Hospital visits to those who are ill but not dying are vital too, clergy argue

When the pandemic began, many hospitals strictly restricted visitors. At some, faith leaders have been limited to phone calls and video chats ever since.

Listen 2:33

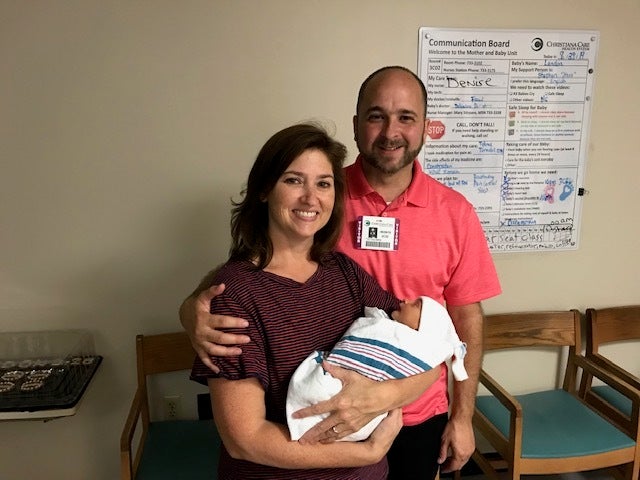

Since hospitals have restricted minister visits due to COVID-19, Pastor Paul Shirley of Grace Community Church has reached out to patients on the phone. (Courtesy of Rebecca Shirley)

Becky Cahall said she felt afraid and isolated during the 17 days she spent in the hospital in June and July because of a blood infection.

“It was pretty scary, because they’re telling you, ‘This could kill you,’ and it did affect my heart, so there were some very stressful and trying days,” she said.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, she wasn’t allowed visitors while she was a patient at ChristianaCare’s Christiana Hospital in Newark, Delaware. Cahall, 48, who lives in Elkton, Maryland, was particularly disappointed to learn she couldn’t see her pastor, Tobe Witmer of Lighthouse Baptist Church in Newark.

Though ChristianaCare does have its own staff of professional chaplains, Cahall said she wanted to see a familiar face.

“He has been there for me before. He’s cried with me, he’s prayed with me, he’s read the Bible to me. That means a lot,” she said.

“All I saw was nurses, doctors, and techs. It was awfully quiet there. It wasn’t a good experience at all, because I couldn’t see my relatives and I couldn’t see my pastor,” Cahall said. “The nurses did the best they could, but they had other patients to take care of — and that’s where I think a pastor would be able to help.”

ChristianaCare is one of several health systems in the region that allow faith leaders to visit hospitalized congregants for end-of-life care only, while their pandemic rules prohibit clergy from visiting patients who are expected to recover.

Other health systems in the region, such as Temple Health in Philadelphia and Virtua Health in New Jersey, have less stringent rules for visitation by faith leaders, though Temple allows it only for patients who do not have COVID-19.

Witmer said that faith leaders are like family to their congregants, and that allowing minister visits provides comfort and healing to patients. He believes that hospitals should be more flexible, and that the restrictions infringe upon religious rights.

“I felt like I was not being allowed to practice my calling as a shepherd, as a spiritual pastor of people. I felt like I was being hindered and prohibited from doing that,” he said.

Setting limits in different ways

When the coronavirus pandemic hit the United States in March, hospitals quickly put plans into place to protect their patients, staff and the community. Many hospitals severely restricted visitors — at some of them, loved ones, friends and faith leaders have been limited to phone calls and video chats ever since.

“We follow the guidelines of our public health officials, including the CDC, and we have a great infection prevention department that helps guide us in that direction. It’s for patient safety, as well as the safety of our community. We want to decrease traffic as much as possible so we aren’t inadvertently carrying in the virus,” said Tim Rodden, director of pastoral services for ChristianaCare.

“We’re in extraordinary times with COVID-19,” Rodden said, “and things are not the same as they were pre-COVID. None of us were looking forward to this, expecting this, and we’ve had to make drastic changes to the ways we operate in the community, in the hospital, in our houses of worship. So we’re providing the safest possible interactions with all the people we come into contact with.”

Like ChristianaCare, Cooper University Health Care in New Jersey and Beebe Healthcare in Delaware also do not permit clergy visitation, with the exception of end-of-life care.

“Beebe Healthcare’s chaplains are coordinating with local clergy to provide support to our patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the request of community colleagues, the chaplains are making direct visits as well as coordinating clergy phone and video visits,” a Beebe spokesman said in an email.

Other hospital systems are less restrictive, however. Bayhealth in Delaware permits faith leaders to visit with their parishioners, as coordinated by the hospital’s pastoral care team.

