‘Essential’ and unsafe: Frontline workers of color face compounded risks

COVID-19 doesn’t discriminate when it infects. But some 'racialized patterns’ emerge as the pandemic widens.

A person wearing protective masks due to coronavirus concerns walks in Philadelphia, Thursday, April 2, 2020. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

As legions of Philadelphians have been laid off or forced to work from their living rooms, Ashley Jimenez, the director of case management at two homeless shelters, has kept coming into work.

She worries constantly about her clients, even more than usual. They are disproportionately elderly and afflicted with immune-compromising illnesses like HIV/AIDS.

“This is a population who are … more susceptible to the COVID-19,” said Jimenez. “When I walk in those doors every day, I’m thinking, and it kind of goes two ways: How susceptible am I to them? And how susceptible are they to me?”

Recently, an older woman staying at the shelter was struggling to sign up for unemployment benefits on her phone. Even though social distancing protocols are in place, Jimenez went to her aid.

“I could not do it and just say, ‘I’m sorry,’ or I could sit with her and help her,” said Jimenez. “I made the choice to allow her into my office and completed it with her. Those are the type of choices that our staff across the board is making.”

Each day, all workers deemed “essential” take a risk: They put their health on the line to keep Philadelphia running. And they’re not just doctors and nurses and firefighters — they are also janitors, home health aides and social workers, grocery store employees, fast food workers, and package handlers.

The cost-benefit calculation of whether to keep showing up at work becomes an easier one if you can’t afford to stay home. In Philadelphia, as in many big cities, low-wage workers are more likely to be people of color, making those communities disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is a racial breakdown available for roughly one-quarter of the city’s more than 2,000 positive COVID-19 cases. Among that subset, 46% of the cases are Black non-Hispanic, 37% are white non-Hispanic, 3% are Asian, and 10% are Hispanic.

Black Philadelphians are overrepresented here: They make up about 44% of the city’s population as a whole. Hispanics are slightly underrepresented: About 15% of Philadelphia is Hispanic, according to the most recent census data.

But those numbers should be taken with a grain of salt, said Sharrelle Barber, an assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health. Without citywide capacity for testing asymptomatic people and doing contact tracing, most of Philadelphia’s testing is done in a health care setting.

“What you have to think about is who has access to health care that can go in to get tested,” said Barber.

Access to health care

In 2016 in Philadelphia, a city Department of Public Health study showed that the rate of Hispanics without health insurance was more than double that of non-Hispanic whites. In Philly, more than half of the areas with low access to primary care have high concentrations of Black and Hispanic residents, that same report showed.

