Implicit in tackling racial biases, an expert says: Knowing the history

It comes after a hotel staff member wrote a three-letter slur against those of Japanese ancestry on a hotel guest’s room folio last week.

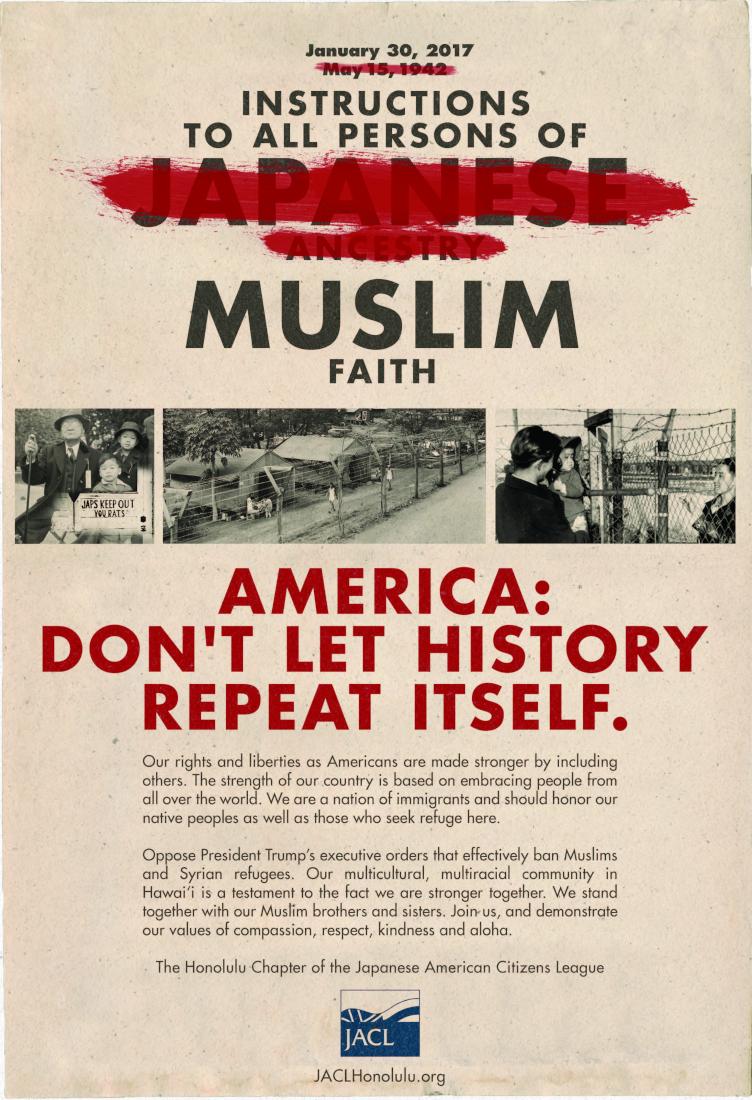

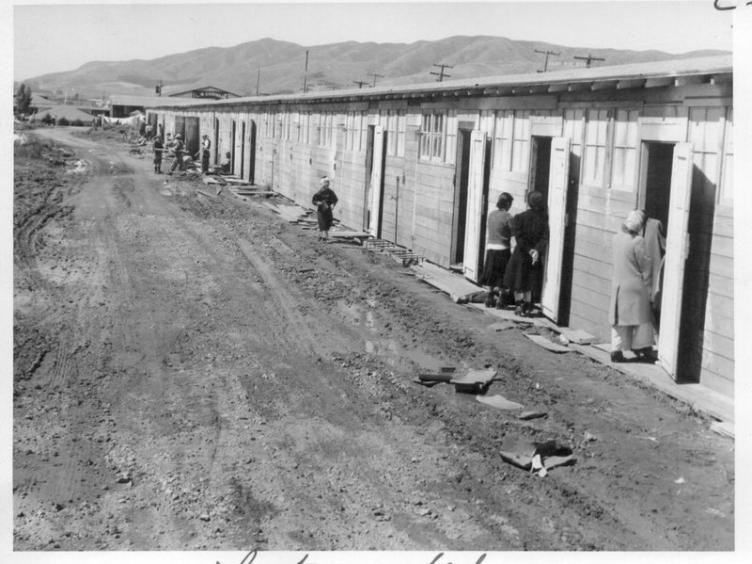

People of Japanese ancestry arrive at the assembly center at Santa Anita Racetrack in Arcadia, Calif., in 1942 for internment. (National Archives and Records Administration)

