How the pandemic has shrunk our worlds

We’re more cautious about people and places after the last 24 months. And for better or worse, some changes we’ve made seem likely to stick.

Listen 4:39

Judy Kozulak had her hair cut and styled for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic started by stylist Lorraine Keane at Perry Anthony Salon & Spa in Wilmington, Del., on March 14, 2022. Kouzulak is severely immunocompromised, and hasn’t been inside public spaces since 2020. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The world shut down two years ago, and suddenly the scope of many of our lives was wedged between the walls of our living rooms. Complex and three-dimensional relationships were flattened onto computer screens. For many, work became either a dangerous necessity or an intangible concept. And plans for family visits, classes, appointments, weddings, conferences all flushed down the tubes.

So much of the world was remote that it became easier, maybe as a survival tactic, to focus mainly on what was in front of us.

Those constraints lessened as pandemic restrictions lifted, vaccines became available, and coronavirus cases ebbed. But many of us have grown accustomed to the adjustments we made over the last 24 months. Our social circles have become tighter. We’ve become more politically polarized. We’ve become more cautious.

For some, that may represent a sad shift away from a utopian vision of a connected, diverse, and free America. But for others, it’s actually been kind of nice. What follows is a collection of pandemic habits and adaptations formed by people around the Philadelphia region that, for better or worse, these folks are confident will stick.

Knitting a safety net, because she didn’t have one

Judy Kozulak is among the most vulnerable to the threats of COVID-19. The 65-year-old Wilmington resident is immunocompromised, and spent much of the last two years feeling like she was hiding under a rock. Precisely because being limited to her own home has been so frustrating, she’s been compelled to find creative workarounds to stay healthy and sane.

Kozulak underwent major surgery in 2018. In the months afterward, she found herself watching a lot of TV, lazing around, losing strength. Normally very active and in good shape, she couldn’t walk around her condo building without being in pain. That was her state when the pandemic hit. Because she’s immunocompromised, she was serious about remaining housebound and isolated from anyone else. She found she was so bored, she had nothing to do but start building up her strength again.

“My stamina improved solely because I was stuck in the house and I couldn’t find any other distractions,” said Kozulak.

She increased her walking distance, bought a cheap exercise bike on Amazon, and eventually started working on a Pilates routine. She’s not sure how long it would have taken to get back into shape if it hadn’t been for the pandemic, but she credits it with her accelerated recovery and is excited to keep up her active lifestyle. Walking around outside is her only way of maintaining social interaction.

There are more mundane habits she’s developed that she’s certain will stick, like getting her groceries delivered. Dealing with a weakened immune system, Kozulak said she has always avoided shopping at peak hours, especially during flu season. She’s thrilled curbside delivery is a more mainstream service now, and will continue to use it indefinitely.

But Kozulak’s increased fear of crowded places will stick with her, too. Because she’s at such a high risk of serious complications from COVID, she said she won’t feel safe being out in the world until there is an adequate supply of antivirals and monoclonal antibody treatments that respond to whatever variant is circulating. In other words, a good mask is not enough. Not for her.

“Basically, I don’t have a safety net,” she said.

Still, spending six decades with the understanding that a common cold could be the end of you gives you a bit of practice at knitting your own safety net. Last week, Kozulak received her first shot of Evusheld, the first prophylactic treatment for COVID-19, reserved for those who are at high risk. She said she was thrilled. With her new layer of protection, she planned to get her first haircut in more than two years.

“I’ve been hacking away at the bangs,” said, laughing. “But the rest of it is pretty ugly.”

Coming to a political turning point

For some, the shrinking has been less about the physical world and more ideological.

Until the pandemic, Tony never had a set political ideology. WHYY News agreed to withhold his last name because he owns a small company and didn’t want his politics to affect business.

Tony voted Republican as a young man, but it was mostly by habit, he said, not because he was super politically engaged. He voted for Obama twice, then Trump. His political opinions straddle traditional party lines: He’s pro-choice, pro-gun, and most importantly, pro-business.