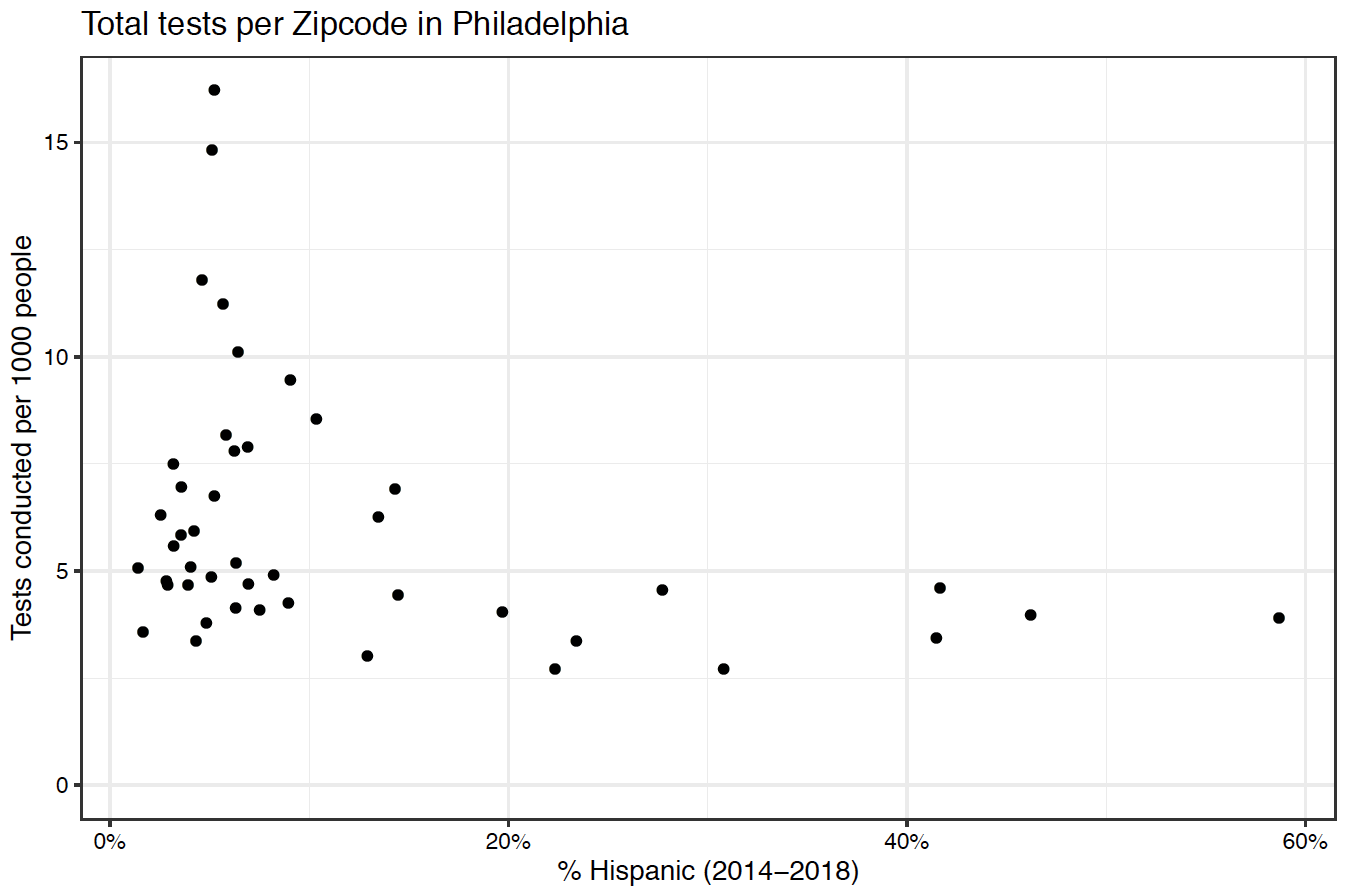

Usama Bilal, a social epidemiologist at Drexel, demonstrated in a graph that the areas with the highest concentrations of Hispanic residents saw the fewest tests.

