How Philadelphia renders Black history invisible

But before 1990, there were only two markers associated with African American history installed in Philadelphia.

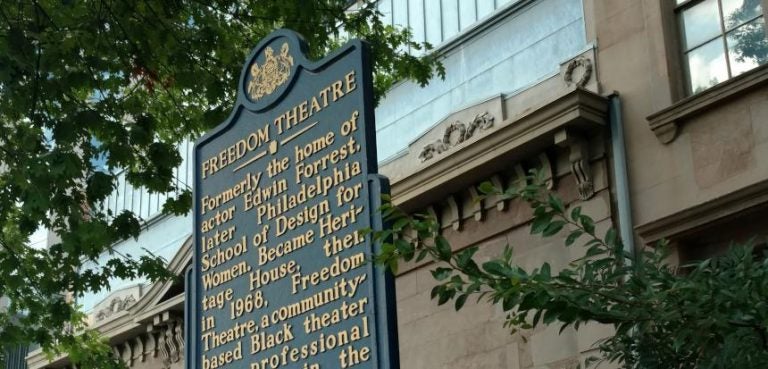

Freedom Theater is located on North Broad Street. (Jake Blumgart/PlanPhilly)

Philadelphia’s streets are lined with history. The blue and gold signs issued by the Pennsylvania Historical Museum and Commission mark everything from the oldest medical library in the U.S. at Pennsylvania Hospital to 300-year-old Elfreth’s Alley.

But before 1990, there were only two markers associated with African American history installed in Philadelphia: First Protest Against Slavery (1983) and St. Thomas’ African Episcopal Church (1984). To fill the gaping hole in the American story, in 1990 Charles L. Blockson, founder and then-curator of Temple University’s Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, launched the historical marker project. The project was funded by a grant from the William Penn Foundation. In the introduction to Philadelphia Guide: African-American State Historical Markers published in 1992, Bernard C. Watson, Ph.D., then-president and CEO of the foundation, wrote: “The Philadelphia African-American Pennsylvania State Marker Project is a modest first step toward correcting one of the most egregious problems in Philadelphia public history. Philadelphia, the birthplace of our independence, home of the Liberty Bell, the first capital city of these United States, is so rich in historical detail that the absence of signs and signposts to recognize and commemorate the nearly 300-year presence of Africans and then African-Americans, has been especially troublesome. They, too, were and are part of our history.”

Then as now, gentrification was unmarking black history. Dr. Blockson wrote this about the origin of the project: “When the project began, it became apparent that Philadelphia, like other American cities, was losing places of historical significance through gentrification and neglect. It is our hope that through the installation of the African-American historical markers, we can preserve the remaining sites and revive memories of past events and citizens who lived before us and made positive contributions to our nation.”

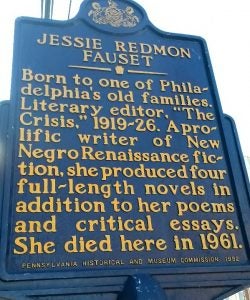

Jessie Redmon Fauset was among the first wave of markers dedicated in the 1990s. Her marker was installed in front of the North Philadelphia house in which she was living at the time of her death.

The February 18, 2017 issue of the New Yorker included an article by literary commentator Morgan Jerkins, “The Forgotten Work of Jessie Redmon Fauset.” The piece revived interest in Fauset’s literary work. However, the accomplished writer was never forgotten in Philadelphia. On its 150th anniversary in 1998, the Alumnae Association of the Philadelphia High School for Girls elected Fauset to their Distinguished Daughters Court of Honor. She was the first African American graduate of the prestigious public school.

Although former Sixer and NBA legend Charles Barkley played on a different court, he, too, honored Fauset by naming her a “Philadelphia Black History Month All Star” in February 2018. A few months later, Jacqueline Wiggins found an ugly patch on the sidewalk where Fauset’s historical marker used to be.

Wiggins is a community activist, tour operator and former member of the Pennsylvania Historical Museum and Commission (PHMC) Black History Advisory Committee. In preparation for a church tour of North Philadelphia, she mapped her points of interest. Wiggins told me how she felt when she realized Fauset’s marker was missing: “At first, I thought maybe the marker had been taken down by PHMC for cleaning. I had been concerned about the markers for James Forten, Julian Abele and Paul Robeson when I couldn’t find them a few years ago only to have my worst fears (theft or dismantling) eased in finding out that PHMC takes down markers for cleaning from time to time.