This story originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

The Sheraton Philadelphia Downtown Hotel on 17th Street hosted racial-sensitivity training for about 50 front-line employees Thursday after a hotel staff member wrote a three-letter slur against those of Japanese ancestry on a hotel guest’s room folio last week. The guest, Eileen Yamada Lamphere, had attended a national convention hosted by the Japanese American Citizens League, the oldest and largest Asian-American civil-rights organization in the country. After the incident, JACL, the Philadelphia Convention & Visitors Bureau (PHLCVB), and the Sheraton addressed the term’s derogatory nature and its historic and present-day implications in order to shape the training.

Rob Buscher, president of Philadelphia’s JACL chapter, developed and conducted the training. He said he told the group, “This isn’t punishment. I’m speaking as a Philadelphian, and I want us to do better.”

Buscher spoke to PlanPhilly about the incident, the city’s and the hotel’s response to it, and the way in which it revealed that the pains and history of Japanese-Americans in the United States, and Asian-Americans in general, have been lost in today’s discourse on racial bias, diversity, and inclusion.

Comments have been edited for clarity and concision.

—

The Japanese Americans Citizens League, the Convention & Visitors Bureau, and the Sheraton moved quickly to address the incident and came to a resolution for next steps within days, including an internal training for all hotel staff last week. Do you think the approach would have been different if this had happened before April’s incident at the Starbucks on Rittenhouse Square?

First, I think it is important to acknowledge that the Starbucks incident and what happened at the Sheraton are too different for us to compare. The fact that law enforcement was called on the gentlemen of African-American descent simply for existing in a public space is far more egregious in terms of its potential to cause bodily harm and overall severity of the incident. That said, I don’t want to suggest the Sheraton incident was/is not worth discussing with regards to the blatant racism and inherent violence attached to the term [used]… For Japanese-Americans whose families were forcibly evicted from their homes and mass-incarcerated during World War II, [the term] is a painful reminder of the days when racial violence was commonplace; a time when our community became a target simply for sharing ancestral roots with a people that our country was at war with.

While the Starbucks incident is definitely going to be used as a new benchmark for corporations to adhere to in future incidents that require employee trainings, I don’t necessarily think this is a game-changer for the lived experiences of communities of color. We would have sought a resolution from Sheraton similar to what was offered to remedy this situation.

Racial bias, cultural sensitivity, diversity, and inclusion are frequently used buzzwords lately, both in the headlines and as our society re-evaluates appropriate workplace behavior. Where do you see what happened at the Sheraton in this larger discourse?

Actually, I see much of the work that has transpired in the last couple years related to workplace culture as directly rooted in the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements. Because sexism is an issue that transcends racial/ethnic divisions, it has caused the whole of society to re-evaluate the historic normalization of sexual abuse in the workplace, which has in turn opened up a dialogue about other vestiges of social conservatism.

Do folks doing this type of training — either moderating or hiring someone appropriately skilled — have to continually pivot around new circumstances? Or is the foundation of respect and inclusion the same? Do you think that various underserved groups are more visible now?

As our society progresses over time, there are additional perspectives that must be considered in order for sensitivity trainings to be effective. If a corporation or other organization’s HR lacks the nuanced understanding to communicate the ever-shifting landscape of diversity, they have a responsibility to their customers and employees to hire a professional who is capable of delivering this content. While someone who is involved in this work may have a general idea of marginalized groups they do not belong to, nothing can compare to hearing from someone with the lived experience as a person of color, religious minority, or any other marginalized group.

