In cities, the highest amputation rates are associated with poverty and being Black, a new study shows

Amputation rates have long been higher in rural America. But in cities, the highest rates are associated with poverty and being Black, a new study shows.

Amputation rates have long been higher in rural America. But in cities, the highest rates are associated with poverty and being Black, a new study shows. (XArtProduction / BigStock)

Amputation rates for patients with peripheral artery disease, or PAD, have long been higher in rural America than in cities, largely because of a lack of access to specialty care. For years, health researchers have studied this from a geographic standpoint, on the county level. And the research consistently finds that counties that are poor, counties that are more rural, and counties that have fewer physicians tend to have higher amputation rates.

But the vast majority of Americans live in U.S. cities. A new study suggests that the highest PAD-related amputation rates in urban areas are associated with poverty and living in a majority Black neighborhood. Alexander Fanaroff is the study’s lead author, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and an interventional cardiologist.

“The genesis for this study was [seeing whether] risk factors for amputation and inadequate medical care act at a smaller level than the county,” said Fanaroff. “Living in Philadelphia, [you see] neighborhood-to-neighborhood variation in resources available to the people that are living in these communities. And when you look at things on a county level, I think a lot of that gets lost.”

Fanaroff said he and his colleagues wanted to describe amputation rates on a ZIP code-level around the United States and look at the association between those rates and ZIP code-level markers of racial composition and poverty.

For the study, researchers looked at Medicare claims data from 188,995 patients who underwent a total of 222,956 PAD-related major lower-extremity amputations between 2010 and 2018. And they collected the total number of amputations per hundred thousand Medicare beneficiaries in each ZIP code in the United States.

More than 75% of patients undergoing major amputations lived in metropolitan areas. And more than half of the ZIP codes with the highest amputation rates were also in cities, the study found.

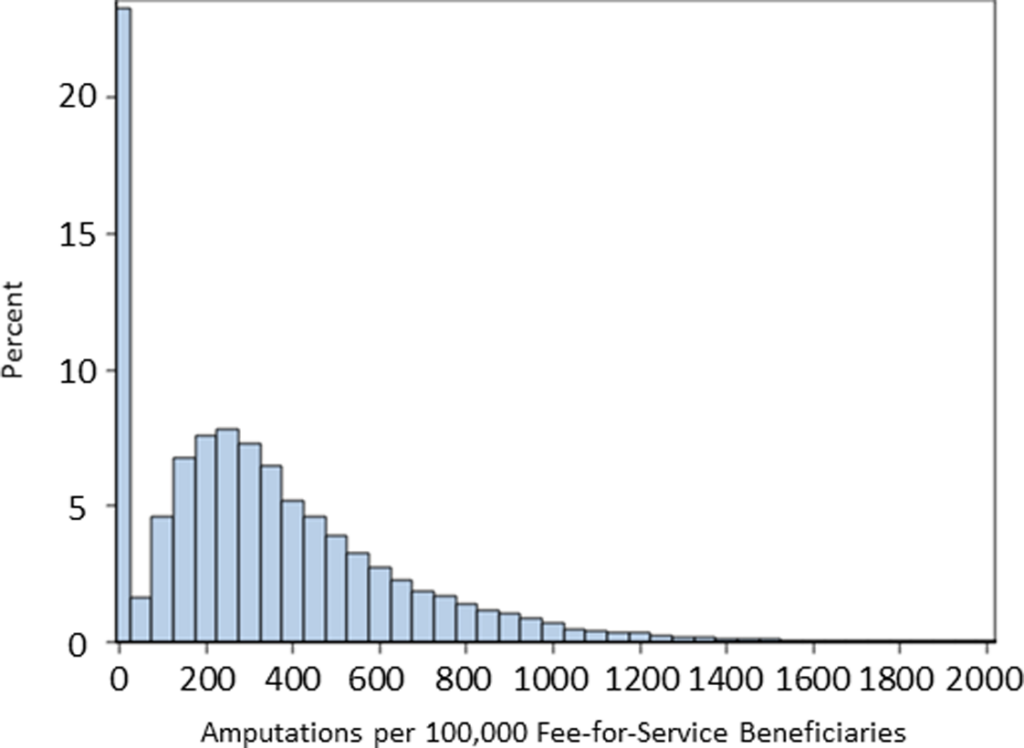

ZIP code–level amputation rates ranged from 0 to 7080 major amputations per 100 000 Medicare fee‐for‐service beneficiaries.

In cities specifically, ZIP codes with a greater proportion of Black residents had higher amputation rates than ZIP codes with lower proportions of Black residents, and 76% of majority Black ZIP codes were in the top quartile for amputation rates.

Peripheral artery disease and amputation

Peripheral artery disease — a blockage in the arteries of body parts that are not the heart — is typically caused by a process called atherosclerotic vascular disease, a hardening of the arteries. And over time, that causes restriction of blood flow to the lower extremities, which can lead to amputations.

