These Pa. 17-year-olds are on a mission to make sure their older classmates vote

With the help of a voting nonprofit, a group of 17-year-olds at Benjamin Rush High School is focused on making sure their older classmates vote in the 2022 general election.

Listen 4:41

Nuri Benson is a 12th grade visual arts major at The Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Ask us: As Election Day draws near, what questions do you have?

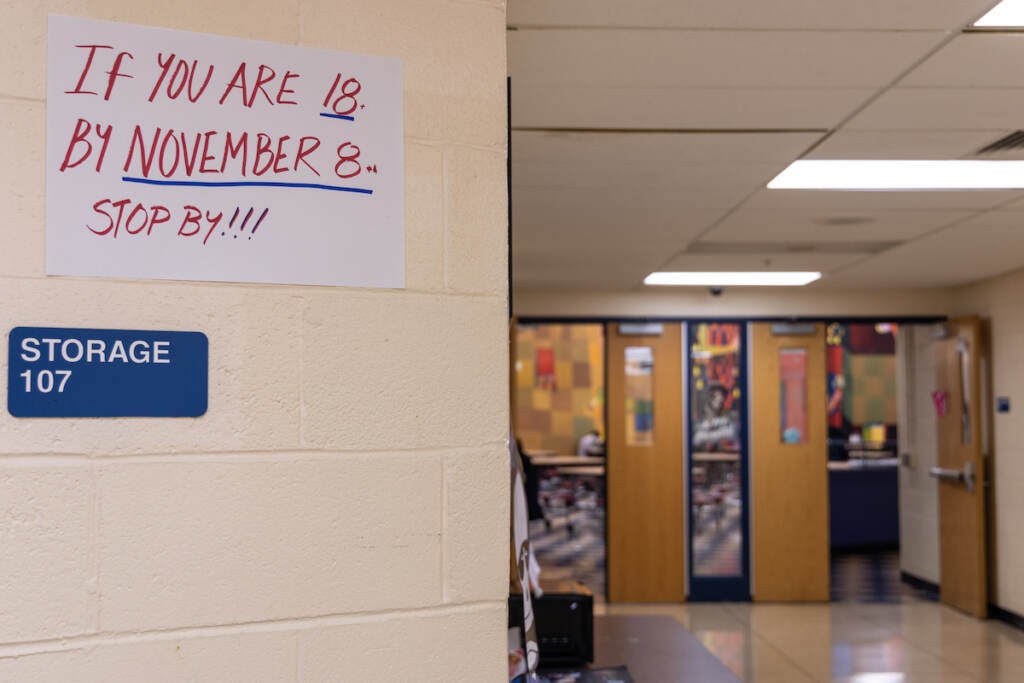

It’s lunchtime at The Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush on a recent Tuesday, and a half dozen students are strategically positioned at a folding table outside the cafeteria.

As their classmates walk past, the students carefully scan the crowd for members of the senior class. When they spot one, the questions come fast.

“Are you 18 years old?” and, if the answer is yes, “Have you registered to vote?”

If a student hasn’t, they offer to help.

