How to break into the FBI: 50 years later, Media burglars get local honors

The confidential files they stole in 1971 revealed widespread surveillance of the American public and the FBI’s infamous COINTELPRO operation.

Listen 6:30

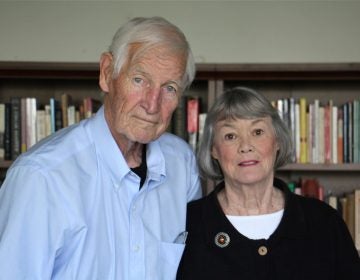

Fifty years ago, Bonnie Raines and Keith Forsyth were among a group of activists who broke into an FBI office in Media, Pa. and made off with classified documents exposing illegal FBI investigations. They are standing at the site where a historical marker will commemorate the break-in. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

We wrote this story based on responses from readers and listeners like you. In Montgomery and Delaware counties, what do you wonder about the places, the people, and the culture that you want WHYY to investigate? Let us know here.

Updated at 1:16 p.m.

“If you’re a white man in a suit, you can get away with anything.”

That’s the tongue-in-cheek way Keith Forsyth explained to his kids that he escaped scot-free after pulling off a world-changing heist.

The dapper disguises Forsyth and his accomplices donned one fateful night in 1971 were meant to help them accomplish a mission: exposing abuses of power at the highest levels. On Sept. 1, he and others will return to the scene of the crime as a Pennsylvania historical marker is erected in their honor.

“I think that the value of the commemoration is for people to hear about this story, to be reminded of the kind of things that powerful people will do if they think they can get away with it. And to be reminded of our ability to fight back and to stop that,” Forsyth, now 71, said in a recent interview with WHYY News.

Fifty years ago, a patchwork group of antiwar activists known as the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI, Forsyth among them, raided a small FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, and slipped unnoticed into the night with more than 1,000 documents. The treasure trove of confidential files laid bare the FBI’s widespread surveillance of American citizens and raised the curtain on the agency’s infamous COINTELPRO operation targeting notable leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

At the time, the fallout from the documents’ explosive public release dominated the airwaves and rattled Washington politicians and bureaucrats alike. Because it preceded publication of the Pentagon Papers by only a few months, it served as an important precursor for the Washington Post editors who would soon be gifted with a wealth of different government secrets.

But for years, the major players in the Media FBI heist and the key events of the night of March 8, 1971, were shrouded in mystery. For good reason: The burglars had pledged a vow of secrecy until the legal shot clock known as the statute of limitations ran out.

Though the burglars broke their silence some time ago, the public’s memory of the event has largely waned. But on Sept. 1, for the first time since the night of the burglary, some of those involved will return to the scene of the crime to celebrate the unveiling of a Pennsylvania historical marker at 1 Veterans Square in Media.

There will be speeches, a book signing, a panel discussion, and the screening of the documentary “1971.”

“Fifty years ago, we were criminals — and now we’re heroes,” said Bonnie Raines, 79. “Isn’t that the way history goes sometimes?”

The historical marker is the brainchild of Kevin Tustin, now the public information officer for Norristown, who stumbled onto this chapter in U.S. history while completing his master’s in criminal justice at West Chester University back in 2016.

As he navigated the web for a final class project, Tustin dived headfirst into the internet rabbit hole and rolled into a New York Times Retro video titled “The Greatest Heist You’ve Never Heard Of.”

“I was intrigued. I was not quite sure what it would be about, but within like the first 30 or 40 seconds of the video, it said something about the burglary of a small FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, and as someone who’s lived in Delco their whole life, you’re like, ‘Wait, that happened in Media, Pennsylvania?’ Like, you would never expect something like that would happen in essentially my backyard,” Tustin said.

He finished his assignment — but tucked away that information for later.

As it happened, at around the same time the Media burglars had begun to break their silence. They’ve probably told their story more times than they can count at this point, but they don’t mind giving it another go.

“I hope everybody who’s serious about social change spends some time with the history of other movements. We’re not the first people — whoever you define ‘we’ as — to try to change the world, and we won’t be the last,” Forsyth said. “But, you know, the people who’ve done things in the past, digging into the details of their successes and failures is really valuable.”