Historically underserved groups are certainly more visible in today’s society, as media technology has allowed a multiplicity of narrative perspectives to surface. However, given the socially regressive rhetoric that the current federal administration has brought into mainstream political discourse, marginalized groups are also facing a backlash by some of the more conservative elements in society.

There is a larger conversation here, about the ignorance of racial slurs, Asian-American or otherwise. Some would argue that the lack of malicious intent or lack of knowledge that these slurs exist is a good thing, that it shows that we are living in a post-racial society. Yet these words — slurs — have a deeply painful history in recent memory, for some less than a generation ago. How can people forget so quickly?

Although some have suggested the ignorance around racial slurs is a good thing because they are less prevalent in today’s society, I would argue that this is almost worse. If communities are not familiar with the history of racism in this country, it becomes more difficult to convince the public at large to take the actions necessary to eradicate contemporary issues like anti-blackness, Islamophobia, and xenophobia. Any student of history should be able to draw connections between the history of African slavery and indigenous genocide in establishing a foundational racial hierarchy that created institutional white supremacy in the U.S.A. Unfortunately, our public schools tend to skip over many of the more problematic aspects of our nation’s past. You really can’t blame someone for being ignorant to this history when we aren’t being taught it in school.

Furthermore, I would argue that for many people the use of racial slurs is not a thing of the past. I rode a SEPTA bus yesterday afternoon and heard a man remark to his wife about an African-American passenger, “Look at that … in the cowboy boots.” Just because it isn’t politically correct to use these words in public doesn’t mean that people don’t still use them behind closed doors.

In addition to running the Philadelphia chapter of the JACL, you also teach courses on immigration history, activism, and Asian-American cinema at local universities. As you teach the historical context, what examples do you raise? How about the nuance of who says it, the context, or to reclaim its power? Do you name or say these slurs out loud?

Actually, I find it important to name these words, within reason. While there is a tendency to compare the derogatory term used at the Sheraton and other anti-Asian slurs to the N-word, the level of violence and dehumanization linked to the latter is simply not comparable. Being of mixed-race Japanese-American descent myself, I feel comfortable using the term in the context of educational discussion. I also acknowledge there are others within my own community who do not feel comfortable doing so. Ultimately, I think every person needs to make that decision for themselves about what they feel comfortable using, assuming they are speaking from the lived experience of the particular group that slur refers to.

The training that you conducted was closed to the public, but the messages and context that you’re sharing applies to everyone. What are some salient points that you’d like to impart to anyone reading this?

Ultimately, this training was given from the perspective that we are all on the same team here. As an advisory board member at PHL Diversity (formerly the Philadelphia Multicultural Affairs Congress), the diverse meetings and conventions branch of PHLCVB, I had a large role in bringing this convention here to Philadelphia in the first place. I am proud of my city and wanted to share that with the national delegation of the JACL. I was ashamed at the level of ignorance, and the unintended but very serious impact that this issue could potentially have on our ability to entice meeting planners from the Asian-American community to host their future events in Philadelphia.

I blame the failings of our public education system over any individual in terms of their ignorance to the history of anti-Asian racism. Unfortunately, that is not a good enough excuse for the incident that transpired to have occurred, especially in the context of this being a national Japanese-American civil-rights convention. If nothing else, Sheraton should have ensured that their front-line staff did due diligence on the organization and community that they would be hosting. As customers, we expected more of them, and this training was really geared towards providing the tools so they can better prepare for future events and daily interactions with their [Asian-American/Pacific Islander] guests.

—

Rob Buscher is president of the Philadelphia chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League. He serves as a commissioner on the Governor’s Advisory Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs and chairs its Asian American Pacific Islander Arts Collective. He is the director of the Philadelphia Asian American FIlm Festival and teaches courses on immigration history, activism, and Asian-American cinema at Arcadia University and the University of Pennsylvania. For more information on Philadelphia JACL, visit www.phillyjacl.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.