‘I’m just trying to survive’: Outreach workers rush to get unsheltered Philadelphians inside during Code Blue

When a person’s heart has stopped due to cold, hospitals pump warm liquid into the space around their lungs to try to revive them.

Listen 4:23

Project Home mobile assessor Jovan Cosby in the call center at their location in Center City. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This story is from Young, Unhoused and Unseen, a podcast production from WHYY News and Temple University’s Logan Center for Urban Investigative Reporting.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

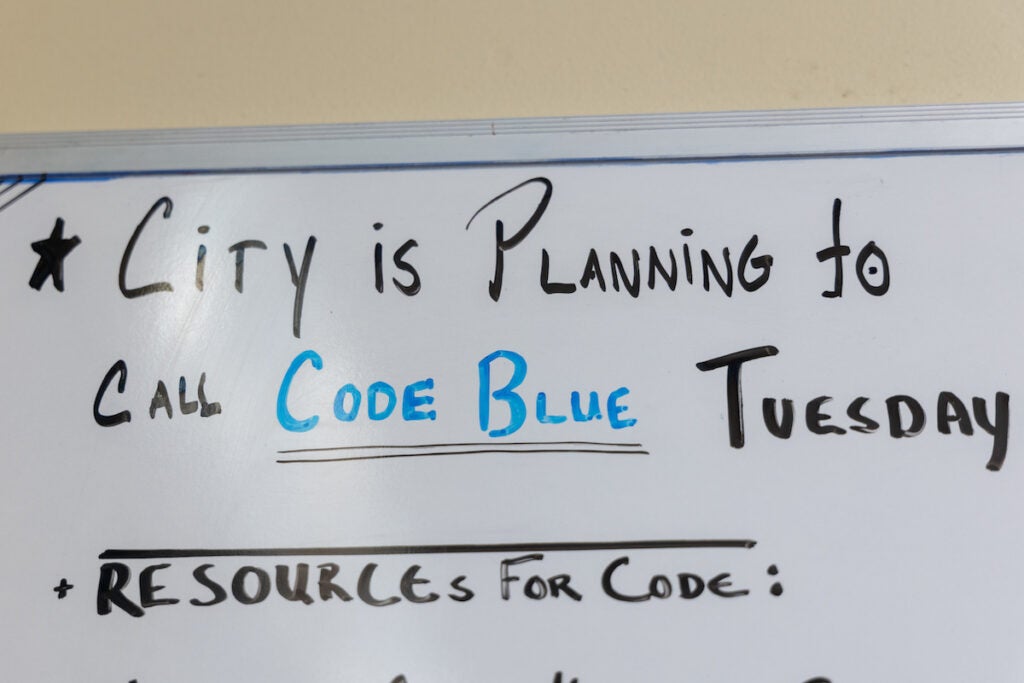

Windchill in Philadelphia is expected to near 20 degrees in the early hours of Dec. 20. The city’s “Code Blue” warning is in effect, with the hopes of saving lives.

It was about an hour after sunset, and the temperature was dropping.

Tony Reed sat on the sidewalk beside his wife, who was almost invisible under a blanket.

Scattered around them laid old household appliances and furniture — discarded objects Reed collects and repairs to earn money. Wooden pallets turned on their ends formed makeshift walls around the couple, but offered little protection from the wind. The underbelly of I-95 loomed overhead, obscuring the dark night sky.

“As long as we’re under the blankets, I guess we should probably be alright,” Reed said.

Reed layered a gray coat over his sweatshirt. His clothes were still damp from a few days before, when the wind had blown rain sideways under the overpass, leaving Reed and his wife in “puddles.”

“With the weather being cold — yeah, it was bad,” he said. “We’re all still trying to get over that. I still got the chills and everything.”

Hours before Reed and his wife hunkered down for the night beneath the overpass in Port Richmond last Wednesday, the city called a Code Blue — meaning weather conditions made it particularly dangerous for the hundreds of unsheltered Philadelphians to be outside.

“It’d be great to have more clothes, but I can’t do nothing about it,” Reed said. “It is what it is.”

Sleeping outside can be deadly

Homelessness is dangerous year round. But during the winter, it can be especially deadly.

Around 700 people live unsheltered in Philadelphia, according to this year’s “point in time” count, a measure that’s generally considered an underestimate. So far this year, at least 12 people have died from exposure to cold. Last year, that count stood higher than two dozen.

During the winter, emergency departments see unhoused Philadelphians come in with cold-related injuries or illness, ranging from frost “nip” to hypothermia, on a daily basis, said Dr. Betsy Datner, chair of emergency medicine at Jefferson Health.