An activist couple

Like much of this country during the 1960s, Philadelphia was brimming with activist energy. The civil rights movement was beginning to secure major wins at the legislative level. Meanwhile, U.S. soldiers had just touched down in Vietnam — leading to antiwar protests at home.

Bonnie Raines’ activism began alongside her husband, John Raines, who died in 2017 at age 84. He was a part of the Freedom Rides and was subsequently jailed during confrontations with racist mobs. When she and John met, they were beginning to get more involved with the movement and worked on voter registration in the South, Bonnie told WHYY.

“After graduate school, we moved to the Germantown section of Philadelphia and were part of a community of protest against the war in Vietnam and against the draft. Philadelphia really was the center of all of that protest activity, and so we became part of that community of protest,” Raines said.

With a background in education, Bonnie juggled activism and working with children, while the couple simultaneously raised their own. Alongside a group of Catholic activists, the couple began breaking into draft boards in the middle of the night to remove and destroy files.

“Because at that time, the draft was a paper system, and if you destroyed the paper, you could disrupt the draft. And so our activism in Philadelphia began with a draft resistance movement, it was called,” Raines said.

In addition to their draft board actions, the couple organized protests and sent signed petitions to Congress. But the war continued to worsen and, Raines said, it became quite clear that the government was lying. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s fingerprints were all over the city, she said.

“Among all of that activity, he sent agents into surveillance … they infiltrated groups that were protesting the war, there were informants inside of the movement — and most of it unconstitutional and illegal … Hoover was very, very opposed to dissent of any kind, whether it was against the war, civil rights movement, or Black empowerment,” Raines said.

In office for 48 years until his death in 1972, Hoover was as durable a fixture as any in 20th-century government. Outside of the man holding the nuclear launch codes, Hoover’s influence on the country was arguably the most far-reaching.

His abuse of power and disregard for First Amendment rights often put him at odds with social movements. Raines believes that Hoover wanted them crushed even if it meant breaking the law to do so.

“But we had no way to really prove it and tell the truth about what was going on — except to think about one strategy, which was to target an FBI office that was in the suburbs, not the main government office in Center City, but a field office,” Raines said.

Forsyth’s picture day with the feds

Keith Forsyth was attending Wooster College in Ohio when he first “woke up” to the political realities of the United States. In his teenage years, Forsyth said, his interests were mainly girls and music. Thanks to a well-informed friend, he was introduced to reading material that redirected his train of thought.

“And once I realized the lies that were being told about that war and how evil it actually was, it sort of opened me up to questioning a lot of other stuff … and I became much more aware of all the shortcomings in our society,” Forsyth told WHYY.

He immediately pushed himself into the antiwar movement in his college town.

“And that was actually the first time I had my picture taken by the FBI — we were demonstrating in front of the local draft board,” he said.

By spring 1970, he had seen enough tragedy. The killings at Kent State and Jackson State universities shook him to his core. He decided to leave school and devote his life to the peace movement. But, Forsyth said, he didn’t feel as if he could accomplish that much while living in Ohio, so he hitchhiked all the way to Philadelphia.

Through connections here, he managed to secure an apartment and a job. Just 20 years old at the time, Forsyth got involved with Selective Service disruptions alongside the Catholic left.

That’s how he met the man who would be the mastermind of the Media FBI heist, William “Bill” Davidon.

The ‘Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI’

Davidon, who died in 2013, had a reputation for having “the chops” even before March 1971.

A physics and mathematics professor at Haverford College, he was active in the peace movement and was an unindicted co-conspirator in the Harrisburg Seven case, in which a group of nuns, priests, and a Pakistani American scholar, led by Father Philip Berrigan were accused of plotting to kidnap national security adviser Henry Kissinger “in an effort to end the Vietnam War.” Their trial ended in a hung jury.

One day, Davidon invited Forsyth on a walk so they could speak without fear of being overheard, because breaking into the FBI would surely raise some eyebrows.

“And, you know, I don’t really remember exactly what my initial reaction was, but I know I said yes very quickly,” Forsyth said. “Bill’s idea was that we would take their own internal documents and, relying on the habits of bureaucrats to keep records of everything, no matter how incriminating, that we would take those records and publicize them through the news media, and that would put the brakes on some of the FBI’s worst practices.”

