Racial gaps in breastfeeding are closing. Philly area Black birth workers are one reason

Black women historically had the lowest rates of breastfeeding initiation, but new data shows that’s changing. Community support makes the difference.

Listen 1:11

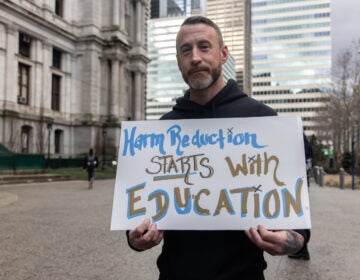

Jabina Coleman (center) surrounded by members of the Breastfeeding Awareness and Empowerment Cafe (BAE Cafe) , a group for Black birthing mothers in PA to connect and support each other through their birthing journeys. (Photo courtesy of Jabina Coleman)

Breastfeeding gaps between Black and white mothers have existed for as long as the government has collected data on those rates, since 2000.

In 2018, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Immunization Survey-Child, about 84% of U.S. mothers said they breastfed their babies. But when researchers broke down that number by race, 85% of white mothers said they breastfed, more than the 75.5% of Black mothers who said the same — a 9.5% disparity.

Saleemah McNeil says this is not about a question of choice. McNeil remembers having trouble breastfeeding her child just days after giving birth in 2006. She remembers an impatient hospital staff who offered her little help.

“I had a very abrasive lactation consultant come and try and support me while we were in the hospital, and my son just would not latch on,” recalled McNeil, who lives in Philadelphia. “And I felt that the nursing staff was very impatient.”

That was all just a few days after McNeil had survived a traumatic birth experience, in which she was rushed to the hospital and delivered her son earlier than expected.

The memory of the hospital’s lack of care for her birthing journey, especially her breastfeeding struggles, have stayed with McNeil over the years. She remembers the hospital sending her home with bottles of baby formula. Her sister, who had already breastfed two children at the time, ended up assisting her.

“And [my sister said] you get used to [the nausea], that goes away,” said McNeil. “And ultimately it did. So when I think about just her providing me with that small bit of encouragement and information, it really helped my journey.”

According to multiple qualitative studies, Black women identify breastfeeding to be the healthiest and most desired feeding method for their infants. And without the support and knowledge her family was able to impart to her, McNeil said, her path to breastfeeding would have been a lot harder. During her life, she’s seen countless Black mothers trying to breastfeed and either lacking the support or being separated from their kids before they are able to do so.

For half a decade, McNeil worked at Riverside Correctional Facility in Philadelphia, where she assisted incarcerated women with their birthing journeys as a doula and an instructor of maternal health classes. Working in corrections and bearing witness to the lives of the women she served ignited anger and passion within herself, she said.

“[Incarcerated women] would immediately be separated from their child within 48 hours [of giving birth] and then be back to the jail,” said McNeil. “However, I found myself day in and day out listening to the life story of these newfound parents. And I knew that I needed to do something greater to help them remain out of jail when they got the opportunity to be released, which is why I became a therapist.”

Meeting the need

McNeil long dreamed of creating an access point of care for Black people after noticing those adverse experiences in the health system at her workplace and in her own life. What at first started as a desire to meet the needs of incarcerated mothers has expanded into a wider vision. McNeil is now a reproductive psychotherapist and the founder and CEO of Oshun Family Center, a nonprofit organization that aims to provide racially concordant care to Black birthing families and members of the Black community through telehealth therapy and a range of maternal health support services for every stage of the birthing journey.

In 2019, Oshun Family Center launched the Maternal Wellness Village, a network of Black birth workers, doulas, therapists, and lactation consultants who focus on the intersection of racism, racial trauma, and maternal health. With no brick-and-mortar location just yet, the Oshun center connects individuals and families to culturally competent clinicians and health workers within their network to help them navigate challenges such as postpartum depression, anxiety, traumatic birthing experiences, and lactation issues.

“Racially concordant care is so important because I think it helps work through the initial barrier of creating trust,” said McNeil. “And what we do know is that there is a lot of mistrust with the Black community in the medical system due to … generations long of mistreatment of Black bodies.”

Jabina Coleman is a licensed social worker, the founder of Lifehouse Lactation and Perinatal Services, and she works as a board-certified lactation consultant within the Oshun Family Center’s Maternal Wellness Village. She specializes in the clinical management of breastfeeding.

A lot of Coleman’s work involves listening to new parents and supporting them through the challenges of postpartum life. Whether that’s helping a new mother make the decision to breastfeed or helping families make the transition from the hospital to their home, she wears many hats.