Fanaroff said there are a number of ways health care providers can work to stop or slow the progression of peripheral artery disease before a doctor has to amputate a limb. Diet and exercise are one component. Monitoring and treating other health conditions, such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol, with medicines are another, as are smoking cessation interventions. He said there’s also limb salvage, a process of revascularizing a threatened limb that has had its blood supply severely limited. (Inserting a stent into the heart is a common example of revascularization.)

“So when you talk about an amputation, an amputation is a failure at multiple levels there,” said Fanaroff. “And we know, in our backyard of the University of Pennsylvania Health System, in our own ZIP code, amputation rates are high despite the availability of dozens of folks that specialize in treating that condition.”

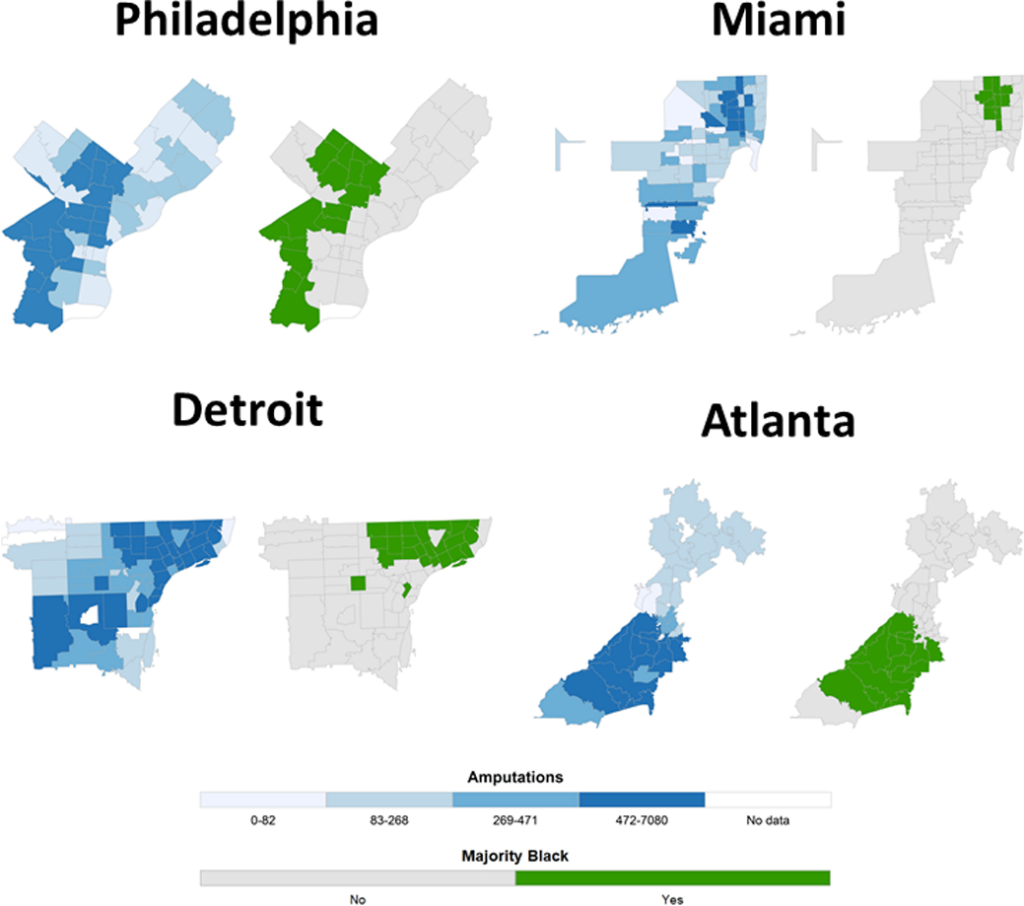

Shown are ZIP code–level maps of amputations per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries (unadjusted) in Philadelphia, Dade (Miami), Wayne (Detroit), and Fulton (Atlanta) counties with parallel maps indicating ZIP codes with ≥50% Black inhabitants. Majority Black ZIP codes overlap with high amputation rate ZIP codes.

Previous studies focused on the lack of proximity to peripheral artery disease specialists in rural communities as a major contributor to high amputation rates there. Yet cities with high amputation rates typically have close access to medical providers, and racial and socioeconomic disparities still persist, the new study showed.

Fanaroff said he and his colleagues created maps of cities and metropolitan areas across the U.S. and looked at where high amputation rate ZIP codes were compared to where majority Black ZIP codes were.

