A trailblazing Black, female composer’s work is revived by Opera Philadelphia

A major work by an undersung Black, female composer from the 1960s, based on the writings of W.E.B. DuBois, is being staged at the Academy of Music

Listen 2:22

Composer Margaret Bonds (Courtesy of Opera Philadelphia)

Florence Price has been having a moment in Philadelphia, thanks in large part to the Philadelphia Orchestra’s recent performances and recordings of the historically undersung compositions by the pioneering Black woman composer who died in 1953.

Now, Price is sharing the limelight with another Black woman composer: Margaret Bonds.

Opera Philadelphia is launching “Sounds of America: Price and Bonds,” a two-year initiative to highlight the work of both composers and their circle of colleagues, which includes figures like Langston Hughes and Marion Anderson.

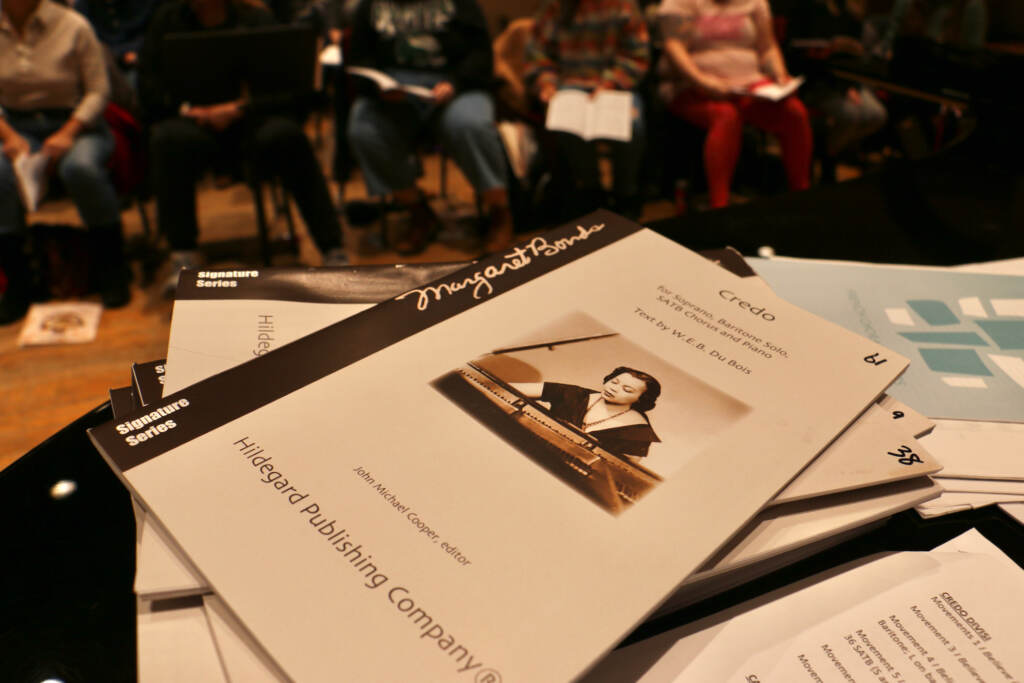

This weekend the Opera will perform “Credo,” one of the final works written by Bonds before she died in 1972 at age 59. The work capped a successful and prolific career for the pianist and composer.

“It is a piece of music that — not only through the text but also through the musical language — tells a story that has unfortunately not been heard on a regular basis within the traditional concert hall,” said Veronica Chapman-Smith, vice president of community initiatives. “We want to be a part of a movement helping to bring light to beautiful pieces of work that are telling a story that unfortunately did not get the light of day at the time they were written.”

“Credo” is based on a prose poem by W.E.B. DuBois published in 1904, in which the writer lays out nine points of personal belief towards racial equality: God, “the Negro Race,” pride, service, the devil, “the Prince of Peace,” liberty for all men, the training of children, and patience.

