For children in the city, how loud is too loud?

Being aware of noise in your child’s environment is important for hearing and cognitive development, studies show. Apps can help identify quiet spaces.

Listen 4:00

(hemvala/BigStock)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

In and around Philadelphia these days, finding a quiet place can seem harder and harder. There’s traffic noise and construction noise. Restaurants are loud. Shopping malls are loud.

To help find places that aren’t set to high volume, Antonella Radicchi developed a free app called Hush City. She’s an architect and urban planner who has dedicated her career to reducing noise pollution in the world’s biggest cities.

“We have been told that because we live in cities. It’s normal that cities are noisy. This is not true,” said Radicchi. “The more you are aware of the sounds of the environment, the more you can start to reclaim good sonic quality over your environment.”

“That’s the message I want people to get,” said Arline Bronzaft, a psychologist and co-author of “Why Noise Matters.” Prolonged exposure to unsafe noise levels can cause cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, she said, and can significantly affect cognitive learning — especially in children.

“If you’re intruded upon by noise, your body is working hard to try to cope with it,” Bronzaft said.

And because a child is still developing, it’s harder for that young body to fight off the effects noise pollution can have.

Bronzaft was one of the first to discover this. In the 1970s in New York City, she was giving a lecture in an environmental psychology course about noise as a pollutant when a student got her attention.

“[She] raised her hand and said she wanted to speak to me after class,” Bronzaft said. A group of parents were concerned about the elevated train tracks next to their children’s school and needed help collecting evidence to possibly sue the school.

“So I went to the principal of that school and asked to look at the reading scores of children in the lower grades up until sixth grade in classes exposed to the elevated train noise, which was coming in about every 4½ minutes.” Bronzaft said. “And I compared their reading scores to the children on the quiet side of the building. And by the sixth grade, the children were about a year behind in reading.”

Those findings were published in a scientific journal, where they gained a lot of traction. Then, through a series of remarkable events, the city of New York worked with the transit authority to correct the problem. Part of the city’s efforts included placing acoustical tiles in the ceilings, as well as pads on the tracks to help dampen the noise of the train.

A few years later, Bronzaft was asked to do it again. “And so I … did the second study when the rooms were quieter and compared the reading scores from both sides of the building. And the children were reading at the same level.”

Her study has since been replicated a number of times, enough to conclusively say that not only can repeated exposure to loud noises put children at risk for hearing loss, it can also affect their cognitive development.

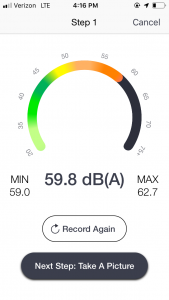

According to Bronzaft, unsafe levels of sound are around 85 decibels or above, something a subway train near a school could exceed without proper acoustical treatment. To compare, normal conversation is around 60 decibels, and city noise hovers around 75. A concert? Around 120 decibels.

Most importantly, Bronzaft said, to create lasting damage to hearing or our children’s cognitive development, it matters not only how much, but also how long the unsafe exposure is. That’s why awareness is everything.

“First of all, you have to know there’s a problem,” she said.

In the 1970s, when Bronzaft first did her research on the effects of noise on schoolchildren, experts from New York City came in to study the noise levels in the building.

Now, doing that can be as easy as pulling out your smartphone.

Using the Hush City app, it was relatively easy to find a quiet place in Philadelphia. It’s a little park, tucked away from the busy streets, with vines growing up the facades and a nice fountain. According to the app, this spot rated well under safe levels of noise exposure. The water provided a nice contrast to the city’s sounds. People were having conversations, reading books, eating lunch.

These days, there are a plenty of apps that can measure the noise around us. App creator Radicchi said that by allowing people to share their findings, she hopes her app can help empower them to take a bit more control over their noisy cities — to connect with one another and collectively find ways, for themselves and their children, to step away from the noise.

“Reflecting on the quality of your environment,” she said, “can be really something revolutionary.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.