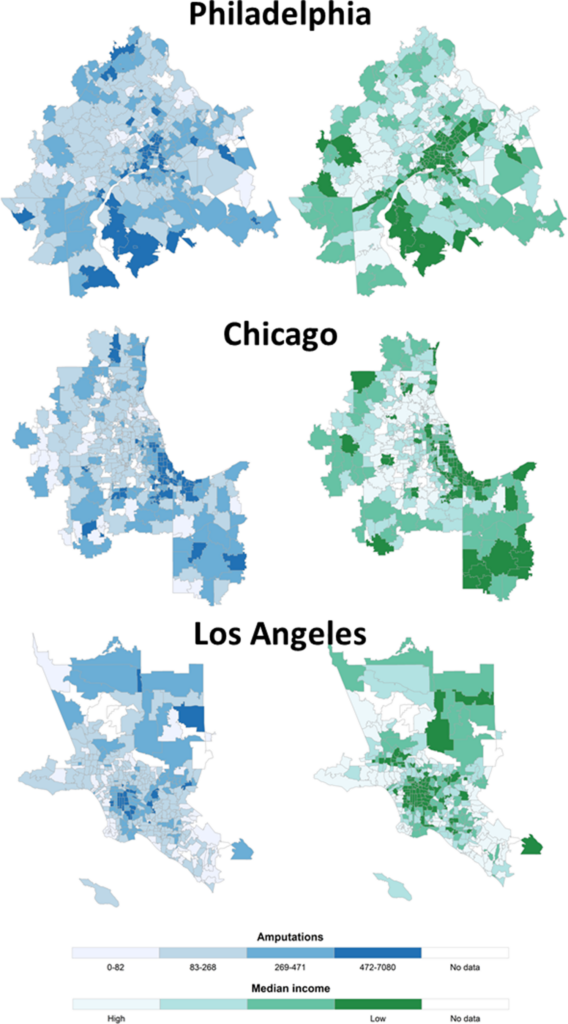

“And when you sort of map them out, we found that the high amputation rate ZIP codes and the majority Black ZIP codes were the same ZIP codes,” said Fanaroff. “And similarly, we found that the high amputation rate ZIP codes and the low-median-income ZIP codes overlapped.”

According to Fanaroff, there are decades’ worth of research in the medical literature on the association between residential racial segregation and poor health care outcomes, and this study draws on that work. He said residential racial segregation in the United States results in a disproportionate number of Black people living in areas of concentrated poverty. And living in a high-poverty neighborhood is associated with fewer job and educational opportunities, increased exposure to chemical or psychosocial stressors, and less investment in that neighborhood by government and the private sector.

That makes it more difficult for people living in a low-income area to access primary care and subspecialty care, which in turn leads to inadequate treatment of chronic illnesses.

“And that leads to worse health outcomes, which in our study we found is higher amputation rates,” said Fanaroff.

Care for PAD lags behind

When you look at patients with peripheral artery disease, Fanaroff said, what you see is that best practices are too infrequently followed. National quality improvement efforts have bettered the care of patients with cardiovascular disease, but care for patients with PAD lags behind. Antiplatelet therapy and aspirin are the two medicines most commonly used to treat the disease, and research shows these medicines reduce amputation rates and other major adverse limb events in patients.

“But when you look at these national representative samples, only about a third of patients with heart disease are getting this medication,” said Fanaroff. “Same thing with statins [cholesterol-lowering drugs], same thing with smoking cessation counseling. We’re just not delivering care that we know helps folks.”

In a nationally representative assessment of office‐based practice, only 36% of outpatients with PAD received antiplatelet therapy, 33% received statins, and 36% of smokers received smoking cessation counseling. But lack of access to care was not limited solely to primary and secondary prevention therapies: 32% of patients with Medicare coverage who underwent lower-extremity amputation did not receive any diagnostic arterial testing in the 12 months before the amputation.

Shown are ZIP code–level maps of amputations per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries and median income in the Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs); darker colors represent higher rates of amputation and lower median income. Each of the 3 large, representative MSAs shown have multiple ZIP codes with top quartile amputation rates, with many colocalized to ZIP codes with low median income.

Community-level interventions for preventing PAD

Experts note that unlike certain kinds of cancers or chronic conditions, there are no standardized national guidelines for screening for peripheral artery disease. But Fanaroff said that in various communities around the country, there are efforts to start mass screening of patients for PAD. The earlier you can detect the disease, he said, the sooner you can initiate good secondary therapies.

On the broader level, efforts to better educate patients and providers are also key. Teaching patients what kind of symptoms to look out for and report to their doctor is one component. And ensuring that clinicians know the right questions to ask or when to recognize when a reported symptom may be a sign of PAD could be life-saving.

Though this study did not focus on specific barriers to care for high-amputation-rate ZIP codes in metropolitan areas, Fanaroff said future studies will need to look at those community-level barriers. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in amputation rates are not just about how much access to a doctor an individual may have, he said.

“It’s [also] the ability to take off time for work, the ability to have a safe place to walk to get exercise, to have fresh fruits and vegetables available to access, to be able to get to a pharmacy that has the medicine,” said Fanaroff. “ It takes a lot more than geographic proximity to see a doctor to maintain health.”

—

Support for WHYY’s coverage on health equity issues comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.