‘My mind’s made up’: Trusted vaccine messengers in Camden have their work cut out for them

An effort to get Camden barbers to act as trusted messengers for the COVID-19 vaccine shows how hard fighting misinformation really is.

Listen 4:51

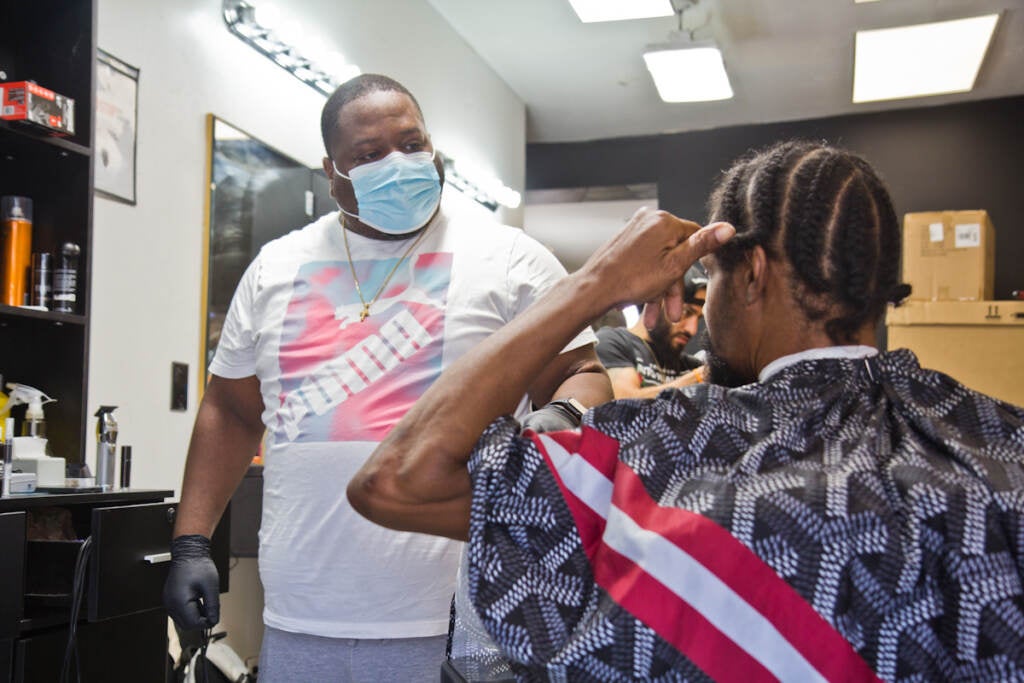

Javan Rankines, a barber and the owner of a cleaning business in Camden, N.J., was recruited to spread the word about the COVID-19 vaccine to his customers. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

Visit the Essential Blends Hair Studio in Camden on any given day and you’ll find a bustling barber shop humming with music and chatter about daily life. Bring up the COVID-19 vaccine and the room will suddenly go quiet, save the buzzing of hair clippers.

“Even though I might not be able to convince somebody, they can understand why I take the position that I take,” said Javan Rankines, after his pro-vaccine talk dampened the mood at the shop last Thursday.

Rankines is one of 15 Camden barbers recruited by the Center for Family Services, a local nonprofit, and Rutgers University-Camden to act as a trusted messenger. The thinking goes: Someone like Rankines is more likely to convince his neighbor or customer who is on the fence about the vaccine than an incentive, which new data finds weren’t as effective at boosting vaccinations as once thought.

Still, Rankines is not sure how many people he’s managed to convince. He can’t even sway some of the people closest to him, including his coworker Donald Smith.

Smith, who is Black, has a list of widely quoted concerns: The vaccine was rolled out too quickly; you can still get sick even if you’re fully vaccinated (though breakthrough cases are rare and you are less likely to get seriously ill); no vaccine is FDA-approved (except for emergency use); and the medical community has a history of neglecting and taking advantage of Black communities.

But then his concerns take a conspiratorial turn. Smith said he’s heard the vaccine makes you infertile, though there is no evidence supporting this claim. Smith said he read injection sites were magnetized; the vaccines cannot make our bodies magnetic. Finally, Smith pointed to a widely debunked story about soldiers in Australia forcefully vaccinating people, including children. Though false, the story gained traction after conservative commentator Candace Owens reiterated the inaccurate claim on Instagram in July. It reinforces his belief that governments and pharmaceutical companies don’t have his best interests at heart.