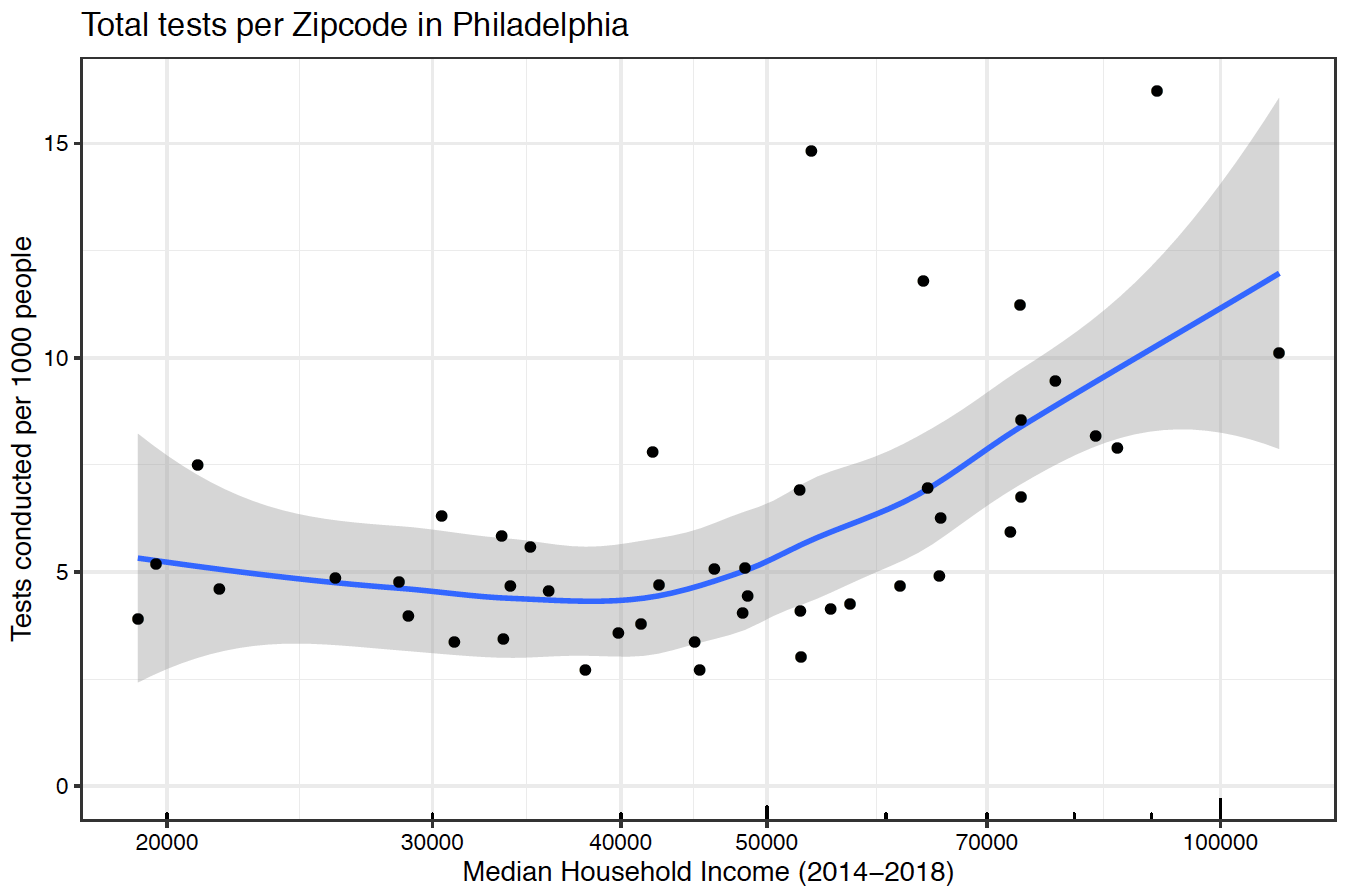

While the large, drive-through test site run by the city’s Department of Public Health does not require health insurance, lines to get tested are often long and require a car. Bilal’s analysis shows that, in general, wealthier zip codes had much higher rates of testing than those in lower-income areas — in some of the city’s wealthiest zip codes, people were tested at three times the rate of its poorest.

In the event that people of color do become hospitalized, Barber worries about how racial bias in medicine could affect the care people receive. Inequities could be made even more pointed by the shortage of life-saving medical equipment, like ventilators, that hospitals are facing across the country.

“We may see racialized patterns of survival based on the choices that doctors … have to make about who lives and who dies,” said Barber.

In a March 25 essay in The Atlantic, “How the Pandemic Will End,” science writer Ed Yong says, “There are now only two groups of Americans. Group A includes everyone involved in the medical response, whether that’s treating patients, running tests, or manufacturing supplies. Group B includes everyone else, and their job is to buy Group A more time.”

But that’s a dramatic oversimplification. Doctors and those producing chemical reagents are not the only ones keeping America functioning.

For the last three days, Ernest Garrett’s phone has been ringing off the hook. As the business manager for the union representing Philadelphia Water Department workers, Garrett has been fielding calls about the end of time-and-a-half pay for essential city workers, after two weeks during which the Kenney administration maintained that policy.

“You tell ’em for two weeks, `You’re essential, we’re gonna take care of you, give you an increase in your daily rate,’” said Garrett. “Two weeks later, we’re still under the same stressful conditions, you tell ’em `Well, you know what, we can’t financially keep going like this.’”

Garrett said the Water Department was doing its best to protect workers — often, they were deployed to their vehicles first thing in the morning to avoid overcrowding in administrative buildings. Still, workers were going into houses to turn on shut off water lines, repair leaks, and unclog sewers, sometimes without protective gear.

He said he’d heard from supervisors buying scarves for their teams and carrying around homemade bleach solutions to sterilize the insides of vehicles between uses. The extra pay might have made the risk worth it, but now the calculus is different.

”How can you say … we still want you to do this job, we just don’t have the money to pay you?” he asked.

Nearly 60% of the Water Department’s 2,169 workers are people of color, according to city data.

The proportion is even greater at the city’s jails, where 85% of workers are people of color. There, the time-and-a-half order also expired. But at least 500 of the orderlies, doctors, and nurses that have been showing up at work each day are technically contracted by the city, and didn’t get the pay increase at all. As of Thursday, Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said, there are 20 confirmed cases of coronavirus within the city’s prison population.

Workers in the city’s homeless shelters face a similar challenge.

“In all honesty, it can be very, very challenging to social distance at work,” said Jimenez. “Do I feel unsafe? Absolutely. I think for myself to say that I feel that way would be a little naive. That’s a fact, right?”

Less able to socially distance

Not only are essential workers more likely to be exposed to the virus on the job, they are also less likely to be able to take the recommended social distancing measures to prevent getting infected, or to be able to self-isolate if they do get the virus.

Philadelphia’s high density, especially in higher-poverty neighborhoods, can make it harder for residents in those areas to keep their distance. Barber gave the example of an essential worker with a higher risk of exposure coming home each day to an overcrowded apartment.

“Not only is the individual themselves at risk, but now their families are at risk, and perhaps folks in their communities,” she said. “We can see how, as this pandemic unfolds over time, it not only puts individuals within marginalized racial groups at risk, but whole communities.”

Ultimately, Barber said, the brunt of the pandemic is going to weigh the heaviest on the communities that have long suffered from structural inequity. She stressed that mapping the concentrations of infections allows authorities to direct resources to areas with the most cases.

“These communities have already been distressed and disinvested,” she said. “They’re gonna need more help.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)