Tony is a partner in a small business in the automobile industry. At the beginning of the pandemic, Gov. Tom Wolf announced shutdowns across the commonwealth, including at car sale lots. Tony couldn’t believe it. Beyond not knowing how he’d keep his employees paid, it didn’t make any sense to him: Without public transportation, people needed cars now more than ever. He had one woman call him crying because she had totaled her car and had no way to get to her doctor’s appointments for her cancer treatment. No one was selling cars. That Wolf would make what he considered to be such a misguided rule, which few other governors did, was mind-boggling to him.

“He’s sending people away from the businesses in Pennsylvania to other states,” he said of Wolf.

For Tony, the COVID regulation policies enacted by Democratic governors were a sign of their animosity toward small business owners like himself. He pointed to more contradictions: Big box stores like Target were allowed to stay open because they sold food, but small hardware or toy stores were forced to lose business. It just didn’t add up for him.

Now, the 40-year-old Lansdale resident said, he will never vote for a Democrat again. He sees the pandemic as a blessing, revealing the true priorities of each political party.

“It opened up my eyes and the eyes of many people to see exactly where the Democrat Party stands,” he said. ”And they are not in any way supportive of small businesses.”

Tony said he’s lost some friends along the way, people who don’t see things the way he does. But he’s also gained some: people who were just as infuriated with the shutdowns as he was. New friends from Facebook groups he joined, and people who found creative ways to keep their businesses afloat amid the shutdowns. He recognizes that this means his social circles are more politically polarized, but he said he thinks in a lot of ways that’s been clarifying for him.

“If they’re not like-minded to me or they’re voting for, let’s say, the Democrat Party, they’re technically voting to hurt me,” he said.

Embracing the Fave Five

Pam Ramos remembers back when T-Mobile offered the Fave Five deal: free texts and calls to your five closest contacts, you choose which ones. That’s a perfect way to think about the way her social world has contracted since the pandemic, Ramos said — and she likes it.

For Ramos, 48, being forced to form a pod of very close friends and family has not been the loss of community she expected it might be at first. Instead, she’s found it to be an exercise in intimacy.

“It’s the capacity to care for three versus 12 people in my life and do it well at a smaller scale,” she said.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Ramos recalled, the conversations with her pod mates got pretty intense, even existential. They wondered if this would be how it would all end. That brought them closer, she said, and she wants to keep it that way.

She’s even extended the Fave Five rationale to her vacation schedule. Though she might normally go on a big group trip, she’s spending her time off on the beach in Puerto Rico with just one close friend, whom she’s known since high school.

Before the pandemic, Ramos said, she thought of herself as an extrovert, but now she’d say she’s developing as an introvert.

“Solitude is something that maybe a lot of us learned to do better, even if we don’t like it,” she said.