“We see patients who sometimes shock us with how cold they are,” said Dr. Claire Abramoff, an attending physician in the emergency department at Jefferson Einstein Hospital in the Logan neighborhood. “They’ll walk into the emergency department, maybe be a little confused, and then we’ll check [their] temperature and they will be 90 or 89 degrees Fahrenheit.”

At this stage of hypothermia, symptoms include clumsiness, a weak pulse, and poor judgment. As the body temperature drops, people can experience hallucinations, slurred speech, loss of consciousness, fluid in the lungs, and finally, cardiac arrest.

Frostbite becomes a risk when the temperature hits freezing. But hypothermia, when body temperature dips below 95 degrees Fahrenheit, can set in at higher temperatures when wearing wet clothes.

This is why sleeping on steam grates can be surprisingly dangerous, said Jovan Cosby, a mobile housing assessor at the nonprofit Project HOME. Steam grates feel warm, but leave clothing damp.

“A lot of times they don’t even know they’re wet,” Cosby said. “Sometimes when we help them up, their clothes will be soaking wet.”

Abramoff sees cold-related injuries throughout the winter, even outside of Code Blue declarations. These injuries can have long-term, devastating effects for unhoused people.

Superficial frost “nip,” which Abramoff compares to a sunburn, can heal on its own if you can get inside, warm, and dry quickly. If not, it can progress to severe frostbite, leading to chronic pain, numbness, and other issues.

Medical staff at Einstein rewarm frostbitten limbs slowly in room-temperature water — a process that can be painful enough for patients to require pain medication, Abramoff said.

“If it continues to progress and we aren’t able to intervene, it can lead to gangrene, loss of digits, loss of the foot,” she said.

In cases where a person’s heart has stopped due to cold, staff pump warm liquid into the cavity around their lungs, into their bladder, and sometimes into their stomach, Abramoff said.

Abramoff thinks the number of unsheltered Philadelphians who experience injuries or illness from the cold is likely far higher than what emergency departments see.

“A lot of the patients experiencing homelessness have a lot of fear of the health care system, fear of shelters,” she said. “I think a lot of these people unfortunately suffer from cold-related exposure and injury that we just don’t know about.”

Rushing to get people inside

The City of Philadelphia declares a Code Blue when temperatures dip below freezing with rain or snow, or when wind chill causes the temperature to feel near or below 20 degrees.

Outreach workers from various organizations ramp up their operations, and shelter intake protocols can be reduced to get more people inside faster, said David Holloman, interim executive director of the Philadelphia Office of Homeless Services. Over the past four winters, close to 900 people have been placed in emergency shelters on Code Blue nights, according to a city report.

“It’s a life-saving event,” Holloman said.

On a Code Blue night, phones can ring back-to-back at Project HOME’s Outreach Coordination Center in North Philly, where dispatchers answer calls to the 24/7 homeless hotline. Concerned passersby call about people living outside, residents at risk of losing housing call seeking resources, and people experiencing homelessness call asking about shelter options.

During a particularly severe Code Blue last Christmas Eve, 750 people called the hotline in a single day.

Outreach workers drive around the city in groups of two or three, responding to these calls and checking in on people they know may be particularly vulnerable to the cold.

“We will focus on individuals we know have significant barriers to shelter,” said Jonathan Juckett, senior program manager for the Outreach Coordination Center at Project HOME. “That includes individuals with opioid use disorder who may not have the ability themselves to make it into shelter… but also individuals with pets living on the street or couples that may not have access to shelter and not want to split up from their partner.”

Outreach shifts extend by one hour during Code Blues, to cover gaps during shift changes. Nonprofits and the city may also call in additional outreach workers, to provide greater coverage on the overnight shift, Juckett said.

After last Wednesday’s Code Blue declaration kicked in, Project HOME mobile housing assessor Jovan Cosby set out in a white van toward Center City, looking for a woman an outreach worker reported not wearing enough clothes.

On the way, Cosby came upon several other people sitting on street corners or steam grates. He parked next to a man sitting on the sidewalk, holding a homemade cardboard sign.

“If you ever felt you want to get out of the elements just for the night, or it becomes too unbearable, you can call the hotline number,” Cosby told him.

Many people living outside aren’t aware when a Code Blue is declared, Cosby said — especially if they don’t have a cell phone.

The man sitting on the sidewalk asked Cosby for a hat and gloves. Cosby searched through the supplies in the back of the van and came up empty, but gave him hand warmers, socks, and a “Where To Turn” sheet with the hotline number and a list of resources. Cosby returned later that night with a hat, he said.

