New Jersey still a long way from recovery, report shows

The jump in New Jersey’s unemployment rate last month to 9.6 percent — the farthest the state has been above the national average in 30 years — is just the latest in a series of sobering statistics on the state’s economy and budget.

The 0.4 percent increase from May’s unemployment rate put New Jersey 1.4 percent higher than the national average of 8.2 percent, although the bad news was offset somewhat by a gain of 9,900 jobs during the month.

But more troubling news came out of the State Budget Crisis Task Force report issued last week by a blue-ribbon panel of economists.

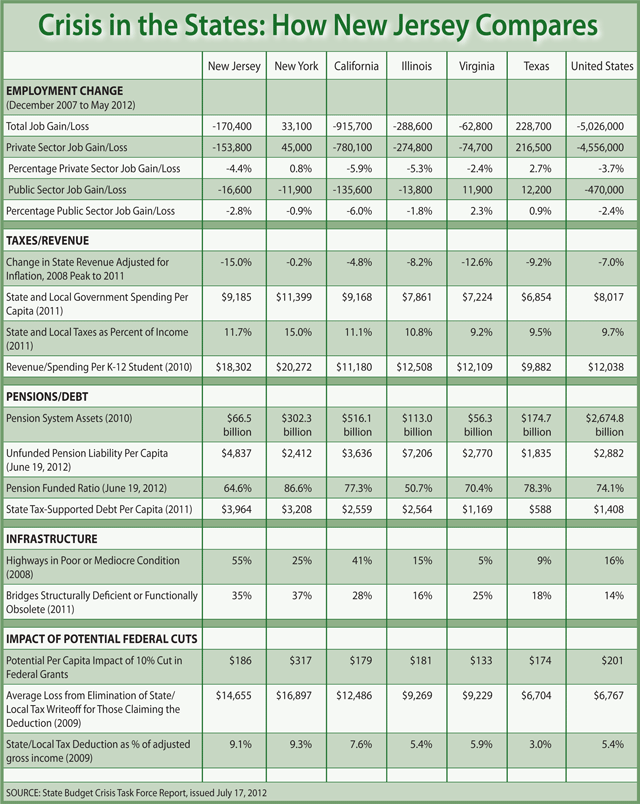

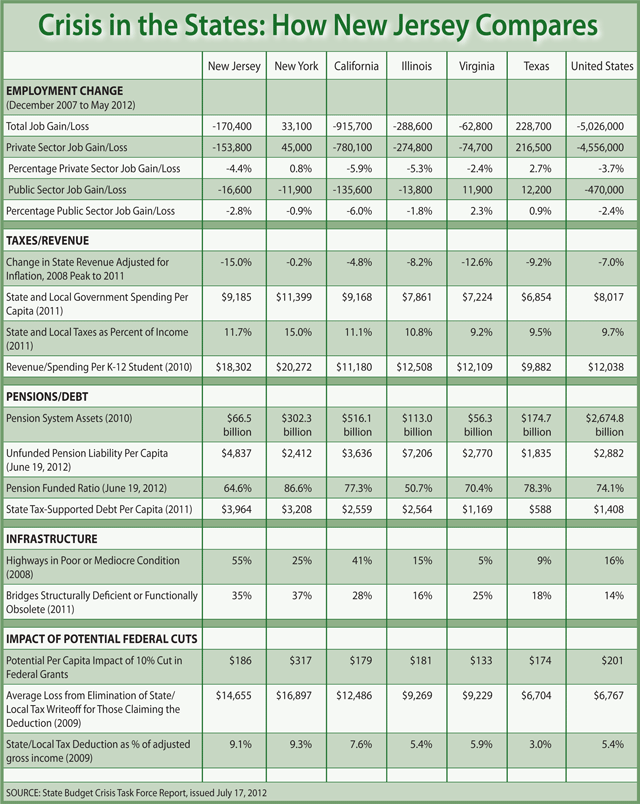

View a breakdown of the State Budget Task Force report

It warned that New Jersey and other state governments faced looming fiscal crises in the years ahead that will require new revenues or draconian cuts.

No economic or fiscal report can be issued over the next year without raising questions about Gov. Chris Christie’s “New Jersey Comeback” and the ongoing debate between Christie and Democratic legislative leaders over whether the state can afford an immediate income tax cut. Christie’s Treasury spokesman, Andrew Pratt, immediately asserted that the state’s problems were “decades in the making” and contended that Christie’s policies had “pulled New Jersey back from the fiscal cliff.”

Indeed, study co-chairs Paul Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, and Richard Ravitch, a former New York lieutenant governor, praised the pension bill pushed through by Christie and Senate President Stephen Sweeney (D-Gloucester) last year as a positive step, as did former Office of Management and Budget chief Richard Keevey, who also served on the task force.

But Volcker and Ravitch predicted that New Jersey and the other state governments studied will be running into severe fiscal shoals in the years ahead, and Keevey specifically warned in a WHYY interview that New Jersey’s fiscal problems are so deep that “we’re on a track that the revenues will not match with the expenditures in the long run.”

The report

Indeed, of the six large states included in the State Budget Crisis Task Force Study — New Jersey, New York, California, Illinois, Virginia, and Texas — New Jersey arguably faces the toughest overall road:

Even with the new pension law, New Jersey’s combined unfunded pension liability and outstanding state debt equals $8,801 per person, second only to Illinois’ $9,770, and more than double the national average of $4,290.

New Jersey state revenue in Fiscal Year 2011 — the last year for which revenue figures are available — was 15 percent below its FY2008 pre-recession high, more than twice the national average of 7.0 percent, worse than the other five large states in the study, and sharply below New York State, whose revenue was down just 0.2 percent.

