Long ignored, private online schools see golden opportunity in pandemic

Cyber charters get the most attention, but there’s a niche world of private online academies. Could they be having a moment?

Listen 5:03

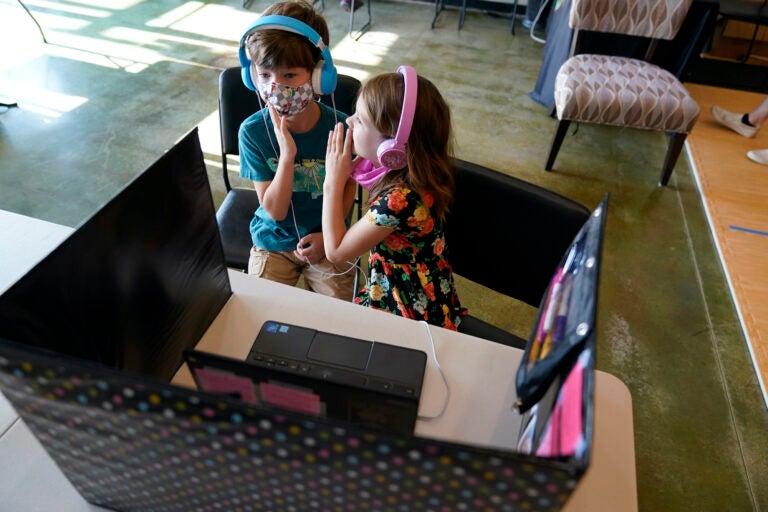

In this file photo, Audra Quisenberry, left, and Logan Bowhay, both 6, wait to meet other schoolmates via Zoom on Monday, Aug. 24, 2020, in Wildwood, Mo. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

As she entered her senior year this fall, Kayla Shenk felt ready for a change.

She adored the small Quaker school she’d attended since 6th grade. But because of its size, the school didn’t offer all of the advanced science courses she wanted to take as she prepared for college.

And with the coronavirus pandemic still smoldering, she and her mom, Patti, figured she’d be better off at an online school that could offer a big course catalog and grant Kayla some of the independence she craved.

“School’s gonna be kind of messed up this year,” said Patti Shenk, who lives with her family just outside Reading. “Why don’t we consider it? Why not? We have nothing to lose.”

A Google search led them to a place called Laurel Springs School, a virtual private school with tuition starting around $6,000 for a full year of high school courses, although tuition varies based on each student’s grade level and course selection.

Laurel Springs is widely regarded as the nation’s first virtual school, with roots dating back to the early 1990s, when the internet was in its infancy. One of its two physical headquarters is in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

If you haven’t heard of Laurel Springs, you’re probably not alone. Historically, it hasn’t served the average student.

“Many of our students come to us for flexibility,” said head of school Megan O’Reilly Palevich. “They’re athletes. They’re actors.”

Only a sliver of kids needs a school that fits around intense training, working, or travel schedules.

Kayla Shenk isn’t one of them. But she wound up at Laurel Springs anyway, which is what excites Palevich. Suddenly, it seems, her niche school is serving a different kind of family.

Enrollment at the 6,000-student school has nearly doubled over the past year, she said.

“The profile that I’m seeing now are parents who have students in public schools, in private schools, in Catholic schools who are just not satisfied with what that school is providing for them online,” said Palevich.

A black box

Few conversations surrounding virtual education revolve around private schools.

Most of the attention drifts to cyber charter schools, which are publicly funded and privately run. Thanks to a pandemic-inspired boost, there are now about 60,000 Pennsylvania students in the state’s cyber charter schools.

Research generally suggests students don’t perform well in cyber charter schools, and they’ve long earned the ire of the public school districts because those districts must pay a fee every time one of their students enrolls in a cyber charter. But proponents say they’re a necessary alternative for students who struggle in traditional settings.

How good are private online schools?

Your guess is as good as the experts’.

