Katie Meyer (@katieemeyer4) September 8, 2020

Organizers say that, as far as they’re concerned, the city has plenty of empty housing that could be turned over to people without homes.

At a press conference earlier Tuesday, organizers with ACT UP Philadelphia and Philly Housing Action said that while they’re happy with some of the steps the city has taken to help people who need housing and can’t afford it, they don’t think officials are being transparent enough, or taking their efforts to house people far enough.

As the conflict over the encampments has dragged on, the city has used CARES Act funding to provide 260 hotel rooms at COVID-19 prevention sites for people at particular risk for contracting the virus. As of last week, 111 people living in the encampments had accepted city housing at those sites, residential treatment centers or shelters.

City officials and the Philadelphia Housing Authority also say they’re working on longer-term plans aimed at making housing more affordable, including using federal funds to create 900 to 1,400 long-term housing units for people who currently don’t have places to live, have very low incomes, or have disabilities.

The city said it also plans to pilot a “Tiny House Village” and is working to establish what it’s calling a Rapid Rehousing Program, which would give up to two years of rental assistance to people who currently live on the street.

“The protests have brought new attention to the magnitude of the suffering endured, primarily by Black Philadelphians, and I appreciate all involved for shining a spotlight on this critical issue,” Mayor Kenney said in an Aug. 31 statement. “However, for the health and safety of all involved, including the surrounding community, we can no longer allow the camps to continue.”

Several groups attached to the encampments, however, issued a statement saying they believe use of police and city workers to seize belongings or physically force residents to leave the encampment is “state-sanctioned violence being used to solve problems that resources would be better able to solve.”

They also say a city plan to make vacant housing available through community land trusts needs to go further, and that people currently living in abandoned homes need a clearer path to legal residency or ownership.

Indigo, 20, was living in Temple dorms before the semester ended and he had to leave. He’s been back and forth between the Ridge Ave settlement and this one since. He says tomorrow, he’ll be trying to support his friends. “Where else are we going to go?“ pic.twitter.com/AoEg0MvrAE

— Katie Meyer (@katieemeyer4) September 8, 2020

Most Parkway encampment residents WHYY News spoke to Tuesday night said they didn’t know what to expect Wednesday morning.

Indigo, 20, said he was living in Temple University dorms before the semester ended and he had to leave. He’s been back and forth between the Ridge Avenue settlement and the one on the Parkway ever since.

He said tomorrow, he’ll be trying to support his friends.

“Where else are we going to go?”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.