‘Paranoia starts to creep in’: Artists describe the pandemic’s emotional toll

The Slought Foundation in Philadelphia put out an open call for artwork reflecting the psychological effects of pandemic life.

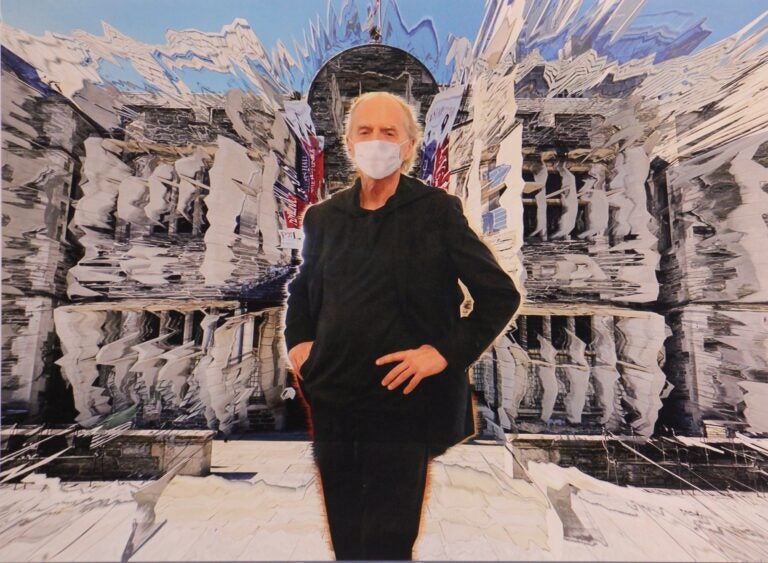

Philadelphia artist Clayton Campbell created two photo montages for Atlas of Affects at the Slought gallery, including this self portrait. (Clayton Campbell)

Clayton Campbell has been careful about how he conducts himself during the pandemic. He works at home in the Fitler Square neighborhood of Philadelphia, and diligently wears a mask if he has to go outside.

But when he sees other people not wearing masks, or wearing them below the nose, or gathering closely, he feels that is a personal affront.

“You have this feeling that everyone you pass, who is not paying attention to the quarantine, is trying to kill you,” said the artist and arts administrator. “That paranoia starts to creep in as you’re just going to the grocery store, doing things you need to do to get through the day.”

Clayton visualized that feeling of being perpetually “frazzled” by the constant threat of contagion in a manipulated photograph, “Self Portrait from Lockdown City.” He submitted it to Atlas of Affects, a project of the Slought Foundation, an organization at the University of Pennsylvania that attempts to spur public dialogue around cultural and sociopolitical change.

Slought’s executive director, Aaron Levy, said the Atlas project was a response to what he saw was a lack of stories in the media about the psychological affects many people experience while sheltering at home.

“We wanted to find a way to capture the emotional lived experience of this historic moment, and make that legible to others,” said Levy. “The Atlas documents affects: personal experiences, joys, loss, anger, shame, denial – experiences we are all having and we’re having them in the confines of our homes.”