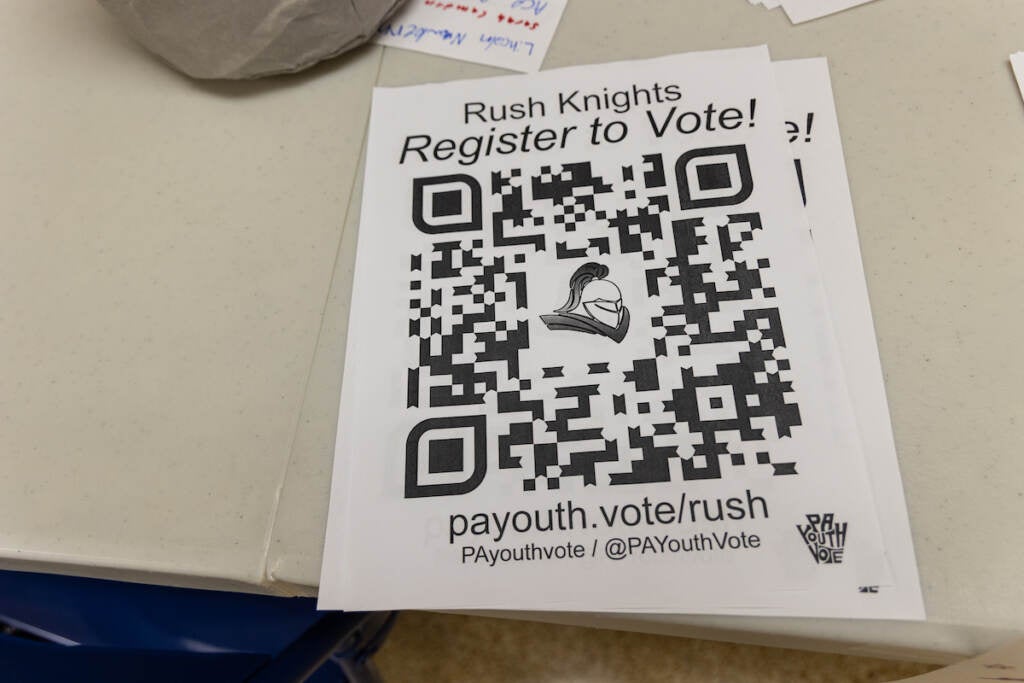

“It’s easy,” promises Andrea Ryan-Costa, showing them an application QR code.

A few minutes later when the registration process is complete, Andrea, 17, adds the student’s name to a handwritten list and presents them with a full-size chocolate bar to celebrate their accomplishment.

“I kind of wish I was registering, but I can’t,” says fellow 17-year-old Ada Pereyra, another member of Rush’s voter registration team.

In fact, at Rush, a magnet high school in Northeast Philadelphia, none of the students on its voter registration team are old enough to vote.

“I want to be a part of this because I can’t vote,” said 17-year-old Bellamena Briglio. “There are problems that have come to light this past year that I feel really passionate about.”

Her biggest concern? The overturn of Roe v. Wade and what that could mean for abortion access in Pennsylvania.

Republican candidates in both the state’s race for governor and its open U.S. Senate seat have promised to severely restrict abortion access. Meanwhile, Democrats have said they’ll preserve abortion access and fight to enshrine Roe v. Wade as the law of the land.

“It’s really upsetting and I can’t do anything about it,” said Bellamena, who is pro-choice.

Anything, except make sure her older classmates vote.

Bellamena doesn’t know where all of her classmates stand on abortion, but she said registering other young people to vote feels better than doing nothing.

Her goal, along with the rest of the team, and their nonpartisan parent organization PA Youth Vote, is ultimately to make sure all eligible students vote.

An offshoot of an earlier Philly-specific group, PA Youth Vote formally launched in 2021 and trains and pays students and teachers to register and educate new voters.

PA Youth Vote provides resources to all of Philadelphia’s public high schools, and is gradually expanding to other districts, according to its leadership. This year, they’re focussed on Montgomery County where they’re working with three new districts.

Where youth registration efforts stand

Students at Benjamin Rush ultimately registered 27 out of 33 of their eligible classmates by the deadline, for a registration rate of 82%.

But when it comes to youth voter registration, Rush is the exception, rather than the rule.

Only about 29% of eligible students in the greater Philadelphia area were registered to vote as of last month, according to the Civics Center.

A week before the state’s registration deadline, only 23.7% of Philadelphia’s 18-year-olds were registered to vote. Registration rates were higher in the suburban counties, with the highest rate in Montgomery County at 37%.

Younger people typically make up a small share of the electorate — around 8% — and are less likely to vote than their parents and grandparents. Only about half of voters 23 years and younger cast ballots in the 2020 presidential election, compared to 75% of the country’s highest-voting cohort, 65- to 74-year-olds.

Recognizing this trend, civic-minded teachers and organizations have pushed to hold registration drives in schools and provide students with the resources they need to make an informed choice on Election Day.

PA Youth Vote Executive Director Angelique Hinton said with limited financial resources and 500 districts in the state, her focus is on serving students in low-income communities of color.

Hinton said these students are less likely to receive civics education due to budget cuts. Not only that, based on personal experience, the students may already feel negatively about politics.

“As they get older, because government never works in their communities, they continue to disengage more and more,” Hinton said.

Last year, she visited a high school in Kensington six times, she said, and ended up with only 10 voter registrations.

“But that felt like a thousand registrations, knowing what that community has seen and the lack of responsiveness that they have seen from government,” Hinton said.

PA Youth Vote tries to combat youth disengagement, which can lead to lifelong apathy, not just by registering teenagers to vote, Hinton said, but by teaching them why voting matters.

For example, a teacher may help students look at how issues they care about, like gun violence, drug addiction, or poverty, are shaped by local policies and by extension politics.

If they want to see change in their communities, the connection becomes clear: Voting is one of the most direct tools they have.