“I’ve never seen a single research study that looks at student performance or completion or retention or anything like that that focuses on private online schools,” said Michael Barbour, an expert on virtual education at Touro University California.

No one even knows how many American students attend private virtual schools. Barbour estimates it’s around 100,000 or 200,000, but he admits it’s a dartboard-throw of a guess. Furthermore, many homeschool students buy online courses a la carte from companies that charge a per-class fee for virtual content, which makes those students hard to count.

It is an undoubtedly small universe of students. But entrepreneurs and practitioners see a massive opportunity for growth.

“The reason parents didn’t jump before is because [traditional] school is what they knew,” said Jessica Parnell, who runs Bridgeway Academy, a company based near Allentown that offers online courses to about 10,000 homeschool parents across the country. “That has shifted — absolutely changed. Parents are starting to realize that home education doesn’t mean filling six to seven hours a day.”

Maximum independence

Private virtual schools say they can offer something even cyber charters cannot — maximum independence and flexibility.

Many cyber charter schools require students to log in every day or take a certain number of synchronous classes where students and teachers interact in real-time.

Laurel Springs has no such requirements. Classes are asynchronous, meaning students can complete them at their own pace. They can even start and end the school year whenever they want.

Kayla Shenk, the Laurel Springs senior, often works a bit in the morning, takes a mid-day break, and then revisits her studies around 6 p.m. She’s already finished one of her classes this semester, and she gave herself a week off around Christmas by plowing through assignments the weekend before.

“When I wanna do work and I’m just bored and really want something to do then I do some more work,” said Kayla. “It really depends on my mood.”

She admits that she’s a self-starter — unusually mature for her age. But the world of unusually mature students is larger than the world of child actors. It’s an emerging target demographic for schools like Laurel Springs, one that could nudge them from the educational fringe toward something that resembles a mainstream alternative.

“I really think we are at this tipping point of education,” said Palevich.

The future of school…and work?

One reason for Palevich’s enthusiasm has nothing to do with the recent disruptions to public education. It has to do with the disruptions to the world of work.

Many families could never have entertained a model as freewheeling as Laurel Springs because they needed some physical place to take their kids during the day while they work. Now, parents are getting a taste of what it’s like to work a flexible schedule from home. And they’re getting a taste of what it might be like to have a more present role in their kids’ education.

Palevich notes that enrollment in Laurel Springs’ elementary grades has nearly tripled. Parnell says Bridgeway Academy has also seen its largest growth in younger students.

Fusion Academy, a nationwide network of private schools that offers one-to-one instruction for students, recently launched a fully virtual online academy. It believes its scale allows it to offer course options that simply aren’t available to most students.

“We have 60 campuses across the country,” said Kristen Coyne, head of school for Fusion’s campus in Malvern, Pennsylvania. “If our campus doesn’t have a teacher that teaches Mandarin, but maybe a Los Angeles campus does, those teachers have been able to help our kids that want to take that Mandarin class.”

These schools hope their personalized education pitch will appeal to families that might have relied on traditional schools before, but now have the flexibility to supervise their kids during the day.

It’s a cultural shift online schools are watching closely. What if after the pandemic millions of parents suddenly have the freedom to work remotely?

“You could go travel or go vacation or move out of the city or work at the beach or whatever,” said Palevich. “Your child can take school with them just as you can take work with you.”

Sound like a fantasy? A nightmare?

That’s likely in the eye of the beholder.

Barbour believes most parents will be eager to get their kids back in a traditional school once the pandemic ebbs. Working from home while supervising school work has been an unholy strain on many families.

“They’re gonna slingshot [back] to what they’ve always done,” said Barbour.

That said, millions of families are being exposed to the dual worlds of remote schooling and work right now. If even a small percentage find that setup appealing and want to stick with it long term, their migration to online schools could transform this long-ignored corner of the education world.

“This is the disruption they were waiting for,” said Barbour.

Get more Pennsylvania stories that matter

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)