It’s not brain surgery: HUD Sec. Carson discusses housing policy in Philly

The Veterans Multi-Service Center feels squeezed into Old City, huddled next to the immensity of the Ben Franklin Bridge. Part of Philadelphia’s aid infrastructure for former soldiers who have suffered hard times, the center’s unassuming red brick exterior belies the essential work that occurs within, aided by funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

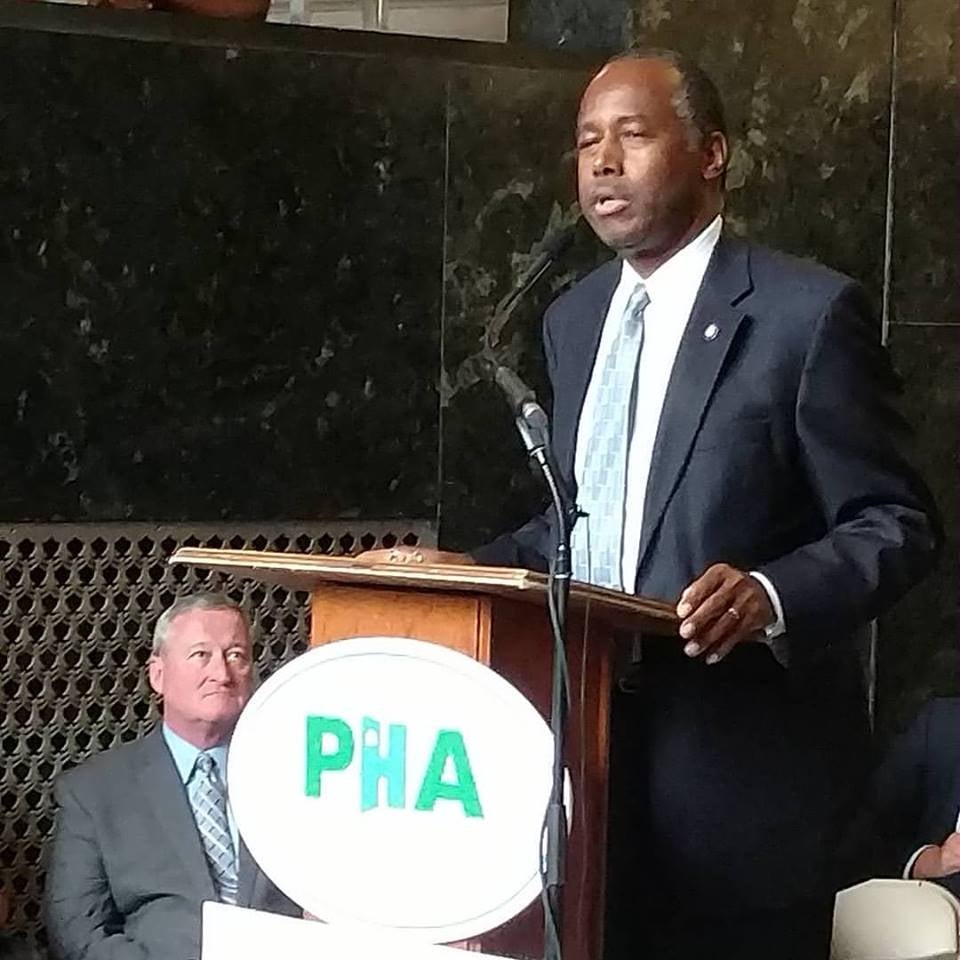

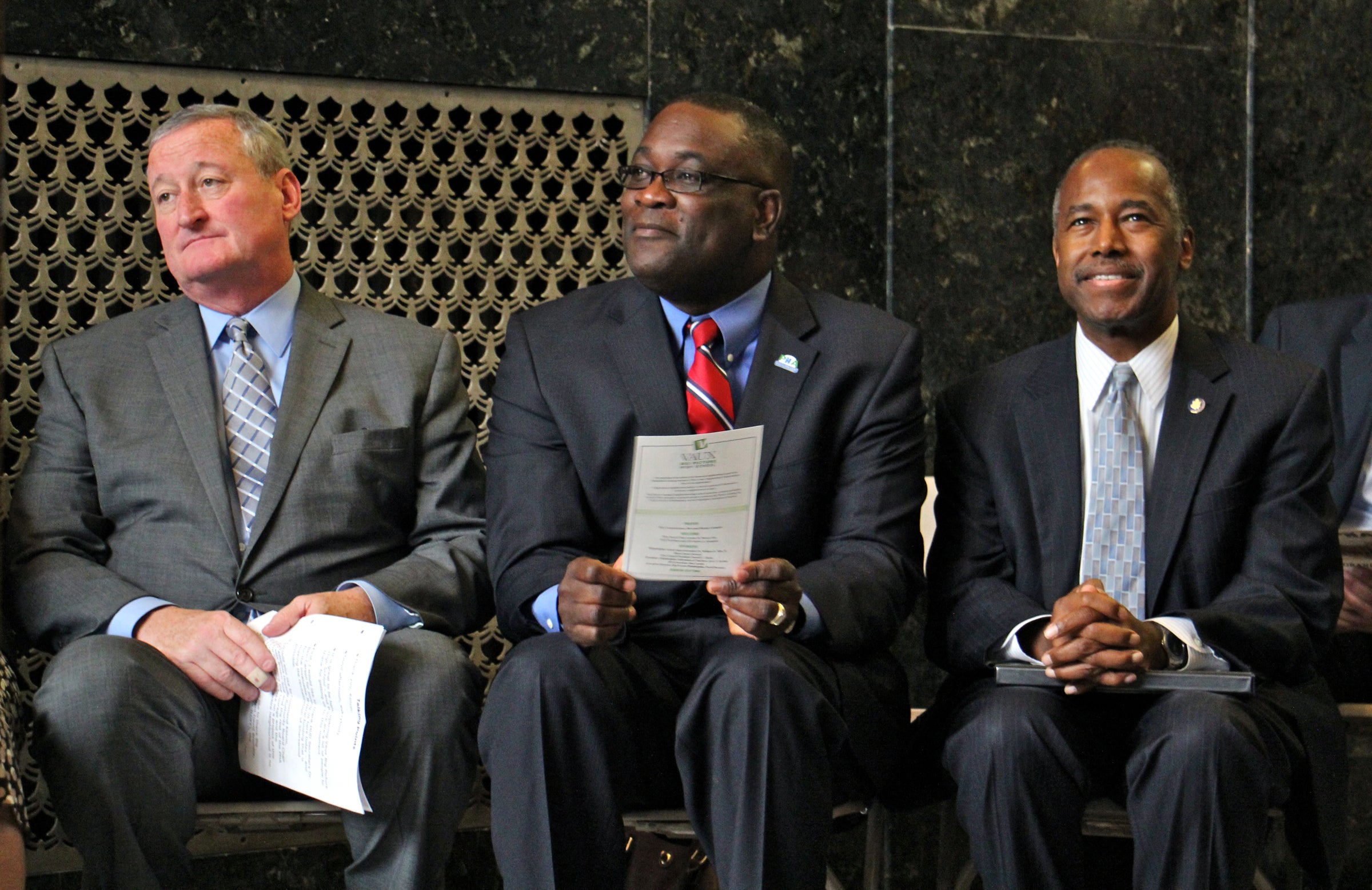

Late on Tuesday afternoon, HUD Secretary Ben Carson toured the facility, the conclusion of a long day in Philadelphia. Carson had met earlier with a group of religious leaders, staff at the local HUD office, and with employees of the Philadelphia Housing Authority. Carson also participated in the ribbon cutting for the Vaux Big Picture High School in North Philadelphia, the centerpiece of PHA’s $530 million Sharswood neighborhood redevelopment plan.

The Vaux School ribbon cutting attracted throngs of reporters, agency staffers, and local politicians, but Carson toured the Veterans Center relatively unescorted. In fact, PlanPhilly was the only news outlet that showed up for this choreographed media event and press conference. The center’s director for housing, Kathy Salerno, showed him around and explained the center’s wraparound services and how they’ve helped homeless veterans find housing.