“I do my research and continue my research and it’s showing there’s more cons than pros and my mind’s made up,” said Smith. “It would take several years for me to say, all right, these people have been vaccinated and their offspring, … those kids come out perfectly fine, they seem like they’re fine, those people live a long, healthy life. Then I’d say, you know, I might get vaccinated.”

Rankines is trying these conversations as the delta variant becomes a greater concern across the United States, with state and municipal governments opting to bring back mitigation efforts like indoor mask mandates.

In New Jersey, Camden officials have slowly boosted vaccination efforts by promoting state incentives and using other outreach methods. Just last week, Mayor Vic Carstarphen walked through city neighborhoods, promoting the vaccine on a bullhorn.

The city lagged behind the rest of the state in the early months of the vaccine rollout. At the moment, the city has delivered at least one shot to 60% of adults over 18. That number stood at 55% a month ago.

Megan Lepore, with the Center for Family Services, said the need to educate adults on the vaccine is more important than ever as children return to school and find themselves more vulnerable to the delta variant.

Children over 12 are already eligible for the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine.

“If we’re not already preparing adults to make the right decisions for themselves, how can we think that they are going to be armed with the right information to make that decision for their kids?” said Lepore.

But for many people like Smith, testimonials he’s found on social media of people who claim they’ve had adverse side effects are more powerful than a fact-checked story disproving a myth he found online.

“We still see people that pass away that aren’t spoken about,” he insists, as other people in the barber shop nodded in agreement. “It’s not on CNN. They don’t publicize because it’s bad for the press. It’s bad for Big Pharma. It’s bad for the health industry, period.”

At the end of the day, Smith is more afraid of what could happen if he does get vaccinated than what could happen if he doesn’t.

“I have a family that cares about me. I care about them. I have children, I have to live on,” he said.

Here is where experts like David Rapp — he helped write a handbook on how to “improve vaccine communication and fight disinformation” — see an opening to have some fruitful conversations.

Despite a flood of PSAs from celebrities and politicians, the Northwestern University professor of psychology and learning sciences finds it unlikely any single high-profile person or organization will be able to convince someone who is on the fence. So he thinks the one-on-one, trusted messenger work is still the best avenue to win people over, though Rapp admits it can be a lot to ask of people.

Still, misinformation can plant the seeds of doubt for people on the fence or reinforce core beliefs that are often tied with people’s identity, such as thinking the government does not have a community’s best interests at heart.

“If someone really believes the medical community doesn’t have people’s best interests at heart, there could be real reasons that they hold, and their own experiences that have suggested that’s the case,”explained Rapp. “It might be part of who they think they are to say ‘I’m going to fight against or reject the medical community’s visions for how people should behave.’”

To scoff at someone who is holding out on the vaccine and repeating disproven stories will only put them on the defensive, he said.

“To effect change, really encourage people to take up vaccination behaviors, we have to meet them where they’re at,” argued Rapp. “And then think about what are the core issues that are making them resistant to … get vaccinated.”

Lepore said that’s what the barber program is meant to do. It took three months to reach the 15 barbers in the program — that’s three months of outreach workers making in-person visits, getting peppered with questions, and coming back with answers.

“You have to walk back over a year-and-a-half of misinformation about this,” said Lepore. “I know it sounds like 15 people isn’t a high number, but again, that’s why it took so, so long to get some of those 15 people. It was conversations. It was weeks and weeks and weeks of conversation.”

That’s how Rankines was won over. He learned he was more at risk of getting serious coronavirus complications because of his weight and outreach workers helped him find a vaccination clinic. Family also helped sway him.

“It was like, I got to do what I need to do in order to enjoy the summer and also enjoy family and friends,” said Rankines.

Rankines tells his childhood friend Anthony O’Neal he had no side effects after getting his jab.

“I’m actually proud of him having the vaccination, but I’m actually scared for him too,” said O’Neal once he was out of Rankines’ barber chair.

Like Smith, O’Neal is taking a wait-and-see approach, opting to socially distance instead, despite being one of the last holdouts in his family. When Rankines politely broached vaccination talk, something he said he does on a case-by-case basis, O’Neal politely listened and almost appeared like he was being won over, until he wasn’t.

Rankines said this is what makes it hard to know how many people, if any, he’s convinced. But he remains optimistic.

“Even if I can reach one out of ten, that’s good,” he said. “You’re not going to reach everybody.”

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)