Parkway encampment set to break down tents by the end of the week

Most of the camp’s now approximately 80 occupants will move into city shelters or shared housing until the agreed-upon permanent housing is available.

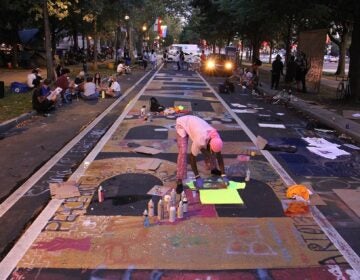

A homeless protest encampment occupies Von Colln Field on the Ben Franklin Parkway on Aug. 20, 2020. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The months-long housing protest and encampment on Benjamin Franklin Parkway will be coming to an end later this week, according to the agreement reached between the camp’s residents and organizers, city officials and the Philadelphia Housing Authority.

On Wednesday, tents had yet to be taken down, and volunteers were still donating food at the James Dean Talib camp on 22nd Street. A small group of men sat around a fire pit as city outreach workers in orange vests arrived to help make plans for the remaining residents. Organizers say the majority of the camp’s now approximately 80 occupants will move into city shelters or shared housing until the agreed-upon permanent housing is available.

One former encampment resident who is now living in a house slated to be handed over to a new nonprofit said she was changed by the experience, and feels some non-residents were as well.

“It was mind-blowing for a lot of people to see people living in tents,” said Patrice, who didn’t want to give her last name. “As a homeless community, we drew people in. We [showed them] we’re not just worthless people, we were helping each other.”

Housing activist Jenn Bennetch, who helped create the encampment, looked around the sprawling site, with its kitchen and medical tent, and said the deal is bittersweet.

“So it’s sad to see this aspect end, but it’s also exciting to be moving forward even though it’s not everything we wanted. It’s a really big start, and it could set a precedent,” she said.

There’s a lot of work ahead to clear the camp and establish the land trust that will serve as a nonprofit affordable-housing provider, Bennetch said. Once that’s established, the city will begin to transfer ownership of 50 properties in a series of phases that includes both federally owned and city-owned houses.

Bennetch has been critical of the federal Philadelphia Housing Authority for years for participating in a program established under the Obama administration known as “Rental Assistance Demonstration,” or RAD. Through RAD, the agency converted some of its rentals into Section 8 housing, the rent subsidy program used by private property owners.

The issue became a stumbling block in the lengthy negotiations between the encampment organizers and city officials. Bennetch’s position was that instead of being sold to developers who could eventually convert them to market-rate housing, the homes should remain as affordable-housing options in perpetuity for the city’s poorest residents.

A number of these RAD houses, which are currently empty, will be transferred to the future land trust, avoiding the issue of having some camp residents jump the queue for affordable housing.

Some of the encampment residents have already moved into these homes, and under a previous deal made with PHA, they can remain.

Bennetch said that after three separate eviction notices issued by the city, a federal court case to try to halt the evictions, and a tense standoff in which barricades were erected, in some ways it has not completely sunk in that, with the deal announced Tuesday night, the encampment organizers prevailed with their main ask.

“Somewhere deep down inside, I was so determined,” she said. “We went from waiting for the cops and having choppers overhead to this.”

Though the Philadelphia Housing Authority coordinates with the city, it is a separate entity that gets almost all its funding from the federal government and provides subsidized housing to city residents.

PHA president and CEO Kelvin Jeremiah said the protest encampments helped elevate the need for affordable housing.

“There’s a desperate need for affordable housing,” Jeremiah said Wednesday. “But the conditions that exist in Philadelphia are not unique to Philadelphia.”

Right now, Jeremiah said, there are not enough resources to address a need that includes 47,000 Philadelphians on a waiting list for subsidized housing.

“For us to meaningfully address the issues, there has to be a meaningful alignment from the city and state as well,” he said. “Ninety-three percent of our funding is from the federal government, but unlike other cities, Philadelphia has not given public housing its fair share.”

As the city’s largest landlord, PHA has about 4,000 scattered site houses throughout the city, and all but about 600 are occupied, according to Jeremiah. He said PHA has raised $20 million by selling off about 600 properties over the past eight years. And that money gets funneled back into desperately needed affordable-housing projects.

This is not the first time a group of unsheltered residents has protested against homelessness and struck a deal with the city. In 1987, housing activists helped residents squat 14 empty homes owned by the city.

That group prevailed in getting then-Mayor Wilson Goode to hand over about 200 houses to a nonprofit. The organization created to fix up and manage those houses, Dignity Housing, exists to this day.

“I think it’s a national model for homelessness activism that people who are ordinarily powerless and voiceless in our political process can join together to win for their cause,” said Dennis Culhane, a professor of social policy at the University of Pennsylvania whose research focuses on homelessness.

“As for the housing, I think almost any housing stock that is added and that is targeted for people who are homeless is a good thing as they too often are at the end of the line,” Culhane said.

The Parkway encampment drew the ire of some neighbors, who said they felt threatened by aggressive panhandling. Logan Square Neighborhood Association president Dennis Boylan welcomed news of the agreement but said the encampment put nearby residents at risk, and he pointed to violent incidents that occurred at the camp, including a stabbing.

Boylan blamed Mayor Jim Kenney for the length of the protest and thought the police should have become more involved.

“This wasn’t Woodstock,” Boylan said. “It was inhumane that the city let this go on for so long. The right thing would have been to shut this down back in June. In the end, they got what they wanted. So why did this drag on? And what was the purpose of going to court?”

As part of the agreement, the city also will use funds from the CARES Act to establish a pilot project with two “tiny house villages.” These are small, single occupancy wooden homes about the size of a bedroom used to house people experiencing homelessness. They share communal kitchen and bath facilities.

A number of camp residents will also be housed through a rent subsidy program known as the Street to Home Rapid Rehousing Pilot Program.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.