“One thing that we’re always taught is never make false promises,” Cosby said. “If you tell somebody you’re gonna be out with a hat, make sure you’ll be back out with the hat.”

A few blocks away, Cosby stopped to introduce himself to another man sitting on the street corner.

“Our friend John wasn’t interested in any services,” Cosby said after they talked for a few minutes. “But a lot of times I just like to break that barrier and just build that rapport there, just in case if he ever becomes interested in any services.”

Cosby then headed up to Port Richmond, to deliver blankets and hand warmers to Tony Reed, his wife, and some others living nearby.

On a typical night, an outreach worker might talk to dozens of people living outside and transport up to around ten to a shelter — but still not have time to talk to every person they see living outside. Cosby said this is the hardest part of being an outreach worker. On Code Blue nights, it’s a balancing act to try to get to the people most in need.

“I think that speaks volumes about the numbers that’s on the streets,” Cosby said. “There’s times where I would love to engage someone but I know I have to get to this call. [I’ve] kind of got to weigh my options. Basically… what’s the vulnerability status of this person?”

More shelter beds, but not enough for everyone

Porsha Andino was living outside last Christmas, when the temperature dropped to just 18 degrees Fahrenheit.

Andino is a member of Project Safe, a Kensington-based mutual aid group focused on harm reduction for women and queer people. She’s been unhoused in the neighborhood for roughly two years.

As extreme cold set in late last December, Andino said she was not able to get into shelter. She ended up falling asleep outside.

When she woke up, her shoes were frozen to her feet.

“I was numb,” she said.

A few days later, Andino checked herself into a hospital. She heard she’d need an amputation — first her toes, then up to her calf.

It took months to recover from the two surgeries and skin graft she needed as a result of the frostbite, she said. She now uses a manual wheelchair to get around, and as of early December, had been unsuccessful getting disability benefits, shelter, or housing. She said since losing part of her leg, it’s been harder to endure the cold.

“I wish there was more help,” Andino said.

There are roughly 3,700 year-round emergency shelter beds in Philadelphia, plus 250 to 300 additional beds for the winter season. During Code Blue declarations, up to 300 more beds can come online, and emergency shelters allow people to stay through the day — rather than just overnight.

Even with this additional space, it can sometimes be hard for outreach workers to find shelter placements for people — particularly women and families, Cosby said.

“I’m pretty sure every outreach worker has experienced some type of pushback when it comes to getting someone in on a Code Blue night,” Cosby said.

Just as shelter capacity increases during cold weather, so does demand, said Candice Player, vice president of outreach and special initiatives at Project HOME.

“There are just never enough beds,” Player said. “For dispatchers who have to answer the phone and say to a person on the other end of that line, we’re doing our best but right now they’re having a hard time finding a bed, … really, really is awful. Or for an outreach worker to have to say to someone in the street, right now your best bet might be to go to a subway station or an emergency room or a police department — we never want to do that.”

Philly’s shelter system is usually able to meet the daily demand for shelter beds, Sherylle Linton Jones, a spokesperson for the Philadelphia Office of Homeless Services, wrote in an email.

Jones said the shelter system did not hit capacity last December 24 or 25. But if everyone living on the streets tried to access shelter at the same time, capacity would not meet that demand, she said.

“If everyone in the city of Philadelphia wanted to go into shelter, it would be impossible to place everyone,” Cosby said.

‘I didn’t choose this’

Despite the risks of sleeping outside in frigid temperatures with damp clothes, Tony Reed and his wife did not plan to access shelter during last Wednesday’s Code Blue.

Reed worried they wouldn’t be able to find placement together as a couple, and feared leaving the salvaged belongings that have become their livelihood. The couple has lived in a car, in a tent, and on the sidewalk since getting booted out of a family member’s subsidized apartment in Delaware County last year. They are frightened of the things they’ve heard about shelters.

“You know, people stealing from each other,” Reed said.

To Cosby, it’s difficult to see people outside in potentially deadly conditions. But everyone has a right to pass up services that don’t work for them, he said. He pushes back against the idea that people choose to be homeless.

“It’s [a] human right to say what you want to accept and what you don’t want to accept,” Cosby said. “Why do I have to settle for something I feel as though is less, just because it’s offered to me? … People have that stigma that if a person is offered shelter and they don’t take it, they must not want the housing — which is certainly not true.”

Reed said services and housing need to be more accessible and available. He said living outside means dealing with encampment sweeps and the risk of harassment by civilians. He wishes people would have more empathy for their unhoused neighbors, and realize that living outside does not mean you’re a “bad person.”

“I didn’t choose this,” he said. “I’m just trying to survive.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.