Feminist Art Project explores what it means to fear or embrace the natural world

The gallery space is small and the name is long—the Mary H. Dana Women Artists Series Galleries at the Mabel Smith Douglass Library at Rutgers University—but the exhibits envelope the visitor with humanity and humor. The Feminist Art Project (TFAP) is celebrating its 10-year anniversary here with TFAP@TEN, on view through April 8.

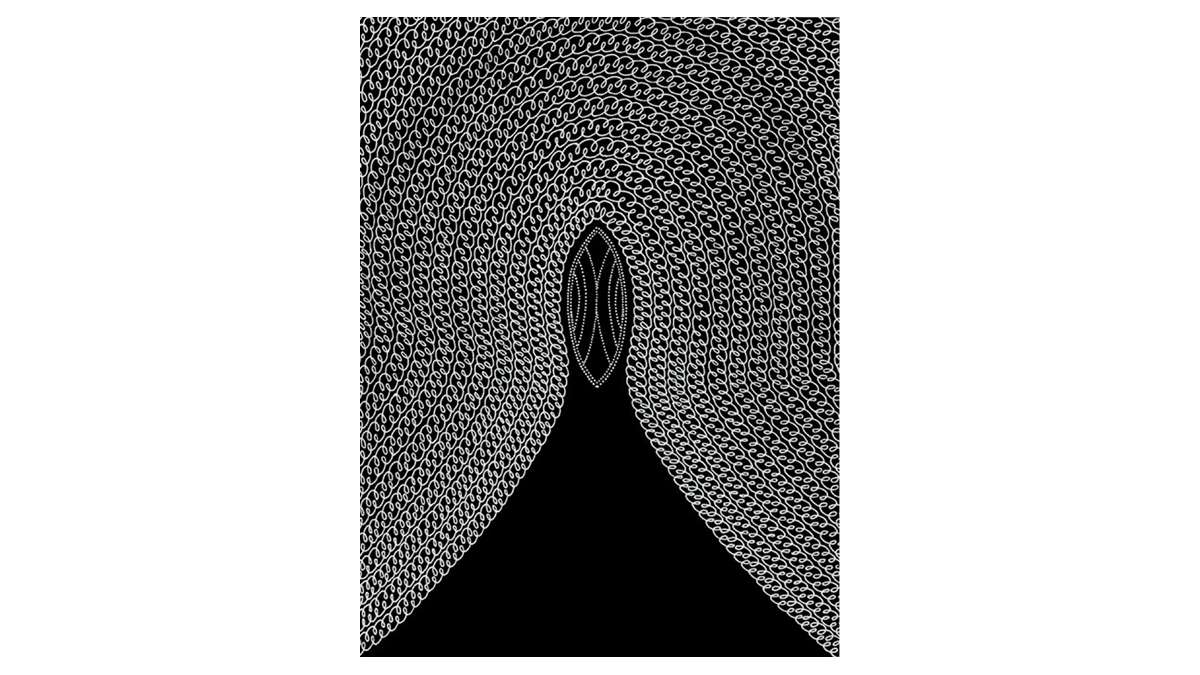

Entering the gallery to the right, we see a silhouetted female figure surrounded by flying sprites with the lightness of butterflies. This is Anonda Bell’s “Apiphobia (Biophobia Series).” But these winged creatures are bees, whose sting may evoke fear. The silhouetted woman, an earth mother, seems to be a divine spirit, summoning them. On inspection, we see the bees are paper cut outs painted in numerous patterns of yellow and black—no two repeat. Though cut from the same “cloth,” each creature the earth mother welcomes is unique.

The earth mother herself seems to embody nature—there are silhouettes of tree branches and honeycombs in her darkened form. And then there’s the title of the artwork, suggesting fear of bees—surprising, since this figure appears to be in harmony with the honey makers.

Perhaps the best way to overcome a fear of bees is to embrace them. And for an artist, finding the beauty in the patterns and colors that comprise these pollinators can help do that.

Biophobia is defined as a fear of nature. Bell, an Australian-born artist, says biophobia “is a seemingly inevitable consequence of growing up in an urban environment where our interactions with nature may be limited to incidental encounters, strictly mediated and moderated by the perspective or urban planners.”

On an adjacent wall, works by Jaz Graf embrace nature. “Night Soldier” is a moth whose beautiful feathers look like the dress of a fairy. The long proboscis of a humming bird leads the rest of its being in “Gaze.” Graf’s father, fascinated by hummingbirds, would watch them for hours, and by drawing the object of his gaze, the artist hoped to get closer to him, working through her emotions toward him and the silence in their relationship.

In the opposite gallery is an installation by Babs Reingold, like a stage set within a stage set. It starts with a graphite on paper, “Study for Luna Window: Ladder No. 6.” This framed work on the wall is intriguing enough in of itself, depicting a room in which some kind of platform is suspended and a ladder, bent and flowing, penetrates it, almost like a tree with roots in the ground. On the floor is a strange looking animal, keeled over, not far from an overturned basket, from which perhaps he imbibed too much.

On this drawing, or study, we see the rounded page corners on the right and the straight edge on the left where it was torn from a sketchbook. Three dates at the lower left indicate the three days in 2009 on which it was created.

Now, step back, and you are within that very room in the study. Variations have occurred. The suspended platform is now two windows on the wall, and the ladder—now a twin set of rungs—pierces the broken glass. Made of a felted wool, the hairy ladder has veins and tendrils, as if it is a living thing, or the remains of a living thing. Human hair seems to grow out of it. The ladder alone is captivating in how it combines traditional women’s craft (sewing, felting) with conceptual art.

The “Luna” in the title of Reingold’s work refers to Luna Park, the early 20th century Coney Island amusement park that burned in a fire and was replaced by a housing project. Having grown up in a housing project, Reingold has sad memories of broken windows and rickety ladders that, covered with dust, dirt and mold, revert to earthlike structures with roots.

So Yoon Lym is perhaps best known for her detailed, photorealistic drawings of corn row patterns on African American scalps, based on photos she has made of students and strangers in Paterson, where she lives. Born in Seoul, she spent her early childhood in Kenya and Uganda before moving to New Jersey at age 7. As a teenager Lym moved to Normandy, France, to study under exiled Korean painter Ung No Lee, who had a major influence on her.

From 2011 Lym did a series of monotypes, “Bloodlines,” suggestive of her own mixed bloodlines, a sort of anthropological study of Paterson. The artist sees her home of more than a decade as “a city of nomad refugees” like herself. Intertwining wavy lines of white, pink, and red suggest the complex passages of immigrants as well as their intermixed bloodlines and DNA strands.

“The wide range of the subject matter, materials and techniques employed in these artworks demonstrate a striking multiplicity of expression within feminist artistic practice today,” says Midori Yoshomoto in the catalog essay. “Their out-of-the-box approach, both in terms of concept and execution, transport the viewer into new worlds and inspire us to think a little more deeply about the world around us and within us.”

The Mary H. Dana Women Artists Series Galleries are located in the Mabel Smith Douglass Library (8 Chapel Drive, New Brunswick). Gallery hours are Monday through Friday, 9 a.m.-4:30 p.m. feministartproject.rutgers.edu

_______________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.