The conversation transitioned to who should and should not be on the team. Candidates had to be dedicated, reliable, and humble, with the ability to keep quiet.

Obviously, Bonnie and John Raines were ideal candidates, but Davidon had a bit of trouble convincing the pair to join the operation.

“At first, we were a little taken aback at that suggestion,” Bonnie Raines said. “It seems pretty far out. But Bill — we had so much respect for him, and he wasn’t going to recommend something that was crazy. And so the small group of us who he asked to think about it began more and more to think that perhaps that was something that was doable. And so we began to plan for that, for that actual action, we call it.”

The eight-person team consisted of Bill Davidon, the Raineses, and Forsyth, as well as Bob Williamson, Ralph Daniel, Judi Feingold, and another who wished not to be named. They met and planned regularly in the attic of Bonnie and John’s house in Germantown. They began to case the FBI office and observe the patterns of the people around it.

‘I tried to disguise my appearance’

The FBI office was in a multi-use building at 1 Veterans Square in Media, right across the street from the Delaware County Courthouse, which meant there was always a guard nearby. And because the office was on the second floor of the building, which also happened to be used as apartments, someone was always inside. So planning had to be meticulous.

By February 1971, the group had the exterior patterns mapped out but still needed a peek inside. What was the alarm setup? What type of locks were on the doors? What was the office layout? Were the file cabinets locked?

A rather novel solution was devised.

“The way we were going to get that information was to assign me the role of calling the FBI office and saying that I was a student at Swarthmore College and I was doing research on opportunities for women in the FBI, and could I come in and interview the head of the office as part of my research,” Raines said.

The FBI bought the story, though one other problem needed to be addressed.

“I was 29 at the time,” Raines said, “but everybody said that I sort of looked kind of like a kid. So I tried to disguise my appearance as much as I could. I put my hair up inside of a winter hat and I wore glasses that I didn’t ordinarily wear and tried to look like a college student.”

The FBI agent never suspected a thing, she said — he didn’t even ask her name or notice that she never took off her gloves. As she interviewed him, Raines took note of a three-office layout, no alarms, standard locks on the doors, and unlocked file cabinets.

Her work was done. Now, the caper could begin.

Heist of the century

The night of March 8, 1971, was chosen for one reason: People would be watching the Fight of the Century.

Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier were set to square off for the heavyweight championship in a fight that seemed to symbolize the political hostilities of a country divided over the Vietnam War and race relations. Nearly everyone was tuned into the bout — providing optimal cover for the group in Media.

Dressed in their finest clothes, the self-styled Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI descended on the office in Media. Some were on getaway-car duty. Others were on surveillance duty. The 21-year-old Forsyth was assigned the job of lock pick.

“I went up to the building, went inside, and was prepared to pick the lock, which is something I was pretty good at at the time, and discovered that there was a change in the locks since the last time I had been in the building. Maybe a week to two weeks before, they had added a new lock that was not there before. And it was a type of lock that you would need special tools to pick, which I didn’t have,” Forsyth said.

Thrown for loop, he briefly wondered if there were a leak in the group. However, the thought soon left his mind. He retreated to a nearby hotel, where the group had set up a temporary headquarters, and reported that the door was a “no-go.” Someone then suggested a secondary door that was no longer in use in the office. The only problem was a rather large file cabinet blocking the door from the inside.

They decided to try anyway. Forsyth returned to the scene of the crime and picked the lock quite easily. He even managed to break the deadbolt off without being heard, thanks to the Ali-Frazier fight.

“The [building] manager was, indeed, listening to the fight on the radio, because I could hear it through the floor. So anyway, that provided some very welcome distraction,” Forsyth said.

He pushed the door but was soon met with the cabinet, which tipped forward slightly. He decided to back off and went to the car to get a jack. It made an “excellent crowbar” and allowed Forsyth to slowly move the cabinet away from the door. Once the door was open, Forsyth gave the all-clear for the inside crew to sweep the office.