“We have the ability to do this, as a nation, beyond veterans,” mused Carson, as Salerno and other Veterans Center executive staffers guided him toward the next stop on his tour.

In the tight confines of the institution’s fourth floor, the group shuffled toward the day drop-in center where roughly 20 men sat eating and, until the Secretary’s approach, playing bingo. Chatting with vets as cameras roll and reporters jot notes is standard PR fare for most political appointees, and an opportunity hammier politicians eat up with relish. But Carson just stood quietly at the threshold of the dining room, nodding as the Veterans Center’s leadership hovered around him.

After a minute and scarcely a word, Carson stepped back from the room, turned away, and softly continued downstairs to the next phase of his tour.

In Carson’s short time at HUD, anti-homelessness efforts have been an oft-mentioned priority, and it’s clear why he hailed the federal commitment to house homeless veterans. A big effort began under the Obama administration and has been widely considered a success, thanks in no small part to Congress’ willingness to devote significant resources to the effort, resulting in new housing construction and new money for rental assistance. Many cities, including Philadelphia, can say with only slight exaggeration that they have eliminated veteran homelessness.

Carson’s offhand comment about expanding such an effort beyond just veterans would be a welcome development for homeless advocates across the country.

“If we can give people good options, they almost always take them,” said Laura I. Weinbaum, vice president for public affairs and strategic initiatives at Project Home. “The reason we have street homelessness among people who aren’t veterans is that we don’t have the ability to say: ‘Here’s keys to a new apartment.’ That’s the beauty of the veterans’ program — the amount of resources. There were actually new housing units and new vouchers and new supports created.”

Duplicating and expanding this effort would strike a serious blow against homelessness. It would also be enormously expensive. Housing advocates told PlanPhilly that they all appreciated Carson’s comment but also all doubted it would be enacted under an administration that began its tenure by proposing an almost 15 percent cut to HUD’s budget.

Budgetary questions loomed over Carson’s day in Philadelphia. Both of the Republican-controlled branches of Congress have rejected the Trump administration’s slashing cuts to HUD in their appropriations bills. But the future remains uncertain, and critics say the secretary has been an indifferent advocate for HUD.

The funding anxieties of advocates and local politicians were periodically palpable during Carson’s time in Philadelphia. Without mentioning Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) by name — which Trump’s HUD budget would have zeroed out completely — Mayor Jim Kenney devoted about a third of his remarks at the Vaux school to praising city programs funded by the endangered policy.

“Homeowners need foreclosure prevention assistance and programs like the Basic Systems Repair Program to avoid falling into poverty,” said Kenney. “Since 2008, federally funded programs like these have saved over 11,000 homes from foreclosure. By continuing to support these programs, Dr. Carson, you allow these individuals to stay in their homes, you give their children a chance to succeed.”

Reporters were unable to ask questions following the ribbon cutting, but HUD staff did set aside some time for a press scrum following Carson’s tour of the Veterans Center. Besides PlanPhilly, no other media outlet showed up to interview the nation’s top-ranking housing official and former presidential candidate.

Although Carson didn’t mention the mayor’s plea for the preservation of federal funding in his remarks at Vaux, PlanPhilly asked him about it during the de facto one-on-one interview at the Veterans Center. Carson hand-waved away Kenney’s concerns, as he did with other questions about potential cuts to HUD and the future of specific programs.

“There is a lot of money in the CDBG pipeline, it’s going to take years to dry that up,” said Carson. “Even if we were to say there will never be another penny, it would still go on for years.”

It would not. CDBG funding is allocated to jurisdictions on an annual basis. If the Trump administration succeeded in eliminating CDBG, as originally suggested in its fiscal year 2018 budget, the money would run out by the subsequent fiscal year. The City of Philadelphia, for example, would face a budget hole of almost $40 million.

Carson went on to say that the fate of any particular programs isn’t important. Even if one policy or another were eliminated or dramatically reduced, Carson argued that HUD would find a way to re-create whichever important outcomes it produced. The secretary insisted that by laser-focusing on what works, his agency will be able to accomplish more with less.

