Death of bullied Utah girl draws anger over suicides, racism

“No parent should have to bury their 10-year old,” said the girl's mother. “I’m still in shock."

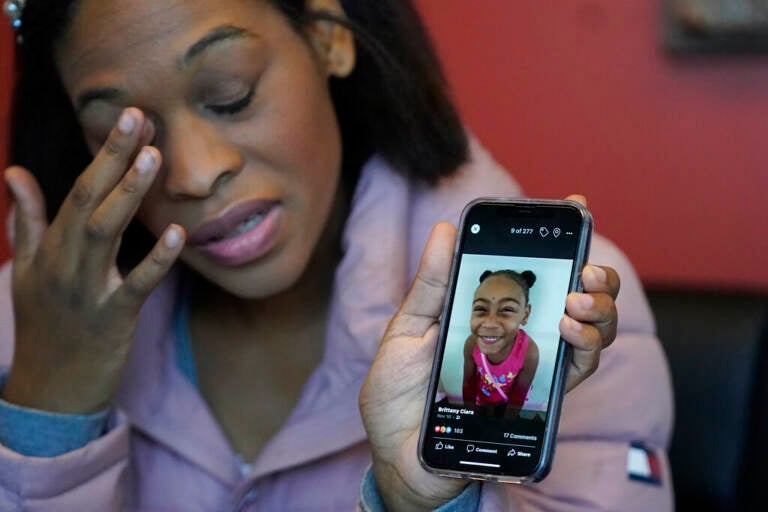

Brittany Tichenor-Cox, holds a photo of her daughter, Isabella "Izzy" Tichenor, during an interview Monday, Nov. 29, 2021, in Draper, Utah. Tichenor-Cox said her 10-year-old daughter died by suicide after she was harassed for being Black and autistic at school. She is speaking out about the school not doing enough to stop the bullying. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

When her 10-year-old daughter tried spraying air freshener on herself before school one morning, Brittany Tichenor-Cox suspected something was wrong with the sweet little girl whose beaming smile had gone dormant after she started the fifth grade.

She coaxed out of Isabella “Izzy” Tichenor that a boy in her class told her she stank after their teacher instructed the class that they needed to shower. It was the latest in a series of bullying episodes that targeted Izzy, who was autistic and the only Black student in class. Other incidents included harassment about her skin color, eyebrows and a beauty mark on her forehead, her mother said.

Tichenor-Cox informed the teacher, the school and the district about the bullying. She said nothing was done to improve the situation. Then on Nov. 6, at their home near Salt Lake City, Izzy died by suicide.

Her shocking death triggered an outpouring of anger about youth suicides, racism in the classroom and the treatment of children with autism — issues that have been highlighted by the nation’s racial reckoning and a renewed emphasis on student mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Utah, the suicide also intensified questions about the Davis School District, which was recently reprimanded by the Justice Department for failing to address widespread racial discrimination.

The district, where Black and Asian American students account for roughly 1% of the approximately 73,000 students, initially defended its handling of the bullying allegations but later launched an outside investigation that is ongoing.

“When I was crying out for help for somebody to do something, nobody even showed up for her,” Tichenor-Cox said this week in an interview with The Associated Press. ”It just hurts to know that my baby was bullied all day throughout school — from the time I dropped her off to the time I picked her up.”

Being autistic made it difficult for Izzy to find words to express what she was feeling, but her mother sensed her daughter was internalizing the messages from school. She asked her mother to get rid of the beauty mark and shave her unibrow. Her mother told her those features made her different and beautiful. She told her mother her teacher didn’t like her and wouldn’t say hi or help with schoolwork.

Izzy’s mother, 31, blames the teacher for allowing the bullying to happen. Prior to this year, she said, Izzy and two of her other children liked the school.

Tichenor-Cox has also called out deep-rooted racism in the predominantly white state of Utah, where she said the N-word that kids called her when she was a child in the 1990s is still hurled at her children three decades later.

But she doesn’t want fury to be her only message. She vows to make Izzy’s life matter by speaking out about bullying, racism and the importance of understanding autism so that no other parent has to suffer like she is.

As she looked at a picture on her cellphone of Izzy smiling with fresh braids in her hair last May, Tichenor-Cox teared up as she realized that was her last birthday with her dear daughter who dreamed of being a professional dancer.

“No parent should have to bury their 10-year old,” she said. “I’m still in shock. … This pushes me to get this out there like this. Mommy is pushing to make sure that this don’t happen to nobody else.”

Davis School District spokesman Christopher Williams did not answer questions about the investigation, the employment status of Izzy’s teacher or about any direct accusations. He instead referred back to a Nov. 12 statement in which the district pledged to do an outside investigation to review its “handling of critical issues, such as bullying, to provide a safe and welcoming environment for all.”

The Justice Department investigation uncovered hundreds of documented uses of the N-word and other racial epithets over the last five years in the district. The probe also found physical assaults, derogatory racial comments and harsher discipline for students of color.

Black students throughout the district told investigators about people referring to them as monkeys or apes and saying that their skin was dirty or looked like feces. Students also made monkey noises at their Black peers, repeatedly referenced slavery and lynching and told Black students to “go pick cotton” and “you are my slave,” according to the department’s findings.

The district has agreed to take several steps as part of a settlement agreement, including establishing a new department to handle complaints, offering more training and collecting data.

Tichenor-Cox told the AP she doesn’t trust the district’s investigation and said the district has zero credibility. Instead, her attorney, Tyler Ayres, hired a private investigator to do their own probe as Tichenor-Cox considers possible legal action.

She and Ayres also said the Justice Department is looking into what happened with Izzy. The agency would not say if it’s investigating what happened to Izzy at the school but said in a statement Wednesday that it is saddened by her death and aware of reports she was harassed because of her race and “disability.” The department said it is committed to ensuring the school district follows through on the plan established in the settlement agreement.

Youth suicides in Utah have leveled off in recent years after an alarming spike from 2011 to 2015, but the rate remains sharply higher than the national average. The state’s 2020 per capita rate was 8.85 suicides among 10- to 17-year-olds per 100,000, compared with 2.3 suicides per 100,000 nationally in 2019, the latest year with data available.

Tributes to Izzy are scattered on social media under #standforizzy. The Utah Jazz basketball team honored her at a recent game, and players Donovan Mitchell and Joe Ingles, who has an autistic son, both expressed dismay over what happened, calling it “disgusting.” Other parents from the school district have sent letters to the school board calling out the district’s “dismissive actions.”

Tichenor-Cox and her husband, Charles Cox, have five other children to focus on, so they’re doing all they can to handle the grief while trying to remember the sparkle Izzy brought to their lives for a decade.

“I want her to be remembered of how kind she was, how beautiful she was, how brilliant she was and intelligent she was,” Tichenor-Cox said. “Because if I keep thinking of what happened, it’s just going to put me back, and I’m trying to be strong for her.”

___

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. The hotline is staffed 24/7 by trained counselors who can offer free, confidential support. Spanish speakers can call 1-888-628-9454. People who are deaf or hard of hearing can call 1-800-799-4889. Help can also be accessed through the Crisis Text Line by texting “HOME” to 741-741.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.