“Some people are also doing this alone,” said Coleman. “And being that we’re in the pandemic, it makes it even harder for people to build community around lactation. And having a successful lactation and infant-feeding journey is really [about] having a supportive network of people around you.”

Access to culturally competent breastfeeding care lags

In 2018, Coleman founded Breastfeed Awareness and Empowerment, or BAE Cafe, a support group for new moms in which she promotes and supports breastfeeding. Here, Black mothers can connect with one another about challenges they may be facing, trade advice, and become a part of a birthing community. Coleman said the power lies in seeing Black women who look like you, who have overlapping birthing experiences, and who can speak to how they overcame those challenges.

International board-certified lactation consultants like Coleman have been shown to improve breastfeeding initiation in women overall, including women of color. But a 2018 study found significant racial discrimination against patients of color within the field. According to researchers, a common presumption was that women of color did not want to breastfeed, and as a result were given fewer lactation referrals, received lower priority, and got less attention and support. There were also reports of racist comments made by colleagues and increased referrals of Black mothers to social work and long-acting birth control.

Physician Dr. Zaneta Forson-Dare is a neonatal-perinatal fellow at Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital and health researcher who focuses on breastfeeding disparities. She said the racial diversity of lactation consultants is lacking. Lactation consultants of color face restrictions in accessing clinical credentials and gaining employment, making them less available.

“And there’s geographical differences [in access to] lactation consultants,” said Forson-Dare. “So areas that have higher Black populations [tend to] have less lactation consultants.”

For many Black mothers, access to culturally competent care for those who want to breastfeed serves as a significant barrier.

Why have breastfeeding disparities lasted for so long?

Black people disproportionately experience a number of barriers to breastfeeding, said Coleman, including lack of knowledge about it, lack of peer, family, and social support, insufficient education and support from health care settings, and concerns about navigating breastfeeding and employment.

For years, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended that mothers exclusively breastfeed infants until at least six months, and then combine breastfeeding while introducing new foods until at least 12 months. Coleman said infants who are breastfed have reduced risks of asthma, obesity, type 2 diabetes, ear and respiratory infections, and sudden infant death syndrome. There are even benefits for the mother. Breastfeeding can help lower a mother’s risk of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and ovarian and breast cancer.

“And when we talk about breastfeeding rates, what we’re looking at is the initiation, exclusivity, and longevity,” said Coleman. “So are Black women initiating breastfeeding? Are they exclusively breastfeeding, which means not introducing anything but human milk during the first six months of life? And how long are they breastfeeding?”

But research shows returning to work is a major barrier to breastfeeding initiation and continuation, particularly for Black women. According to a 2014 CDC study, a woman’s plans for returning to work are associated with her intention to breastfeed. Women planning to return to work before 12 weeks postpartum or planning to work full time were less likely to intend to exclusively breastfeed, compared with women planning to return to work after 12 weeks postpartum or women planning to work part time. And Black women, especially those with low incomes, return to work earlier than do women in other racial/ethnic groups and are more likely to experience challenges to breastfeeding, including inflexible work hours.

“I’ve worked with [Black] women who have had to go back to work and before returning back, we’ve talked about talking with [their] supervisor or [their] manager, getting a plan in place, making sure that [they] have a clean and sanitary space to pump, making sure that folks have access to a pump,” said Coleman.

Experts say socioeconomic status is an influential intersecting factor in the health disparities between Black and non-Black women and their infants, but racial disparities persist even in Black women with high incomes and advanced degrees. There is evidence that Black women with advanced degrees actually have worse obstetric and neonatal outcomes than do non-Black women of low income or those without a high school diploma, which indicates that race, not class, is the consistent, influential factor.

And previous research shows that hospitals in the United States that serve majority-Black populations are less likely to help Black women initiate breastfeeding. Experts say helping women initiate breastfeeding within the first hour of birth and not providing breastfeeding infants with infant formula without a medical indication increases rates of breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity.

‘Systemic racism in health care may be playing a part’

In 1991, the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) launched the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), a global, evidence-based program to increase breastfeeding through standardized protocols.

Forson-Dare, of Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital, said there are specific requirements hospitals have to meet to be a Baby-Friendly Hospital, including lactation support. In 2021, Forson-Dare and fellow researchers published a study that looked at breastfeeding initiation and longevity data from a Southeastern academic institution before and after BFHI implementation. They found that after BFHI implementation, mothers were overall 1.17 times more likely to initiate breastfeeding. Black mothers in particular saw the biggest benefit. Their breastfeeding initiation increased to 66%, from 52%.