Opting for fewer germs, but a lot more laundry

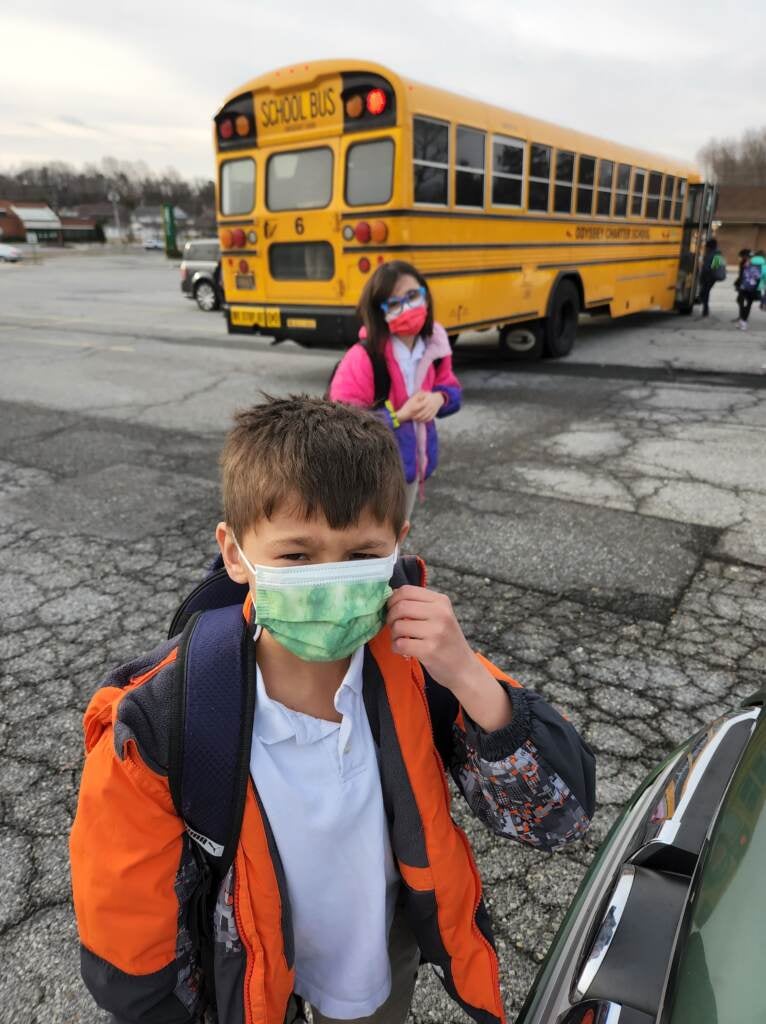

For Chris Anderson of Wilmington, the smallness has come in the form of a bubble. At the beginning of the pandemic, Anderson and wife Jessica were spraying down everything that came into their house: their groceries, packages left at the door, even their kids.

“At first, we were giving them a full bath, right away,” he said of his four children, who range in age from 3 to 9. As the pandemic progressed and everyone learned more about how the virus was spread through air particles and not on surfaces, Anderson said they stopped so much sanitizing. But stripping the kids down and changing their clothes immediately when they come home from school is a habit that has stuck.

(Courtesy of Chris Anderson)

“It’s very easy for sicknesses to spread throughout school, not just COVID,” said Anderson. “The preschool kids, they’re on the floor crawling around and playing on the playground equipment, sharing everything with each other. And so we just feel like that and the germs could be on their clothes and their hands.”

Anderson said they’ve kept it up, in part, because it seems to have worked: Their family of six has only gotten minor colds since the pandemic started. No one has contracted COVID.

The only thing that might stop him from switching out the kids’ clothes upon entry to the house is all the laundry it creates. Sometimes, they’re running two loads daily.

“Multiple outfits each day, that adds up,” he said.

Feeling ‘cheated’ by the loss of spontaneity

When Renee MacKenzie retired at 65, she imagined she had at least a decade of adventures ahead of her before her body started to slow her down. She envisioned cruises, travel, plays, theater. A spontaneity that her work schedule had never allowed for: She could just grab her keys and take off if she felt like it.

The retired therapist snuck a few years of that in before the pandemic hit. But it’s been hard for her to adjust to the reality that the pandemic has taken at least two of her healthy retirement years.

“I feel cheated,” said MacKenzie, now 72.

“Even as I say those words out loud, there’s that little twinge of guilt,” she said, acknowledging that overall she’s had it easy compared to so many others.

(courtesy of Renee MacKenzie)

Still, she gives herself permission to feel disappointed that the trip she’d planned to Alaska with her kids and grandkids may never happen now. By the time she feels comfortable traveling again, her body will be a few years worse for wear. She has plans to see a show in the city in the coming weeks, but she’s trepidatious.

“There’s a push-pull right now,” she said. “There’s a sense of why don’t you sort of, like, gulp down everything that we haven’t done? On the other side of that, still a real cautiousness.”

Even if she does ease back into some activities, it won’t be with the abandon she’d once approached retirement with. Every decision will be calculated cautiously, carefully.

MacKenzie suspects the spontaneity will never completely return.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)