Kensington residents to speak out about journalist voyeurs in their neighborhood

The Philadelphia neighborhood has been in the national media as the epicenter of the opioid crisis. An online forum will let residents sound off about how their story is told.

Listen 2:07

Volunteers brought a broom and cleaning supplies to clear debris left in Kensington. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The Kensington neighborhood of North Philadelphia has been in the spotlight of major news outlets for several years, and not in a good way.

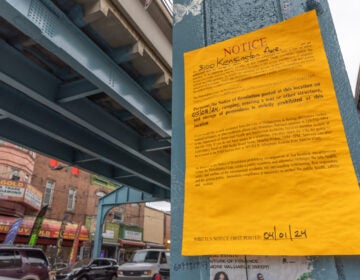

Local and national journalists armed with cameras descended on the homeless encampments and beneath overpasses where widespread opioid use was rampant, taking pictures of anything they could find.

Community activist Gloria Cartagena said none of that media attention was good.

“I live right on Kensington and Somerset. I see everything, but I’ve never seen a journalist stop me to talk about something good,” Cartagena said. “They just snap, snap, snap, snap.”

Cartagena recalls seeing two men with cameras walking down Kensington Avenue wearing bullet proof vests. She watched them take pictures of people using drugs on the street, and laughing about it.

She approached them to find out what they were doing.

“They were trying to start some magazine or whatever it was. I think they were just BSing me, for real,” she said. “I didn’t like what they were doing. You’re coming down Kensington Ave. like you’re ready for some war, with bulletproof vests. You’re in front of people doing their needles and stuff, at their worst time. This is not what people need to see. People need to see people being helped.”

Cartagena will be participating in a community Zoom meeting about the effects of photojournalism on Kensington. It is coordinated through the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (PPAC), a community photography studio and exhibition space in the Crane Arts Building in Kensington.

“Do No Harm: Community, Cameras, and Respect” on Friday evening will be an online community discussion that anyone can join, to share experiences with photojournalists in the neighborhood and talk about the impact of documentation on Kensington.

The panel was developed in part by Tony Heriza, a documentary filmmaker working on a film about the Storefront, an art and community services hub set up in Kensington by Mural Arts Philadelphia.

Heriza became interested in Kensington after seeing a 2018 article in the New York Times magazine about the drug epidemic in the neighborhood.

“What we saw from that article was how a lot of the life of the people and the hopes of Kensington were not documented,” he said. “We felt we could address what was going on, but with a different tone and a different angle on the community.”

The film, with the working title “Storefront,” is being produced by Hidden River Films. Heriza is nearly finished and hopes to release it early next year.

Heriza, like many other journalists and documentarians who have come to Kensington, is an outsider. He said his approach is different from many other documentarians in that he came to tell the story of the community’s response to the opioid epidemic, rather than the epidemic itself.

To do that, however, he still had to show that there is a serious problem in the streets.

“It’s complicated,” he said. “There’s a crisis there. In order to make people aware of it you somehow have to illuminate it. And that means documenting it.”

The name of the community forum, “Do No Harm,” comes from the ethical standards of journalism to which Heriza aspires. That means more than just getting permission from subjects to film them, but making sure they understand how the footage will be used.

Ethical journalism is further complicated by the opioid crisis, where willing subjects may not be behaving in their own self-interest. People in the grip of addiction may or may not realize the long-term consequences of the agreement to participate. YouTube videos, after all, have a long shelf life.

Ideally, said Heriza, a story will show both the good and the bad of a person or community, not just the sensational.

“The Storefront was a creative, interesting place to see both a response to the opioid epidemic, and see individuals in all their complexity,” Heriza said. “Even if they are struggling with addiction, you can see their complexity.”

During Friday evening’s “Do No Harm” forum, one of the topics that will be addressed is how cameras “can harm and how they can help.”

From the perspective of lifelong Kensington resident Calvin Walker, they can’t help. Since the opioid crisis broke in the national media, he has not seen anything positive come out of the coverage.

“I hear more criticizing than rebuilding the community,” he said.

Walker works with Rock Ministry in Kensington, a faith-based organization that is devoted to helping those on the margins of society. When not working his day job helping veterans, he spends a lot of time talking to people experiencing homelessness and addiction in the neighborhood.

“I know my community because I grew up in my community,” said Walker. “I spend more time out there trying to heal and calm things down. I have a personal relationship with people on the street. I used to be homeless myself.”

He also talks with reporters and photographers, calling them out when they drop into the neighborhood just to portray its despair. He rarely sees any of them asking permission from those they photograph.

“People’s civil rights have been violated by photographers,” he said. “I understand there is public awareness, but with photographers exposing so many people’s sorrows and pain, and feeding off of it, they are exposing all the negativity in our community as we are trying to rebuild and heal.”

As of Thursday, the day before the “Do No Harm” online forum, interest was high. About 130 people had registered to participate, and the organizers at PPAC plan to have smaller break-out sessions to better foster conversation.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.