City Council passes resolution condemning secrecy of supervised injection plans

City Council passed the measure, 15-2, as groups both in support of and against Safehouse showed up in force bearing signs representing their positions.

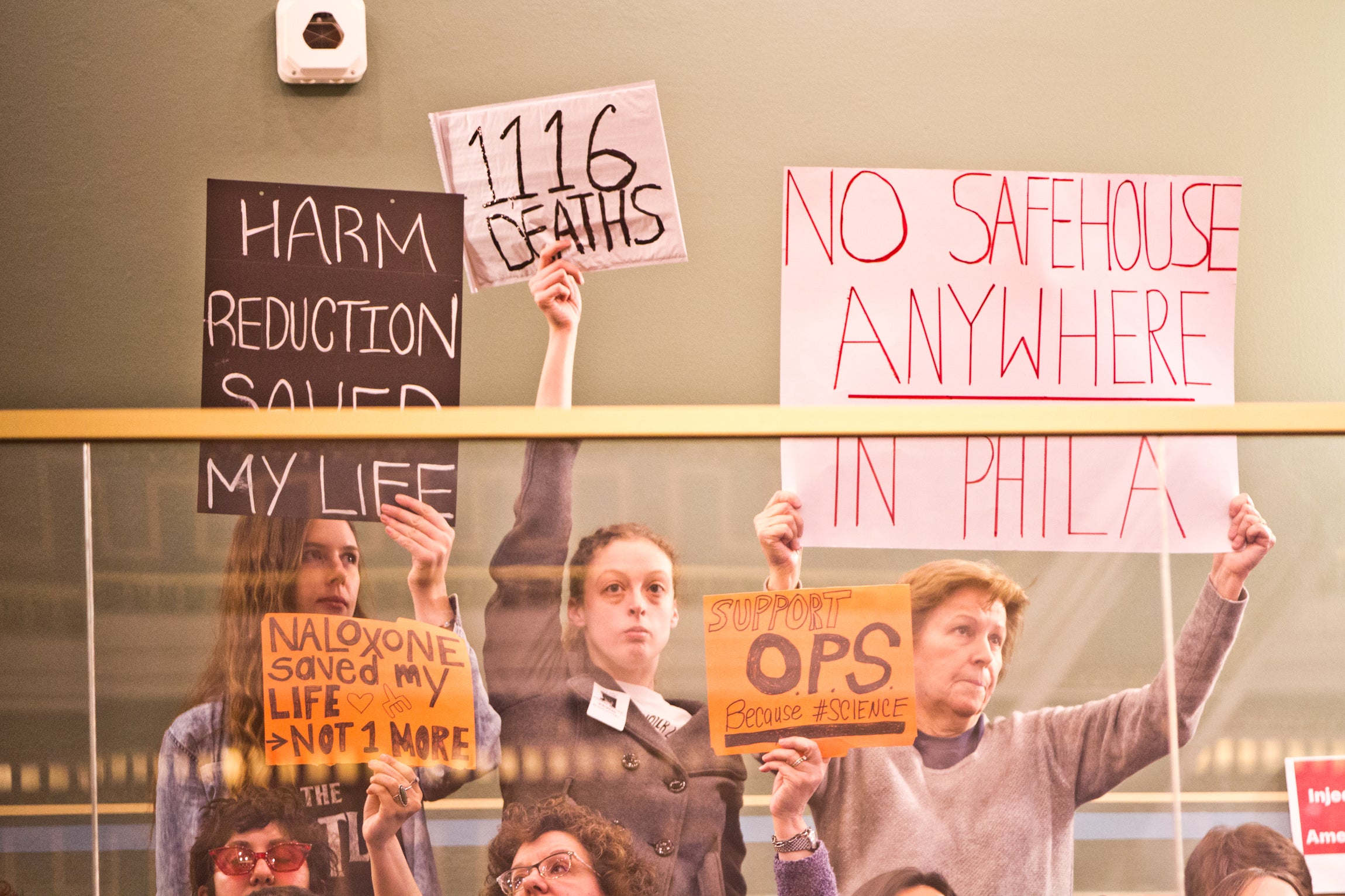

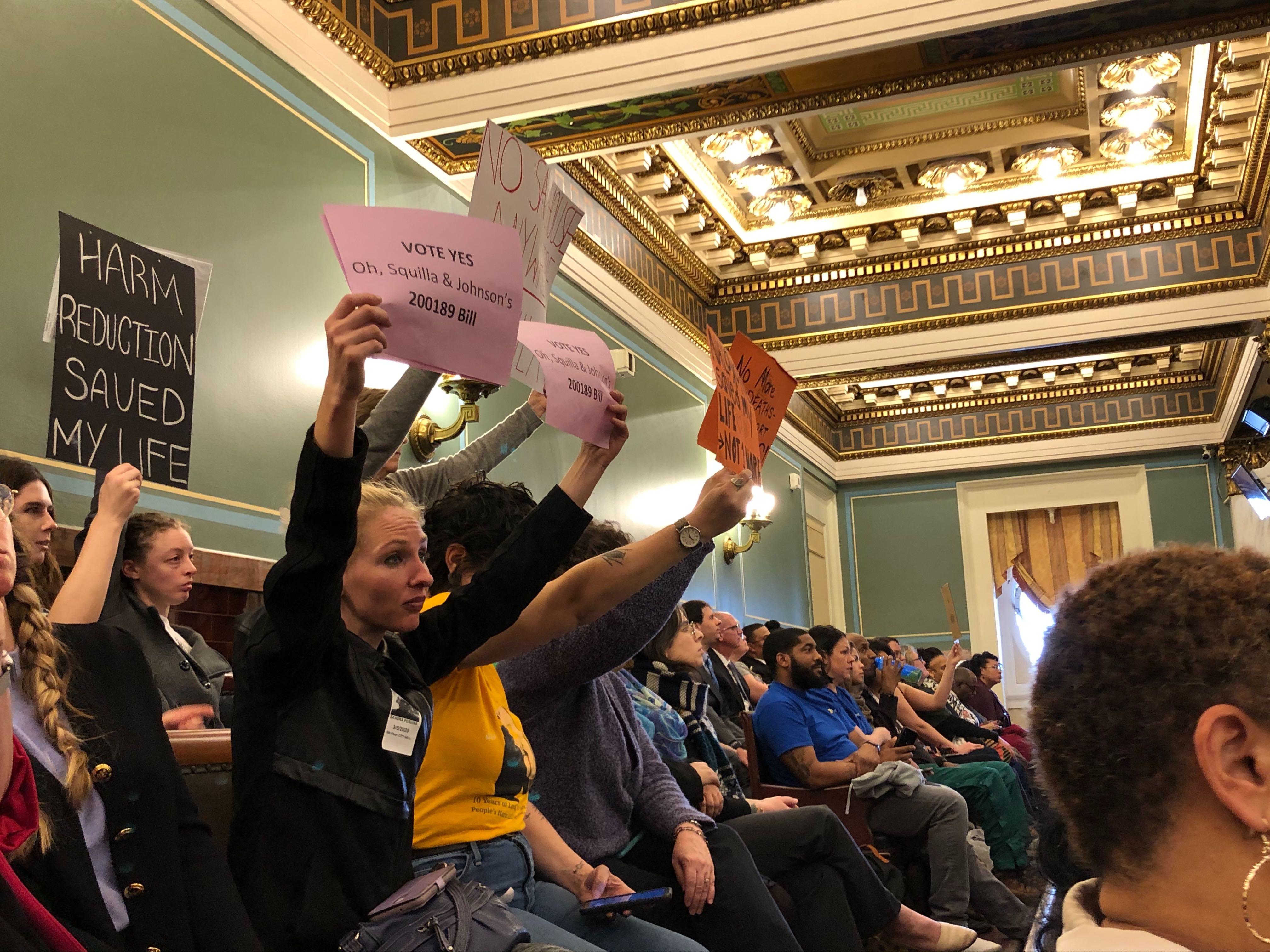

People in support of and opposed to Philadelphia’s Safehouse injection site protested in City Council on March 5, 2020. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

City Council passed a resolution Thursday urging Mayor Jim Kenney to back off plans to open a supervised injection site.

The bill, introduced by Councilmember David Oh, condemns the lack of transparency on the part of the city and the nonprofit Safehouse in attempting to open what would have been the nation’s first supervised injection site. The resolution passed, 15-2, with Councilmembers Helen Gym and Kendra Brooks voting against it.

Groups both in support of and against the supervised injection site showed up in force at the council’s chambers, bearing signs representing their positions.

“It’s like a sci-fi movie to me, it’s really bizarre” said Maureen Fratantoni, who has lived in South Philadelphia her whole life, a few blocks from where the proposed site would have gone. “To take illegal drugs into a facility and to actually be escorted in to do the drugs, it’s like nothing i’ve ever heard of before here.”