“All faith leaders entering a Bayhealth facility are escorted by a member of our pastoral care team and undergo our standardized screening process,” a Bayhealth spokeswoman said in an email.

Patients at Virtua Health in New Jersey, at Temple University Hospital, and at Temple Health’s Jeanes and Episcopal hospital campuses in Philadelphia are permitted one support person, who could be a faith leader. At Temple, this policy is limited to non-COVID patients.

Temple Health provides visitors with face masks, conducts temperature checks and asks screening questions before they enter buildings.

“There are so many things to consider when thinking about visitor management during the COVID-19 pandemic, as a health care entity we need to strike a balance between maintaining a safe work environment for patients and staff and also providing a mechanism for families and support persons to adequately support their loved ones,” said Dwight McBee, chief experience officer for Temple University Health System.

“These are incredible, challenging times for all parties, for health care entities, for patients and for loved ones, and for faith leaders as well, who want to see their congregants,” McBee said. “We are trying to strike a balance that works for all parties, knowing that at some point you get things right and at other points you need to take a step back and think through the challenge differently.”

He said the health system chose to allow non-COVID patients a support person to alleviate the stress cultivated during the pandemic and anxieties about being in the hospital.

“If you’re dealing with a health issue, whether it’s an emergent issue or a chronic issue, there’s anxieties associated with that. There’s anxieties associated with the unknown with COVID, ‘Do I have it?’ ‘Could I potentially get sick from another patient?’ And there’s also anxieties of not having someone with them. So with that, we eliminate one of those anxieties when we allow very specific scenarios that [permit a] support person to be at the bedside,” McBee said.

Temple’s hospital chaplains also support staff and patients who don’t have access to their spiritual support network, and leverage virtual meetings and phone calls with loved ones and faith leaders.

COVID-19 patients cannot have visitors, with the exception of end-of-life care, for which Temple allows one family member.

Jefferson Health also allows religious leaders to visit non-COVID patients across its regional facilities. For COVID patients, permission is granted for visitors in end-of-life situations, but with full personal protection equipment.

Sandra Brown, pastor of Peace Lutheran Church in Bensalem, said she felt very safe visiting three congregants over the past few weeks at Abington Jefferson Health and Jefferson Torresdale Hospital.

Only one person was allowed in the room at a time, and she was required to wear a mask and answer screening questions.

Brown said her visits were therapeutic for the patients because she provides an extra set of ears. In-person visits are more personal, she said; phone calls are usually shorter and may come with distractions.

“Adults tend to share different things with their pastor, and things they don’t share with their adult children,” Brown said.

Still, she said she understands why some hospitals do not allow faith leaders to visit patients.

“One of the hardest parts of ministry is not being able to visit your folks in the hospital, but at the same token, I’m very clear on the fact that safety is first. We’ve got to be able to be safe and the safety of the folks in the hospital is first. So if the pastor can’t come in, it’s OK,” Brown said.

“If anything I would rather them allow one family member in, so folks don’t feel like they’re all by themselves. But I also recognize clearly hospitals have to do what they have to do, and I’d rather them be safe than say, ‘Oh yes, we’ll let clergy in.’”

Offering a more personal touch

Rev. Dr. Vernon Ross of Bethel Community Church of Pottstown said some of his congregants have stayed at hospitals that do not allow minister visits.

He said he would like hospitals to find a way to permit faith visits because seeing a person’s face has more impact. Ross noted that he has not even been able to video chat with his hospitalized congregants, and only was able to provide information to the hospital chaplain.

“I believe someone I have been ministering to will feel more comfortable sharing what’s going on, what messages I need to relay back to their family and other members of the church. And it gives me an opportunity, based on my personal knowledge of them — I can minister because I know them,” he said.

“The only information I tell the chaplain is, ‘I have a patient in room 6-0-whatever, and I would love for you to go there and pray with them.’ Well, that chaplain doesn’t have any insight into that person’s life, that person’s ministries they serve in. If it was a choir member, I can say, ‘The choir is doing very well, rehearsals are going great,’ or, ‘The choir is off for the summer.’ I can have some very in-depth conversations with congregants that chaplains can’t.’

Rev. G. Dennis Gill, rector of the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, said visiting hospitals for end-of-life care during the pandemic has been a positive experience. Usually, he said, priests only visit patients expected to recover if there’s a request.

“Typically, the person who requests the visit is someone who’s had a very active faith life and understands and appreciates the needs of the sacraments in their life, especially penance, anointing, Holy Communion,” Gill said. “I think it’s been a great spiritual lift to them, and also it’s given them a sense of peace and calm in the midst of a very fluid and difficult time.”

Though he believes it’s critical that priests are able to visit congregants in hospital at the end of their lives, because physical presence is an important part of the encounter with the Lord, he understands why some hospitals restrict visits for those expected to recover.