I asked a longtime community activist if she knew anything about the Fauset marker. Her immediate response was, ‘Check to see if the pole that holds the marker is gone, too.’ Traffic was behind us, so I circled back, and, yes, the pole was missing. I began to panic a bit. Having neither marker nor pole had to be very unusual. Where was it? Had a mistake been made about Fauset having lived at 1853 N. 17th Street?

Sadly, Jackie’s panic was justified. Fauset’s missing marker went unnoticed because longtime residents have been displaced. The block is now mostly student housing. The current residents would not know what was there before they moved in.

On April 1, 2013, 1853 N. 17th Street LLC received an L&I permit for the complete demolition of an existing structure and erection of an attached structure. The LLC was issued a rental license on May 22, 2013; Ahmed Alhadad was the contact person. Alhadad is a principal owner of Temple Villas LLC. Google images show Fauset’s marker was there in June 2012. By September 2014, it was gone. Neither PHMC nor the Streets Department was aware the marker and pole had been removed. Although their identities are shielded behind LLCs, corporate databases lead to Temple Villas as, well, the villain.

There is growing concern about the impact of gentrification in historically black neighborhoods. Just to be clear, no one is suggesting “Black Only” areas. The concern is that developers are erasing our history from public spaces. Wiggins said: “Things are happening so fast in the neighborhood due to intentional gentrification with buildings being torn down and newer structures going up. Family and neighborhood memories are being erased like never before.”

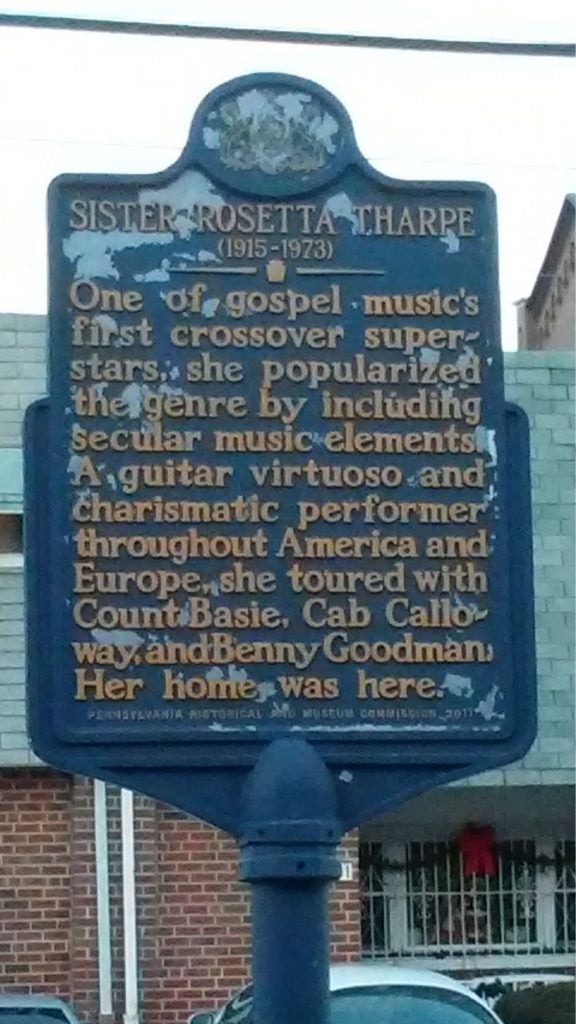

In the course of my research, I discovered that four African American historical markers have disappeared. PHMC’s database shows two are missing; the agency was unaware that Jessie Redmon Fauset’s marker had been taken down. This raises the question: How many other markers have been lost in the chaos of gentrification? PHMC told me via Twitter that they do not have the resources to replace missing markers. In contrast, the agency is responsible for maintaining a marker once installed. So I also notified them the marker honoring Sister Rosetta Tharpe was in need of repair.

The former Yorktown resident was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame last year. I am happy to report the gospel pioneer’s marker will be “refurbished” by June 2019. A reader might ask why a missing or damaged marker matters. There is power in memorialization. The blue-and-gold markers matter because black history matters. As the nation gears up to commemorate 400 years of African American history, the story of slavery, emancipation, struggle for civil rights, and achievements in all fields cannot be told without Philadelphia. In a July 2018 conversation with former WURD program director Stephanie Renée, Dr. Blockson admonished African Americans “to collect, preserve and disseminate our history. … Hold on to your ancestors. You don’t know who you are unless you honor the ancestors.” In the coming days, community members will be the eyes on the street. They will check on the historical markers in their neighborhood and share their status via Avenging The Ancestors Coalition’s Facebook group or using the hashtag #400YearsPHL on Twitter. The ancestors have already done the heavy lifting. It is our responsibility to preserve their stories of faith, resistance and triumph for current and future generations.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.