In a March 2021 interview, Citizens’ Commission member Ralph Daniel told NPR’s Scott Simon about the operation to steal roughly 1,000 files from the office — many of them involving “peaceful antiwar activities,” civil rights groups, and women’s groups.

“We found a number of files on bank robbers. We left those. … We figured the FBI should keep working on those,” Daniel said. “But we took all the files that covered various people who were being investigated — a lot of Black Panthers, other Black groups that — civil rights groups and such. And we did, we ran across a document that later on became very, very important that documented a program called COINTELPRO.”

The group of four rushed out the office, suitcases of documents in hand. Out of the corner of their eyes, they noticed something terrifying that could threaten the whole mission: The guard across the street at the Delco courthouse appeared to be looking right at them through the glass door as they loaded the files into the trunk.

The guard didn’t seem to register what was happening, though.

“Our plan was then to go to a Quaker farm, a conference center [Fellowship Farm, in Pottstown] that was going to let us use a building at the farm to sort through the documents, which we started doing immediately that night, and it didn’t take very long to find some very incriminating documents,” Bonnie Raines told WHYY News.

Government surveillance was revealed in 60% of the documents, according to Raines. After photographing the most incriminating files, the group started the next phase of the plan.

“We sent them to three newspapers — three reporters … at the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times. And we also sent copies of the documents to two members of Congress,” Raines said.

But the two members of Congress sent their copies to the FBI. The Los Angeles Times and the New York Times returned their copies to the FBI without making them public (though they later did so).

Enter Betty Medsger, a reporter for the Washington Post, whom Bonnie and John Raines had known from her days as a reporter for the old Philadelphia Bulletin in the 1960s.

FBI agents ‘behind every mailbox’

Medsger was still a fresh face at the Washington Post, having joined the staff there in 1970, when an unusual set of about 14 photocopied documents arrived.

“When I received the first set of FBI files, the first file was the one that became sort of emblematic of the burglar’s files — a document that advised agents and informers to make people paranoid — that was their word. It said, ‘Behave in such a way that people will think there’s an FBI agent behind every mailbox,’” Medsger said.

Maybe it was a hoax, she thought. But the names of people under surveillance in Philadelphia were familiar to her, like pastor and advocate Paul Washington of North Philadelphia.

Now that she could kind of authenticate them, she read further.

“There were files that revealed that the FBI had hired as informers people who were working on the Swarthmore College campus … security office people, low-level administrators on the campus, and that they were like switchboard operators and were listening in on the phone calls of professors and some students and reporting that content to the FBI. And I also learned that every Black student on the campus of Swarthmore College was under surveillance by the FBI,” Medsger said.

Though some things were stated pretty explicitly, others left Medsger puzzled.

“One of the other very important things that came out of the Media files was something that was pretty mysterious at the time. There was one file that had in big block letters in the upper right-hand corner a single word: COINTELPRO. And we didn’t know at the time what that stood for or what it was,” Medsger said.

She had no idea who had sent her the files, but after a colleague helped verify that they were authentic with the FBI, she made the decision to protect the identity of her source and not hand over the documents to the authorities.

“The files that were stolen — that did happen three months before the Pentagon Papers were released to the New York Times first and then to the Washington Post. And so that meant that on that day that I received the files and was writing the story that Katherine Graham, the publisher of the paper, and as far as I’m concerned, the editor, never dealt with anything like this,” Medsger said.

She began writing her story.

The Nixon administration, via Attorney General John Mitchell, ordered Graham and Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee not to publish, and to relinquish the documents to the FBI.

Medsger thought the decision should have been an easy call to make. But Graham had a huge problem in front of her.

“I learned later she did not want to publish. And the attorney for the paper also urged them not to publish. And again, thanks to Ben Bradlee, it would happen later with the Pentagon Papers, and then even a year later with the beginning of Watergate, he made the case very strongly that this was important public information,” Medsger said.

Though the revelations would be embarrassing to the FBI, Bradlee argued that national security would not be sacrificed if the story were to run — and, in fact, that the country needed to know the bureau established to protect it was also spying on it.

At the last minute possible to print, 10 p.m., Graham gave the call to publish.