“They need to be cautious about people coming and going … and I would really trust the hospital in those instances,” Gill said.

Sheikh Amin Abdul Aziz, director of Islamic pastoral care for Majlis Ash Shura of Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley, has provided spiritual care to patients at PennMedicine and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for the past 20 years.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, he’s provided that care over the phone. Aziz said he relates the prayer in English to the director of pastoral care, who then passes the information to the nurse or doctor to tell the patient in person.

During Ramadan, sick patients still wanted to participate in the tradition of fasting, he said. But if a person can’t fast because of illness, that person can feed someone else each day. So Aziz has been easing the burden of patients by feeding members of the community.

Though caring for patients remotely is not the same as in-person visits, he said it still touches the patients. Aziz does not believe hospitals should loosen restrictions.

“I think we should follow the same protocol as everyone else, because we don’t want to be so gung-ho religiously that we carry the virus through the hospital systems and back to our mosques or churches and back to our home. We want to be as responsible as everyone else,” he said.

Pastor Witmer, on the other hand, said he would be willing to take any protective steps possible, such as wearing PPE or getting tested for the virus in order to see his congregants.

“I would wear a bubble,” he said.

Chaplains vs. community faith leaders

ChristianaCare says it won’t ease its restrictions out of an abundance of caution, noting that it has had a group of professional chaplains who have been on site every day since the pandemic began.

“We take the spiritual care and emotional care of our patients, their families, and our employees very seriously. We partner really well with our community faith leaders to be able to provide connections to their members when they’re not able to visit,” Rodden said.

Paul Shirley, pastor of Grace Community Church in New Castle, said he, too, would like to visit his congregants in the hospital. He said religious patients prefer to meet their own faith leaders, because they’ve developed relationships with them that chaplains have not.

“Some of our older folks, I’ve known them for a while, and maybe I’ve seen their spouse die and go to be with the Lord. And now they’re hurting and suffering, and I’ve already walked through suffering with them before, and there’s some comfort in that,” Shirley said.

He also argued that chaplains can’t personalize care to patients’ various religions.

“To have their own pastor in this case be able to come to them, they’re going to hear words that are comforting to them and in line to what they believe when they need it the most,” Shirley said.

ChristianaCare’s Rodden argued, however, that chaplains are trained to cater care to patients’ individual needs. He said his health system’s chaplains ask patients and their families for information about what has comforted them in the past, and also seek their faith leaders’ input.

“‘What would you be doing now if you were visiting your member?’ ‘How can we help you with that to make that connection?’” Rodden said. “We put our own personal agenda aside, assess the specific spiritual need of that patient and family, and help to provide that support in the best way possible.”

Innovation is critical in these times, Rodden said, and the hospital has found creative ways to make connections between patients and their ministers, such as using tablets for video chats.

Witmer and Shirley say using technology does not have the same impact.

“Frequently, it’s older patients who struggle with the technology to Zoom or FaceTime, or they struggle with hearing over the phone, which creates a barrier to minister to them,” Shirley said.

“The physical presence with someone makes a difference. It makes listening to them more effective, and gives them the opportunity to hear what you’re saying more effectively. And, it provides a level of encouragement that exceeds whatever I could as a pastor over the phone — we’re doing that, I’m on the phone with members of my congregation in a number of different contexts, and I’m thankful for that — but I think it would add to their overall care if they were able to receive in-person spiritual care,” he said.

One of Witmer’s congregants, Bob Rockey, 78, of Newark, said talking to his pastor over the phone during his hospital stay for bacterial pneumonia presented challenges, because he wears hearing aids and has a flip phone. Seeing Witmer would have made his experience less isolating, he said.

“It’s almost like your dad talking to you, even though he’s younger than me. It would have been nice for him to be there, and we could have talked and had prayer together,” Rockey said.

His wife, Fran, 74, said she called the nursing station every day for updates on her husband, but the interaction did not feel personal.

“I would have felt more comfortable about his stay if Pastor Tobe had gone in to see him; ‘He’s really still sick, but we prayed together.’ You don’t hear that from the nurse. They just say, ‘He had a pretty good night, and his temperature is more normal,’” she said. “I know they’re dealing with this COVID and I understand their concern, but there are people who are suffering in other ways.”

Shirley said he would like hospitals to invite pastors and religious leaders into the conversation about how to provide spiritual care while also respecting health and safety policies.

“Obviously, I understand why that policy came to be, and especially at the beginning of this entire crisis, trying to manage everything and understand the virus, and trying to ensure the care of the patients and the community,” he said. “But I think it’s important for us to remember patients have spiritual needs as well as physical needs. And for many generations, our society has seen the benefit of allowing patients to receive that spiritual, emotional care at the same time as their physical care.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)