Fratantoni added she felt completely taken off guard by the announcement that the site would go in Constitution Health Plaza on South Broad Street, where she was born when it was St. Agnes Hospital.

“I have doctors in there,” she said. “Who’s going to take care of us? Who’s going to make sure that we’re safe?”

Even Safehouse supporters acknowledged that the nonprofit did a poor job of involving the public.

“You’re talking about bringing something into a community that’s controversial and it’s going to generate a lot of emotion, and community engagement is just really important,” said Bill Kinkle, who is in recovery and has supported Safehouse in the past. Even if community meetings didn’t change anybody’s mind, Kinkle said, they’d be worth it, if nothing else as an opportunity to educate those for whom the concept of supervised injection may be new, and to clear up misconceptions.

In his support of Oh’s resolution, Councilmember Mark Squilla, who has long opposed supervised injection sites, cautioned against relying too heavily on evidence showing that such sites reduce overdose deaths, which he said is not entirely conclusive.

Though the illicit nature of supervised injection sites and a resistance to use randomized controlled studies to examine them makes them uniquely hard to research, Squilla suggested without evidence that increased overdose deaths in British Columbia between 2006 and 2018 may have been caused by opening supervised injection sites. Researchers and the Canadian government widely acknowledge that the deadly opioid fentanyl contaminating the drug supply is the primary culprit for the spike in overdose deaths.

In another effort to undermine research backing the sites, Squilla also highlighted a meta-analysis, published by the University of South Wales, which found that the methodologies of some studies on supervised injection sites to be flawed. That meta-analysis has since been retracted on the basis of flawed methodology.

Squilla said that instead of supervised injection, which he views as enabling, the city should focus on giving better access to treatment for substance abuse disorders. He listed the city’s smoking ban at inpatient rehab centers as an unnecessary barrier to treatment.

Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson, in whose district Safehouse would have gone before its plans for the South Philly site were thwarted last week, spoke in favor of the resolution. In the past, he has cited the government-sponsored war on drugs that plagued much of the Black community during the crack epidemic as a reason for opposing supervised injection sites. But his colleague Kendra Brooks said that’s exactly why she supports them.

“Nothing will change that pain or the necessity of our government to right the massive wrongs made during that era,” Brooks said. “The trauma still rings in my body — as do the stories of countless Philadelphians who die each week from overdoses.”

Brooks said she refused to think of a supervised injection site as a moral failure, while accepting as normal the deaths of more than 1,000 Philadelphians each year.

Brooks was joined by Helen Gym in her opposition to the resolution. Gym agreed that a better public process is necessary, and recounted her visits to three different overdose prevention sites around the world, which she said were all successful, in part, because they were the product of community conversations and public stewardship.

But she said it’s also important that any bill acknowledge the role of supervised injection as one element in the battle against addiction.

“They are not the solution, they are not the beginning, and they are not the end, but they are part of a continuum of care that recognizes that you cannot recover, you cannot detox, and you cannot survive if you are dead.”

The passage of the resolution Thursday was largely symbolic, though Oh introduced an accompanying bill that will be heard Monday. If passed, it would amend the city’s health code to classify supervised injection sites as “nuisance health establishments,” a category created in 2014 meant to crackdown on “pill mill” medical facilities that were giving out opioid prescriptions too freely. Oh’s bill would require anyone wanting to open a supervised injection site to publicize the intent to do so six months in advance, and to get 90% approval from the surrounding community.

The mayor promised to take a larger role in encouraging community conversation, as his administration did when a location was being discussed for Kensington. But he didn’t back down on his overall intention to support a site opening.

“I want to be very clear that I refuse to look another parent in the face and tell them I didn’t do everything I could to try and keep their child alive long enough to survive their disease,” he said.

Max Wander said they are living proof that it’s worth keeping people alive long enough to get them into treatment. In recovery for 2 ½ years, Wander held a sign during Thursday’s council session that read, “Naloxone saved my life.”

Wander, who uses they/them pronouns, and their mother took the train to Philadelphia from Lancaster to show their support for supervised injection sites. Wander said while using, they overdosed three times. Each time, someone revived them with naloxone.

“If I was using alone, who knows, I probably wouldn’t still be here,” Wander said. “I’m someone who didn’t die, and now I’m a stable, working member of my community. I’m just the same as people who were using on the street. I was using on the street three years ago.”

Wander said if, God forbid, they ever did end up using again, they would be glad for a supervised injection site.

“I don’t want to die,” they said. “I don’t think drug users do.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.