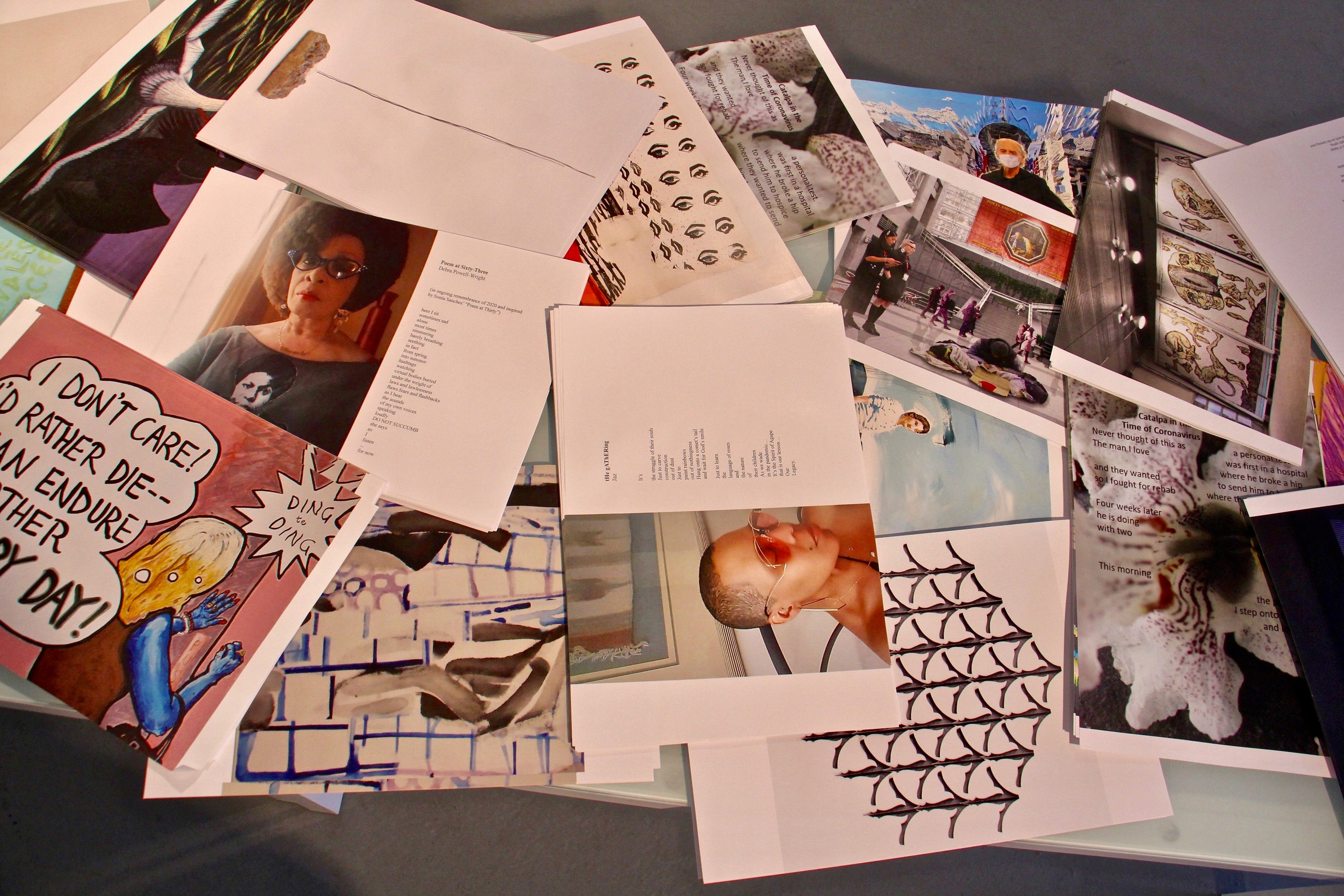

A few months ago, Slought put out a call for submissions of visual and written material that describes the personal toll of living through a pandemic. The Atlas of Affects project received almost 40 submissions from around the world, including paintings, drawings, prints, photography, video, sculpture, poetry, and prose. They are all presented in the Slought Foundation’s gallery at 40th and Walnut streets in West Philadelphia.

A stack of 50 high-quality prints was made of each of the submissions that could be reproduced on paper (excluding video work). Visitors to the gallery are invited to take a print, or several, back to their homes homes or pandemic bubbles. The show cannot be seen online.

The Slought Foundation is treating the artwork as intimate documents of people’s pandemic experiences, with the intention that they should be shared with other people who may also be feeling the affects of living in isolation. By allowing people to bring the works into their homes, Levy hopes the works will be received as intimately as they were produced.

“The very word pandemic derives from the Greek work pandemos, meaning ‘pertaining to all,’” said Levy. “Even though we are isolated, we are all sharing the same experiences but don’t know it.”

One of the pieces that can only be seen in the gallery is a video by Carmen Argote, “Last Light,” in which the filmmaker films herself walking through Los Angeles during the early days of the pandemic, when the streets were eerily empty. The film is currently making the rounds at film festivals, and is not online. A trailer for the short film can be seen here.

Argote looks emaciated. In her voiceover, she explains that she is soon going to the hospital for a medical procedure. During her walks, she recorded herself talking about what she is feeling at that moment.

“I feel like I’m not made to last, like I’m not the one who’s going to make it,” she said in the voiceover, as we watch images of a guard dog barking behind a chain link fence, and emergency vehicles zooming through empty streets.

“Last Light” is a stream-of-consciousness ramble through both geographical and psychological terrain.

“It is a filmed mediation of her walking through her city, while trying to make sense of her experiences in this incredibly strange pandemic,” said Levy. “That idea that an artwork could be a vehicle for a person to therapeutically process what they have lost, really resonated with the ideals of this project.”

Locally, the artist Dolores Poacelli also used her art practice to create a kind of journal of her pandemic experience. The resident of Collingswood, N.J., has maintained an art studio in Philadelphia’s Italian Market for decades, but last spring she temporarily abandoned it.

“I didn’t go to my studio for three and a half months, because my friend there died of COVID,” said Poacelli. “When I went back I didn’t work. I sat in a chair for four hours, and did nothing but think.”

Poacelli normally works with paint and aluminum. When she resumed working, she did it at home, away from the materials, tools and supplies she keeps at the studio. She had to make art from whatever was at hand: recycled paper and black paint.

Using scissors, she hand-cuts black letters and arranges them into abstract shapes that can be read as phrases, describing her feelings about both the virus and politics: “Losing ground in my pursuit of happiness,” “Make boredom possible again,” and “Hope karma gets here before my pizza.”

“I dated each piece, and I soon began to see that I was documenting my personal feelings about a global event,” she said. “I knew I had to call them a diary.”

There are currently 95 pieces in Poacelli’s “Pandemic Diaries.” She is still making them. Having never before engaged much on social media, she now posts new work two or three times a week on Instagram.

“It started with a need to keep busy while I was in the house: If I don’t find a project, this is not going to be good for anybody,” she said. “Doing the obsessive cutting out and designing, it keeps me sane.”

In addition to the Slought Foundation, Poacelli has submitted pieces of her Pandemic Diaries to other institutions collecting material artifacts from the pandemic, including the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the New York Historical Society.

The Slought Foundation is still collecting material for its “Atlas of Affects,” but submissions that arrived after the initial deadline of Sept. 20 may not be included in the exhibition. To submit, email info@sloughtfoundation.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)