“It doesn’t matter what the final budget is,” said Carson. “We are looking at how we spend the money efficiently. How do we protect the taxpayers and get the maximum bang for the buck? If we get $10, we will spend it extremely well. If we get $10 trillion, we will spend it extremely well.”

Carson intimated that he can always find money for proven programs, partly through ingenious efficiencies and by reducing what he sees as endemic bureaucratic bloat. But HUD and its programs have already been cut to the bone, housing advocates contend. HUD’s public housing capital and operations budget saw funding fall by one-fourth between 2001 and 2014. Unmet capital needs surpassed $26 billion as of 2010.

CDBG’s budget has also been pared back almost every year since the beginning of George W. Bush’s presidency. In 2001, adjusted for inflation, Philadelphia received $97.8 million from the program. Today, the city receives less than half that amount.

All of this austerity comes in the midst of a housing crisis that has vastly overmatched HUD’s current capacity. Only one-fourth of Americans eligible for rental assistance receive it, even as more and more renters face eviction. According to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), for every 100 extremely low-income households, there are just 35 houses affordable and available to that population.

“This administration talks a lot about how to squeeze the most out of every dollar,” said Diane Yentel, president and CEO of NLIHC. “But the amount of funding absolutely matters. This is not a problem where we don’t know which solutions work. It’s that we aren’t funding these solutions at the levels necessary to meet the need.”

Yentel specifically cites Section 8 vouchers — which don’t require the construction of new buildings — as a relatively easy and cheap way to address the housing crisis. Many national housing experts believe the program should be expanded to every American who is income-eligible for it, much like food stamps. (Recently appointed HUD Deputy Secretary Pamela Hughes Patenaude said last year that “Looking at the expansion of the housing voucher program is high on our list [of policy options].”) Instead, Trump’s budget proposal would have fallen especially hard on the Section 8 voucher program, forcing recipients to pay more in rent and reducing the total number of vouchers by a couple hundred thousand.

Even as he defended potential cuts to HUD, Secretary Carson promoted other programs that he believes should be expanded. These include the Moving To Work policy which, confusingly, has little to do with transportation and everything to do with giving housing authorities the flexibility to spend federal dollars as they will. Carson also enthused about the Rental Assistance Demonstration policy, which seeks to attract private capital to address the yawning maintenance needs gap in traditional public housing.

During his conversation with PlanPhilly, Secretary Carson also praised “housing first” policies as an example of the kind of proven program that HUD would always fund. Many programs aimed at helping homeless individuals try to address the underlying causes of their predicaments, offering free or subsidized housing as a carrot to induce sobriety or encourage a job hunt. Housing first advocates believe homeless individuals should be housed first, and then issues like addiction or unemployment can be addressed later.

In June, a cadre of Republican Congressional representatives lobbied Carson to repeal HUD’s preference for housing first measures, calling it “one of the worst examples of Washington’s we-know-better-than-you mentality.” But the HUD secretary remained firm in his support of the doctrine, and described it as both a humane and efficient answer to homelessness.

“The housing first initiative indicates an understanding that it actually costs more to leave someone on the street than it is to get them off the street,” said Carson. “[Then you] diagnosis why they are in that position, that’s housing second, and housing third is you fix it. A lot of people who find themselves in difficult situations actually have a great deal of potential and can become self-sufficient.”

Yentel said that after seeing the appropriations requests from Congress, she doesn’t expect HUD’s capacity to be reduced by a sixth as Trump originally proposed (although she thinks some smaller snips may be enacted). She believes similarly brutal cuts will be put forward by the Trump administration next year, although she notes that last year’s proposal was issued with no input from Carson.

Now back in Washington, the Secretary and his staff at HUD will soon be tasked with crafting their budget requests for next year. Yentel, Weinbaum, and other housing advocates said that they hope Carson’s apparent passion for anti-homelessness programs will be visible in a HUD office willing to fight for such priorities.

Ed. Note: After publication, PlanPhilly was informed that reporters from the Inquirer showed up after our reporter finished his interview with Secretary Carson, and briefly interviewed him as he left to catch his train back to Washington D.C. PlanPhilly was the only outlet at the scheduled opportunity to ask the Secretary questions.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.