Racial disparities in Philly prisons persist, despite 47% decline in incarcerated population

A local nonprofit has proposed some solutions to help curb the trend.

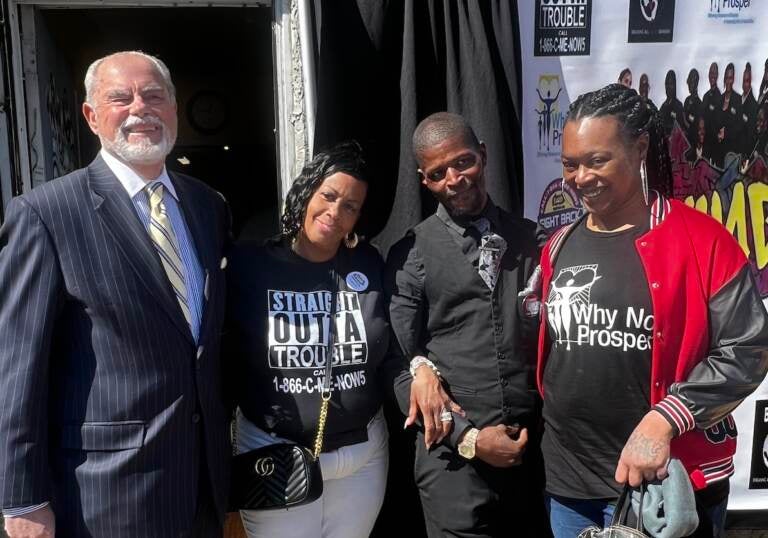

Byron Cotter, Michelle Anne Simmons, Marcus Pearson and Delia Avery at the launch event for a new probation assistance program from Why Not Prosper, an organization aiming to reduce racial disparities in Philadelphia prisons. (Photo courtesy of Michelle Anne Simmons)

A Philadelphia nonprofit that works with formerly incarcerated women is on a mission to reduce racial disparities in the city’s jail and prison populations. Why Not Prosper has laid out recommendations in a new report out this week, produced in partnership with the city of Philadelphia as part of a federal grant challenge.

The John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety + Justice Challenge provides funding to 57 cities, counties, and states to reform their criminal justice systems and reduce racial disparities. As of February 2022, Black Philadelphians make up 73% of the prison population while white residents make up just 8.5%, according to data from the First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, though both groups comprise about 44% of the city population.

“We’re dealing with an unjust system, we’re dealing with racial inequalities as it relates to these systems, and so we want to navigate that together and help people become legalized,” said Rev. Michelle Anne Simmons, Why Not Prosper’s founder. “Because the lack of knowledge is the reason why people perish.”

Philadelphia was selected for the federal initiative in 2016 and has received nearly $11 million to tackle seven goals:

- Reduce the number of people incarcerated pretrial

- Create efficiencies in case processing that reduce length of stay

- Reduce the number of people held in jail on a probation detainer

- Reduce racial and ethnic disparities across the criminal justice system

- Reduce the number of people in jail with mental illness

- Increase cross-system data capacity

- Foster meaningful community engagement

Philadelphia’s prison population is down 47% since 2015, according to 2022 data from the city’s Office of Criminal Justice. But the population fell 57% for white people and only 40% for Black people, and Black Philadelphians actually make up slightly more of the prison population now than they did in 2015.

Why Not Prosper was selected as one of the program’s “racial equity cohorts,” and has spent the last year learning about this problem and exploring solutions through community surveys, focus groups, and town halls. Their report out this week finds that there is a lack of education among people on probation about how to avoid violations that lead to more serious consequences.

“People are running around, scared to talk to the PO, now running from the police, now have an open warrant,” she said. “That’s what the studies say, and most of those people that’s scared … are Black people. And that’s because we’re overpoliced.”

The report, produced with help from Bryn Mawr College, featured commentary from individuals currently or formerly incarcerated or placed on probation. It found that people navigating the legal system were often not aware of the processes and procedures surrounding the terms of their probation, and that “tightly controlled, difficult to understand information can enable repeated victimization of Black and brown people by those with power.”

Based on information gathered through the report, Simmons’s group is launching the “Straight Outta Trouble” program, which strives to educate people who are on probation so they don’t violate their sentencing conditions and end up behind bars. The program offers to refer community members to the Defender Association of Philadelphia to help them get back on track if they are in violation, or seek out early termination of probation if they are eligible.

Paul Heaton, a professor and academic director of the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at the University of Pennsylvania, said high caseloads are partially to blame for the continued over-incarceration of Black residents.

“Implicit bias can easily manifest when you have a lot of cases and don’t have a lot of time to consider someone’s situation,” he said.

He said part of the reason that the report found a dip in the overall prison population but no dent in the racial disparities is because some interventions, such as diversion programs, are of bigger benefit to white offenders. Black offenders are more likely to have criminal histories that exclude them from diversion options, he added.

“There’s a lot of reason to think the system is too large and diversion would be beneficial,” he said. “But if certain communities are disproportionately policed … people from those communities are going to be less eligible.”

His own work has shown that bail advocate programs, which assign paralegals to help public defenders fight for release after an arrest, have successfully reduced the likelihood of detention while offenders await trial.

Why Not Prosper’s report also makes the following recommendations:

- Improve access to mental health in the pre-entry period and during incarceration

- Review criminal legal system funding priorities to document outcomes and disparities, identify what is working and what is not, and define ways to reallocate funding consistent with the findings and recommendations presented in the report

- Increase investments in technology and education to bring greater clarity to the criminal legal system, its processes, and its outcomes, beginning with probation

- Partnering with local nonprofits and community groups, including Why Not Prosper and the Safety + Justice Challenge Community Advisory Committee, to facilitate town hall meetings and other educational sessions on rights, responsibilities, and processes for people involved with the criminal legal system

Additional resources for navigating the criminal justice system can be found online.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.