Much of the public was in a state of shock. The newspaper received some letters to the editor chastising it for the decision to publish government secrets, but those paled in comparison to the shift in public opinion over the FBI and Hoover, Medsger said.

Even Congress and the news media, which had been complicit in placing Hoover on a pedestal, changed their tone, she said.

“Just about everything that was written about the FBI and Hoover up until this time was praise of Hoover, praise of the FBI, because people simply didn’t know what was happening,” Medsger said.

Previously silent members of Congress called for an investigation into Hoover. Editorials calling for the same thing popped up in papers across the country, including the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Philadelphia Inquirer.

But by the end of April 1971, it became clear that no such thing would happen.

“There were stories that continued to come from the stolen files right up through the middle of May, and then a one month later, the Pentagon Papers arrived. And that also was a very difficult decision for the publisher to make. But I like to think that because of the very difficult time that she had back in March, deciding on whether to run FBI secrets, that it was an easier thing for her to say yes,” Medsger said.

Years passed and with the FBI files, the Pentagon Papers, and Watergate now in the minds of the country, Medsger started to see some movement at the government level in response to the crimes committed by intelligence agencies and officials. She pointed to the amendment of the Freedom of Information Act in 1974 that gave those seeking information more leeway in crafting a “perfect” request and expanded the definition of a government “agency.”

The FBI came under investigation by both houses of Congress in 1975, during the Church Committee Hearings. Prior to the Media burglary, there was no official oversight of intelligence agencies.

Out of those hearings came a 1976 report disclosing the CIA’s attempts at mind control and its plot to assassinate foreign leaders, as well as an explanation of the FBI’s infamous COINTELPRO operation, details of which were finally starting to come out after a federal judge forced the government’s hand.

Essentially, the FBI had systematically spied on members of the feminist, civil rights, environmentalist, Puerto Rican independence, and communist movements in the country.

Muhammad Ali was under surveillance by the FBI through that program for his close ties to the antiwar movement and the Nation of Islam.

The program also sought to discredit and at certain points neutralize “subversive” leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, along with many others, often with tragic results. Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton was killed in his sleep by law enforcement officials directly because of the program.

Having seen the files herself, Medsger said that while there were political criteria to the surveillance, “just being Black was enough” to land on the FBI’s radar.

“Law enforcement, including the FBI, repeatedly came back to those old ways in time of emergency, in a very big way after 9/11, when the old rules came into play and Muslims suffered as Black people have suffered before,” Medsger said.

Many of the COINTELPRO documents have not seen the light of day. But there has been a renewed push to have them released to the public.

“Over the years, I watched all of that happening from a distance and had an awareness of the impact of the burglary. And I noticed, also, that they were never caught by the FBI,” Medsger said.

Not so secret

After that night on the farm, the Media burglars vowed to keep their distance from one another and to keep their secret.

Even as a couple hundred FBI agents descended on Philadelphia, the group slipped under the radar. Some jumped off the grid entirely, while others returned to business as usual.

In the immediate aftermath of the burglary, Forsyth “couch-surfed.” He believed the team had a couple of advantages.

“One was, for the most part, people really did stick to the dictum of not telling anybody and not even their close friends,” Forsyth said. “Also, there was just too many suspects in the Philadelphia area. I mean, Philadelphia had a very strong peace movement.”

An FBI drawing of the mysterious young woman posing as a college student who had cased the office was circulated, but it was generic. Forsyth said he remembered young people in the movement who looked like the drawing being hassled quite a bit by federal authorities.

After laying low for a few days, he returned to his normal activities in the movement by participating in the 1971 May Day protests in Washington, D.C. He was even arrested soon after by the FBI as part of the so-called Camden 28 for raiding a draft board there.

By 1980, Forsyth was exhausted. He decided to get married and thought it was fair that his wife knew about his role in the Media burglary.

“She was like, ‘OK, whatever,’ you know. We knew each other pretty well by that point,” Forsyth said, then chuckled.

As his kids grew older in the 1990s, he told them. One of his friends had already figured it out after seeing Forsyth practice picking the lock before the Ali-Frazier fight, then disappearing for days afterward.

“He put two and two together, but we just never talked about it,” Forsyth said.