But Forson-Dare said racial disparities still persisted, even after controlling for socioeconomic factors and chronic conditions.

“When we looked at even just sustaining [breastfeeding] to the end of the hospital stay, when you stratify it by race, for non-Black mothers that was around 85%. But for Black mothers, that dropped down to 69%,” said Forson-Dare.

In other words, Black mothers were more likely to start breastfeeding after BFHI-implementation, but they experienced significant challenges in sustaining their breastfeeding through their hospital stay and post-discharge. Forson-Dare said there’s clearly a history of negative health outcomes in the Black American population, but there shouldn’t be significant gaps in breastfeeding initiation between women of different racial groups who gave birth in the same Baby-Friendly Hospital.

“When [Black women] get to the hospital, there is an increasing concern that the implicit bias and systemic racism in the provision of health care may be playing a part, too,” said Forson-Dare.

And according to Coleman, there’s a historical component to breastfeeding disparities that isn’t always talked about. During slavery, Black women were forced to breastfeed white children instead of their own, and after slavery that practice continued as Black women served as domestic wet nurses in the homes of their white employers.

“I think there is this generational trauma that exists around [breastfeeding],” said Coleman.

‘What are we doing about it?’

When McNeil reflects on the inception of the Oshun Family Center, she said it really started as a series of conversations between Black birth workers and clinicians in her personal network who wanted to reduce the Black mortality and morbidity rates in Philadelphia and throughout Pennsylvania. From 2013 to 2018, Black women in Philadelphia made up 43% of births, but 73% of pregnancy-related deaths. And in 2019, Black women were 50% more likely to give birth prematurely than white women, according to the CDC.

“And so with that,” McNeil said, “we came together and we thought about a program that we all needed at some point in our birthing journeys to help get to the next phase in the fourth trimester, to work through postpartum depression or anxiety, to work through lactation issues, to cope with the traumatic birthing experience that [someone] may or may not have had.”

And in recent years, the racial gap in breastfeeding initiation between Black and white women has been getting smaller. In 2011, there was about a 19% disparity between Black and white mothers who initiated breastfeeding, with 81% of white mothers saying they breastfed, far more than the 62% of Black mothers who said the same. But by 2018, that gap closed to 9.5%, with 85% of white mothers and 75.5% of Black mothers saying they breastfed.

Forson-Dare, of Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital, said even though the gap is closing, health systems still have not achieved full equity. Increases in breastfeeding initiation are welcome improvements, she said, but researchers still need to understand why Black women may not be sustaining their breastfeeding at similar rates than other racial groups.

Still, said Jabina Coleman, the Pennsylvania-based lactation consultant, those increases in breastfeeding initiation are cause for celebration.

“[Black women] are breastfeeding, and I think we often lead from this deficit narrative … but I beg to differ,” said Coleman. “There are challenges, [but] there are many of us that are out there doing the work, supporting the community.”

In 2016, Coleman and co-founder Rebecca Duncan started BBQ for BAE, which stands for Beautiful Black Queens for Breastfeeding and Empowerment. It’s an annual event hosted during the last week of August in honor of National Breastfeeding Month. Black families and birthing individuals gather each year in West Philadelphia to eat, listen to music, and learn about breastfeeding.

And this year, the Oshun Family Center’s Maternal Wellness Village program, in collaboration with Temple University, received a five-year, $5.99 million award from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute to compare two approaches for reducing heart disease risk factors in Black people people who have given birth. The overarching goal of the study is to eliminate disturbing disparities in heart disease, including heart attack and stroke, among Black people who have given birth during and after pregnancy.

“We worked with Temple University to go after funding that will allow us to not only work from the bottom up, which is us providing the services to the community to help circumvent some of those outcomes, but also the top down,” said McNeil.

McNeil and her team want to train health care administrators and clinicians in trauma-informed care meant to reduce maternal health disparities for Black people. She said that she’s excited for the future of the Oshun Family Center, and that the organization is raising funds to open a physical location in the coming years.

Coleman, the lactation consultant, said holding local, state, and federal entities accountable for ensuring that the health of Black women is prioritized is also imperative to reduce these racial health gaps.

“It’s really important that we understand the importance of Black breastfeeding and the barriers that exist, but I don’t feel like we need to continue to talk about those barriers because we know they exist,” said Coleman. “They’ve existed for many, many, many decades. And the question is, what are we doing about it?”

Subscribe to The Pulse

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.