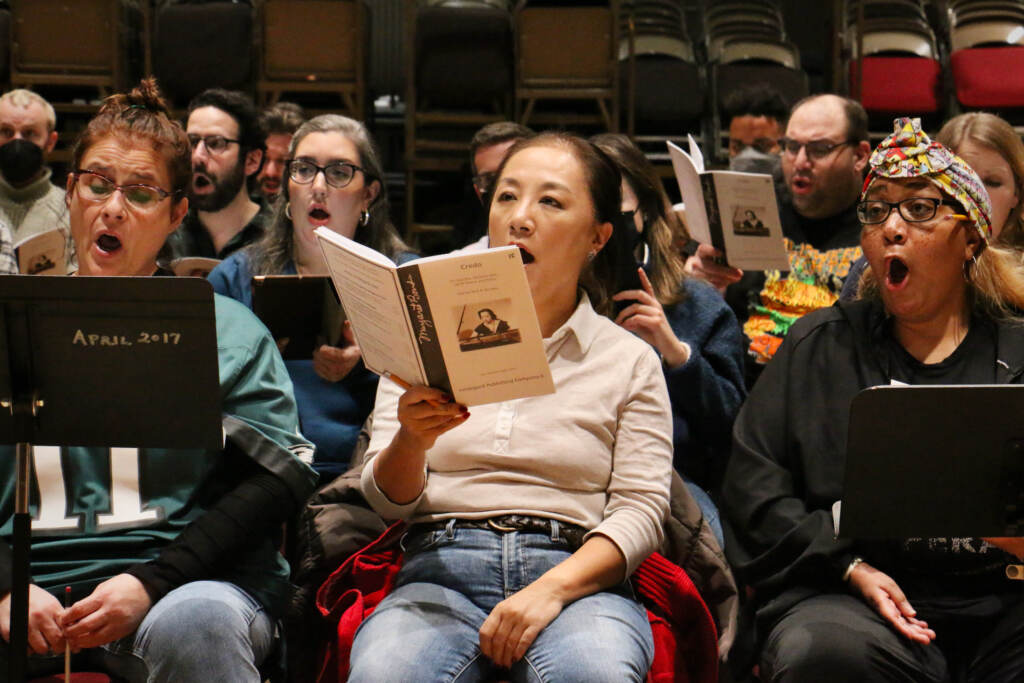

Bonds set seven of Dubois’ points to music as the seven movements of “Credo.” It will be performed with a full, 80-voice chorus and orchestra, on a program with audience favorite “Carmina Burana” by Carl Orff.

“It is based on the structure of a Latin mass,” said Chapman-Smith, who is also an opera singer and will be in the “Credo” chorus as a soprano. “It’s based on that, but instead of going down what might be seen as a religious path, DuBois goes on a different path.”

Margaret Bonds was born in 1913 to parents who were central figures in the civil rights movements in Chicago. Her father was physician Monroe Alpheus Majors, who wrote an anthology of historical Black women, “Noted Negro Women: Their Triumphs and Activities,” in 1893. Her mother was Estelle Bonds, a church musician and member of the National Association of Negro Musicians.

When Bonds was very young her parents divorced. She took her mother’s name and lived in her house, which was often visited by major Black musicians of the day, including Florence Price.

Rollo Dilworth, a composer and conductor who is the vice dean at Temple University’s Center for the Performing and Cinematic Arts, developed educational material for Opera Philadelphia and its Sounds of America program. He said Bonds started writing songs at age five, and would later study under Price.

“She was really committed to fusing her identity as an African-American woman with the European classical training that she was receiving. In essence, creating a new genre,” Dilworth said. “Both she and Florence Price were very committed to that.”

Bonds studied music at Northwestern University, where she graduated with both Bachelor and Masters degrees at age 21. But as one of the very few Black students at the university, she encountered a degree of hostility and racial prejudice that she found nearly unbearable.

In the university library she stumbled upon a book of poems by Langston Hughes, in which Bonds found great solace, in particular Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

“That poem helped save me,” she later wrote.

Not only would Bonds set “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” to music, but she collaborated directly with Hughes on several musical projects before his death in 1967.

“She began to find resonance with social justice themes through the writings of Langston Hughes,” Dilworth said. “Shortly after the passing of Langston Hughes, Margaret wanted to continue her work in that vein.”

Bonds wrote a cantata dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr., “Montgomery Variations” (1964), and then in 1968 took up the writings of DuBois.

“This was the late 1960s, at the pinnacle of the Civil Rights Movement. She wanted to use her artistic platform to make a statement, to speak out in the name of social justice and social change,” Dilworth said. “She was probably one of the first classical composers to really do this kind of work.”

“Credo” is structured in a European classical tradition, with motifs echoing in patterns across the movements. Bonds also included musical phrases referencing traditional spirituals and jazz.

“Credo.” (Emma Lee/WHYY)

“Her music is lush and full. It has many phrases that sound a little jazzy and that speak to me in a different way than I hear in traditional Eurocentric music,” said Chapman-Smith. “That kind of jazzy-ness goes like, ‘Ooh! That’s an American sound!’ I like that.”

“Credo” was one of Bonds final compositions. She had a busy and successful career, with one of her works even televised: In 1960, CBS broadcast a performance of her Christmas cantata “The Ballad of the Brown King.” But after her death in 1972, Bonds’s legacy, just as that of her mentor Florence Price, did not enter the American musical mainstream.

“I think their contributions to classical music have gotten lost,” Dilworth said. “Now that we’re in 2023, there seems to be a lot of attention being paid to female composers in particular, but also composers of color. Florence Price and Margaret Bonds are certainly some of those trailblazing figures.”

Opera Philadelphia’s ongoing Sounds of America initiative will include events, concerts, and educational material spotlighting Bonds, Price, Marian Anderson (for whom Bonds wrote material), and the extensive network of Black and female musicians they worked with.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.