A dinner party to remember

John and Bonnie Raines continued with life as normal, raising their kids. John continued in his job as a professor of religion at Temple University, while Bonnie worked to change social policy for children as the director for children and parent advocacy organizations.

The statute of limitations that applied to the burglary had run out in 1976, but it wasn’t until the late 1980s that the couple broke the news over dinner to Medsger — then the head of the San Francisco State University journalism department — that they were the ones who had sent her the stolen FBI files.

“We weren’t real close friends, but we were friends. And we liked each other a lot, and had kept in touch occasionally. And this was the first time that we were going to see each other for many years. And so we had a lot to catch up on, they invited me to their home for dinner,” Medsger said.

As the youngest of the couple’s four children left the room after briefly entering to answer a question, John Raines cleverly slipped in the fact that it was important for her to know Medsger because she had previously gotten important information from them that the public needed to know.

“I was astounded. I waited until [their daughter] left the room. And I said, ‘Are you telling me that you were burglars at the FBI office?’ And they said, ‘Yes.’ And it was just an amazing moment, as you can imagine,” Medsger said.

With lots of questions on her mind, she spent hours talking to John and Bonnie Raines, going on into the “wee hours” of the next morning about the burglary.

Of course, she wanted to know what they had done and why, but Medsger was also curious how they gathered the courage to do it. At the time of the burglary, the couple had three young children. Some of the other burglars also had kids.

Eventually, she convinced members of the group to allow her to tell their story in a book that was published in 2014. Medsger, a founding member of the nonprofit Investigative Reporters and Editors, used her skills to sift through more than 34,000 pages of FBI files about the case and track down the remaining burglars.

A commemoration

Fast forward to 2018, when Kevin Tustin was talking to a friend about getting a historical marker on behalf of the Media burglars. She gave him the rundown on the process. Meanwhile, he immersed himself in what had already been put out there about the heist, from Medsger’s book to Johanna Hamilton’s documentary “1971.”

“I submitted my application, and in March 2019, the state approved. And then of course, 2020 happened,” Tustin said. “So cut to now, and we’re finally in the throes of getting the marker unveiled in Media and having some of the burglars get to come in attendance to see it. So even though I wanted it last year, it kind of seems very appropriate that the marker will be unveiled 50 years after the burglary happened, so it’s kind of a happy accident.”

This won’t be just any unveiling ceremony on Sept. 1. Starting at 4 p.m. outside the building at 1 Veterans Square, there will be speeches by officials, Medsger, Davidon’s daughter, and others. Once the marker is officially on view, the festivities will move inside to the second floor.

There, Medsger, Raines, and Forsyth will do a book signing. Then the celebration will move to the Media Theatre, where there will be a screening of Hamilton’s “1971” documentary followed by a live interview led by Marc Lamont Hill and featuring the burglars, Medsger, a former FBI agent, and civil rights attorney David Kairys.

Tickets for the book signing have sold out. Tickets for the screening and panel discussion can still be purchased here.

Tustin credited community member Stacy Olkowski, who contacted him out of the blue after the marker was approved, for bringing the commemoration events to life.

“She’s definitely someone I tipped my hat off to. She didn’t have to get involved. She didn’t have to do as much as she’s planning, but she’s taken the bull by the horn,” Tustin said.

It was Olkowski who suggested that Tustin bring Temple University’s Klein College of Media and Communication dean, David Boardman, into the fold. Boardman had also wanted to get a historic marker installed, but Tustin beat him to it.

Boardman described Medsger as a lifelong friend, and like her, he views the burglary as a monumental event in not only American history but journalism history. His involvement with the commemoration events did not require any arm-twisting.

“A lot of people here in Media and in Delaware County and in the Philadelphia region are not particularly aware of this. Maybe they’ve heard little snippets there, but they don’t really understand what a significant event in American history this was,” Boardman said.

To Medsger, having a marker dedicated to that day is a “beautiful thing.”

“I do think that it’s special and appropriate,” she said, “that there be a sign there that people honor, know how it came about, that one of the most important and powerful agencies of the federal government was forced to be accountable to the public, and to change as a result of this act of resistance by a group of local people who displayed a lot of courage.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.