As of May, the total number of jobs in New Jersey was still 170,400 below the number of state residents working when the Great Recession hit in December 2007 — better on a percentage-loss basis than California and Illinois, but in sharp contrast to New York State, which has not only regained all of the jobs lost, but added 33,100 new jobs in the same period.

Fifty-five percent of New Jersey’s highways were in poor or mediocre condition — more than twice as high as in neighboring New York, 3.5 times the national average of 16 percent, and worst among the six states studied.

Thirty five percent of New Jersey’s bridges were structurally deficient or functionally obsolete, ranking second to New York State’s 37 percent and 2.5 times the national average of 14 percent.

Keevey warned that New Jersey revenue growth in the years ahead would not be sufficient to simultaneously fund the rise in pension contributions required by the new pension law; the cost of needed repairs to highways, bridges, and other infrastructure; the increasing cost of Medicaid nursing home care for an aging population; school aid, debt service, and other growing costs.

In that regard, the State Budget Crisis Task Force report echoed the 2011 and 2012 “Facing Our Future” reports written by Keevey and a bipartisan panel of former high-ranking state officials under the aegis of the non-profit Council of New Jersey Grantmakers.

Comparing New Jersey to other states

What made the State Budget Crisis Task Force study different was that it benchmarked New Jersey against five other states that together make up more than 35 percent of the nation’s population, and it showed that, in comparison, New Jersey’s long-term problems tend to be deeper and that its overall recovery from the job and revenue losses of the Great Recession of 2007-2009 has been slower.

New Jersey and Illinois were on an equally poor pension footing before the state’s new pension law froze cost-of-living adjustments for retirees, required current employees to contribute more toward their pensions, and forced the state to phase in pension contributions over a seven-year period that will bring the state to full funding — and the pension system’s funded ratio to 80 percent — by Fiscal Year 2018.

However, as the study showed, New Jersey’s state tax-supported debt amounts to $3,964 per person — $756 more per person than New York, which had the second-highest debt of the six states studied, and almost seven times as much as Texas, whose state debt per taxpayer is just $588 per person. Further, New Jersey’s debt will keep rising because most of the state’s $1.6 billion-a-year Transportation Trust Fund is being borrowed over the next four years, and a new higher education bond issue is on the ballot this fall.

The study showed that New York has done better than New Jersey, California, Illinois, Virginia, and the nation as a whole in recovering the jobs and tax revenue that were lost during the recession. This has occurred even though New York’s state and local governments were spending $11,399 per person, which represented 15.0 percent of personal income. Both spending figures were more than 25 percent higher than the second- and third-ranked states — New Jersey, whose $9,185 in state and local government spending represented 11.7 percent of income, and California, whose $9,168 in spending ate up 11.1 percent of income.

New York’s net cut of 11,900 government jobs since the recession began represented just 0.9 percent of public sector jobs, compared to a 16,600 reduction that equaled 2.8 percent of New Jersey’s public sector workforce.

California’s severe state and local budget crisis resulted in a net loss of 135,600 government jobs equaling 6.0 percent of the public sector workforce, while, Texas, under conservative Republican Gov. Rick Perry, and Virginia have actually added 12,200 and 11,900 government jobs respectively since the recession.

California’s net private sector loss of 780,100 jobs and Illinois’ private sector drop of 274,800 jobs are both higher on a percentage basis than New Jersey’s net loss of 174,100 jobs (which would actually result in just over 164,000 with June’s job gains added in).

The two states at the opposite ends of the tax spectrum were the only ones among the six studied to gain private sector jobs, with Texas’ addition of 216,500 private sector jobs representing three times the percentage gain of New York, whose private sector employment is up 45,000 since the recession. Overall, national private sector employment remained 4,556,000 — or 3.7 percent — below the December 2007 start of the recession.

With President Obama and the Republican-controlled U.S. House of Representatives still wrangling over federal budget cuts, the State Budget Crisis Task Force report also assessed the impact of potential federal cuts on the states.

New York would be hit the hardest by a 10 percent across-the-board reduction in federal aid, losing $317 per person. The other five large states studied would all come in below the $201 per capita national average. New Jersey’s $186 loss per person would rank second among the six, followed closely by Illinois at $181, California at $179, and Texas at $174.

However, New York, New Jersey, and California would be severely hurt by any federal deficit reduction plan that eliminated the federal tax deduction on state and local taxes paid.

Based on 2009 figures, New Yorkers would lose an average of $16,897 representing 9.3 percent of adjusted gross income for those claiming the deduction on their federal tax returns, and New Jersey would not be far behind with a $14,655 deduction loss representing 9.1 percent of adjusted gross income. California’s $12,486 deduction loss would represent 7.6 percent of adjusted income, and Illinois at $9,269 and Virginia at $9,229 would also come in well above the national average of $6,767.

“New York, New Jersey and California appear to be most at risk if the deduction for state and local taxes is scaled back,” the State Budget Crisis Task Force report noted.

“The effective “tax cost” of state and local government services to residents of those jurisdictions would rise, placing downward pressure on state and local spending and taxes and increasing incentives for individuals and businesses to move to lower-tax locations,” the study concluded.

Furthermore, the overreliance on one-shot, nonrecurring revenues by New Jersey and the other states studied would limit the ability of states to cope with such a cut, the study said.

The graphic below shows how New Jersey compares with other states in employment change, taxes and revenue, pensions and debit, infrastructure and impact of potential federal cuts. The information used in the graphic is from the State Budget Crisis Task Force Report, issued July 17, 2012. (Graphic courtesy of NJSpotlight.com)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.