For some teens, voting is ‘scary’

Social studies teacher Rhonda Feder takes her job as Rush’s “Voter Champion” very seriously.

“It turns out that young people don’t often register until someone asks them to register,” she said. “Just the simple process of doing that is pretty powerful.”

Feder said one of the biggest reasons students have for not wanting to vote is that they don’t feel ready.

“I feel like [young people] are a little hesitant to step into it and I totally understand that because I’m also hesitant,” said 18-year-old Rush student Olivia Chen minutes after she registered to vote during her lunch period.

Olivia said with the divisiveness of politics in America, she liked being apolitical.

But like her classmate Bellamena and so many other young women, Olivia said the overturn of Roe v. Wade complicated her feelings. Now, she feels like she has to vote.

“It’s gonna be so awkward,” she said, thinking about Election Day. “I’m probably not going to have any idea what to do. I’m probably going to stand there lost like, ‘What do I do? Help!’

“It’s just the sense that maybe they’ll know I’m freshly 18,” she said with a laugh.

To combat this, Feder planned to meet with students before Election Day to teach them about the candidates and go over the basics, like how to locate their polling place, use a voting machine, and read a ballot.

“That way when they go to vote, it’s not a mystery or a big, scary process,” she said.

Other challenges teens face in voting

There are also other challenges to voting that specific students face, Feder said.

For example, if a student is transgender and hasn’t legally changed their name, they have to register with their dead name. The form also requires students to pick a gendered title, leaving no option for students who are nonbinary.

Another obstacle can be a student’s family, Feder said. If the political climate in their household is contentious, voting may be something they want to avoid.

While the work Feder does is strictly nonpartisan, she said she’s had to do more in recent years to counteract partisan misinformation.

“There are always students who will say my vote doesn’t matter, one vote doesn’t matter. There’s corruption. There’s fraud,” Feder said.

She relies on history to keep them motivated. She teaches students in her civics class about voting reforms including the move to a secret ballot in the 1890s. They also study the centuries-long struggle for voting rights.

Feder explains to students that almost no one in the room would have been allowed to vote when the country was founded and that “people fought really hard and died” to expand suffrage.

“That’s less persuasive with young people than I would think it should be, but it does speak to some,” she said.

Fortunately, for Feder — and for democracy — having a say often does feel powerful to the students.

“That’s usually motivating.”

What issues do students care about?

The issues students at Rush said they care most about range from criminal justice reform to the need for more sex education in schools.

Andrea Ryan-Costa said she’d like to see more policies that prevent young people from using drugs.

“I know 12-year-olds who are smoking weed and that’s cool for you, I guess, but it leads to so many other things,” she said.

Her friend, 17-year-old Janiya Jenkins, agreed but cautioned against incarceration.

She said she sees rehab and restorative justice as a better solution.

“I would love to see more people talk about that instead of just a hard takedown on drugs because it’s more than just the drugs themselves,” Janiya said.

Another big issue for students in Rush’s voter registration group is abortion.

While not all of the girls shared where they fall on the issue, and whether it was the reason they’d been, in voter engagement terms, “activated,” they all agreed a more nuanced conversation is needed.

“I hope that schools start teaching things about abortion because when you hear about abortion you hear pro-choice or pro-life but not, like, the fundamentals of abortion,” said 17-year-old Nuri Benson.

Nuri thinks the history of abortion should be part of the conversation, she said, as well as how the U.S. arrived at the current political moment, one that in her description is rife with misinformation that fuels polarization.

“I hope people get educated on it so people can form their own ideas about abortion,” he said.

Regardless of whether schools take up the topic of abortion, Bellamena said, students need more and better sex education.

“Why not just teach safe sex?” she said. “I know myself and so many other females, they don’t even really know what’s going on with their bodies.”

At Rush, sex education is limited to junior year. And while there are free condoms in the nurse’s office, that isn’t enough to create a sex-positive atmosphere, students said.

Students said they think comprehensive sex education should start in middle school and that information on safe sex should be abundant.

“It should be something that’s well known in the space of the school,” Janiya said.

Andrea said when it comes to seemingly “taboo” topics like sex and drugs, it’s always better to give teenagers more information, not less.

“They know that we’re going to do it, but they don’t want to educate us on it,” Andrea said. “When people feel that they can’t talk about something they come to their own conclusions.”

As members of Rush’s voter registration bounced policy ideas off of one another, Janiya shared a smile with another member across the table.

“I look forward to when we’re really old so we can be politicians,” she said. “Now, that’s going to be interesting.”

Your go-to election coverage

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.