PennEast shelves plan to build pipeline on public lands in New Jersey

The company’s decision not to pursue eminent-domain claims on 42 parcels of publicly owned land was announced in an agreement with the Attorney General’s office.

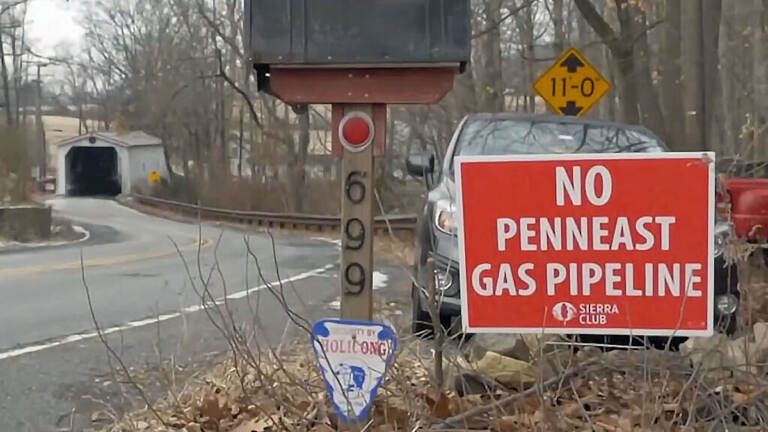

The PennEast pipeline plan has faced strong opposition. (NJ Spotlight News)

This story originally appeared on NJ Spotlight.

PennEast Pipeline Co. has dropped a plan to use New Jersey state lands for its controversial natural gas pipeline — at least for now — dealing a major blow to the long-delayed project in the state.

The company’s decision not to pursue eminent-domain claims on 42 parcels of publicly owned land was announced in an agreement with the Attorney General’s office and recorded in a brief notice sent on Sept. 20 to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, which is overseeing the company’s claims.

“The parties to these consolidated matters have agreed in principle to a stipulated voluntary dismissal of these matters,” the notice said, referring to the eminent-domain claims.

In plain language, the notice means that PennEast won’t seek to seize the lands to build the pipeline, said Leland Moore, a spokesman for the AG’s office, which argued against the company’s use of public lands before the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this year.

The nation’s highest court had sided with PennEast, ruling that it had the right to use eminent domain to acquire the state land it needed for the project.

“We are pleased that after three years of litigation, PennEast has finally paused on trying to take state land,” Moore said in a statement. “Although the company is still pushing ahead with plans to build an unnecessary and ill-conceived pipeline, we will continue to lead the fight against it, and we are confident that we will ultimately prevail in court.”

Company cites timing as an issue

Pat Kornick, a PennEast spokeswoman, would not say whether the agreement means the company has abandoned its plans for the New Jersey section of the pipeline, which has twice been denied state environmental permits, and has roused strong opposition in the communities where it would be built.

“Given the uncertainty on timing to resolve the remaining legal and regulatory hurdles, PennEast believes it is not prudent to complete the acquisition of the rights of way in the pending actions as it might not be necessary for some time,” she said.

Still, Kornick suggested the company is continuing to explore ways of moving the project forward in future.

The company is talking to attorneys about “restarting legal proceedings once it clears the regulatory hurdles and has a better understanding of when it would need to acquire the property interests,” she said.

It was unclear what the regulatory requirements might be, since DEP permits could only be applied for after the lands had been condemned under eminent-domain laws.

Plan at odds with governor’s clean-energy agenda

Neither PennEast nor the AG’s office explained their agreement but opponents said it was probably because the company had accepted the unlikelihood of getting environmental permits given the DEP’s previous denials and the aggressive promotion of clean energy by the administration of Gov. Phil Murphy.

“I think they see the writing on the wall,” said Tom Gilbert, campaign director for the New Jersey Conservation Foundation, and a longtime foe of PennEast. “It’s very clear that this project is not going to get all the necessary approvals. It continues to face numerous significant legal hurdles. It’s clearly at odds with the urgent move towards a clean energy future that’s underway in New Jersey and now increasingly at the federal level.”

Signs of the state’s opposition to the project included its challenge — though unsuccessful — at the U.S. Supreme court earlier this year, and its ongoing appeal against a “certificate of public convenience” issued to PennEast by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Gilbert said.

“It’s pretty clear from the state’s actions that PennEast knows it has numerous significant challenges with the State of New Jersey,” he said. “They have come to the conclusion that it doesn’t make sense for them to press ahead.”

The agreement was also welcomed by U.S. Rep. Tom Malinowski, (D-7th) who called it a “major win for the environment” and for advocates and citizens groups.

120 miles long, with terminus in Mercer

If built, the pipeline would pump natural gas about 120 miles from the Marcellus Shale field in northeastern Pennsylvania, under the Delaware River by Hunterdon County, and finally to a terminal in Mercer County. PennEast has said the pipeline would ensure the continued supply of cheap gas to New Jersey consumers, but opponents have argued the state is already well-supplied with natural gas, and so the pipeline is not needed.

In Pennsylvania, the company in August dropped eminent-domain suits against 70 landowners, saying it was “not prudent” to complete planned acquisitions.

Critics including Gilbert attacked the project’s “self-dealing contracts” which he said are based on its own stakeholders agreeing to buy the gas rather than on a demonstrated public need. He said courts are taking a harder look at pipeline companies’ claims that their projects are actually needed.

The decision not to build the pipeline on public land surprised many observers given the Supreme Court’s ruling less than three months ago that PennEast did indeed have the right to condemn the state lands, reversing an appeals court ruling, and handing a major victory to the company.

“It is surprising,” said Ed Potosnak, executive director of the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters. “They were given the green light, they asked for permission, and then clearly have backed off on that request.”

Potosnak welcomed the company’s decision not to use public lands but argued that it could refile to exercise its eminent-domain rights at any time. “It is not a done deal, no one should be misled by that,” he said.

Jeff Tittel, former director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, predicted it will now be “extremely difficult” for PennEast to find enough private land in New Jersey on which to build the pipeline. He said the company appears to have accepted that it would not get the permits it needed from New Jersey, and perhaps has been worn down by public opposition over the past seven years.

“My sense is that they thought it wasn’t worth the battle,” said Tittel, who opposed the project from the start. “This is important news. It either means they are going to try to reroute it, or it’s going to go away. If you can slow it down, you can eventually stop it. This is one more step towards it not happening.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.