City approves plan to build luxury housing in Conrail’s backyard

The ruling is the latest example of the board allowing real estate interests to skirt existing land use regulations, despite community opposition.

A rendering of an interior courtyard planned for 2035 Lehigh Ave. (courtesy of KJO Architecture)

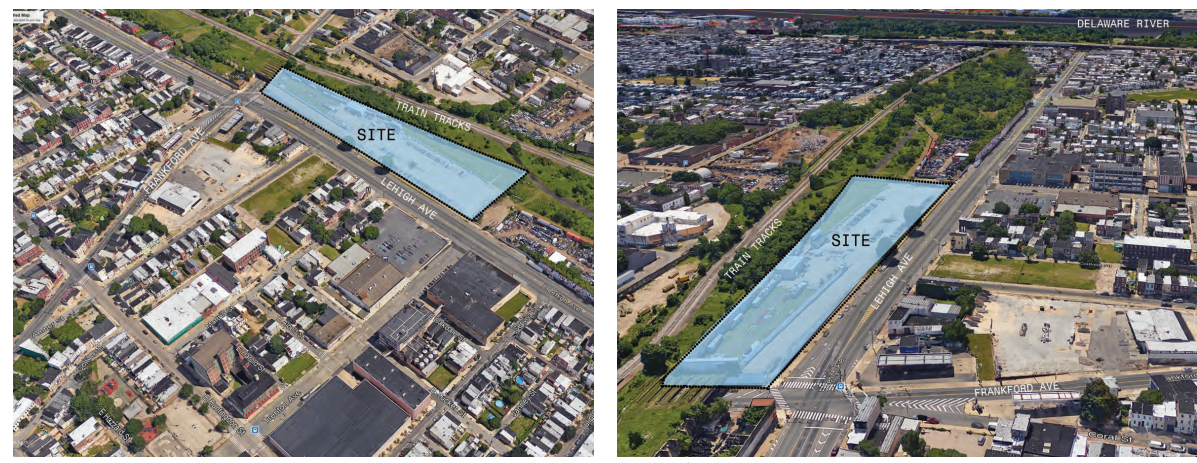

Hard against the clanging Conrail train tracks in an industrial section of Kensington, the four-acre vacant lot at the corner of Lehigh and Frankford avenues doesn’t look like the most obvious place for $369,000 single-family homes. The block-long tract of land sits within shouting distance of encampments set up by heroin users and the stretch of Lehigh it borders ranks as one of the city’s most dangerous corridors, with a high rate of fatalities and severe injuries per mile.

But after a three-to-one Zoning Board of Adjustment vote on Wednesday in support of building housing on the barren 2035 Lehigh Avenue site, 155 units are cleared for construction. The affirmative ZBA vote flew in the face of objections from the City Planning Commission and neighborhood groups who argued that the Riverwards Group development doesn’t accord with community planning efforts or recently minted zoning, which specifically does not allow residential construction.

“We can’t be comfortable with residential development this close to an active freight rail line,” said David Fecteau, the city planner in charge of the area, during a presentation to the Planning Commission on Tuesday. “We are caught flat-footed by this proposal because Philadelphia doesn’t have any standards for building residential development adjacent to a freight rail line. But we do have serious safety concerns here.”

The commission supported Fecteau’s objection and voted against the variance that the ZBA approved one day later. The advisory board’s chief objection rested on safety concerns stoked by the site’s location and the city’s recent history of train derailments. Adding to fears is the fact that tankers bearing chemicals and other potentially harmful substances run along the Conrail tracks. The project also garnered two harsh reviews from the city’s advisory Civic Design Review Board with architects and other professionals on the board arguing that the design could be improved and that more should be done to improve safety conditions for pedestrians.

The ruling is the latest example of the board allowing real estate interests to skirt existing land use regulations, despite community opposition.

A prominent neighborhood organization, New Kensington Community Development Corporation (NKCDC), testified against the project at the Planning Commission and the ZBA and a gathering of community groups in December voted narrowly against it.

“We have a particular issue with this project because it goes against five years of community planning,” said Andrew Goodman, the community engagement director with NKCDC, during public testimony at the Planning Commission. “Zoning and land use regulations are designed to set a vision for the highest and best use for properties for years to come, not to be constantly edited based on who is to putting a bid on a property.”

The developer packed the ZBA hearing with supporters, some of whom, upon questioning, proved to be employees of the real estate agent brokering the deal. But other community members organically came out to support the project. Andrew Ortega, who lives around the corner from the site, spoke passionately in favor of the development. (Although he is on the board of the East Kensington Neighbors Association, he only testified on behalf of himself.)

“All my neighbors were excited, we were all ecstatic,” said Ortega, who said he had a petition with signatures from 24 near neighbors in support of the site. “When we look at that end of the street, the world just ends. It’s just an empty space, with the railroad blocking everything north of there.”

The developer needed variances for landscaping requirements around parking and for electric car charging stations. But these were not contested by NKCDC or other neighborhood groups.

They object to the variance required to put housing on the site — currently zoned for a mix of industrial and commercial uses specifically meant to encourage commercial development on former industrial sites. The zoning category is designed to be used as a buffer between industrial areas, like the Conrail tracks, and largely residential ones.

The lot got remapped only last summer, with input from NKCDC and other community groups, who imagined it redeveloped for commercial purposes in a variety of neighborhood plans over the past few years. The groups hope to see business development on the site and believe there’s the demand to support it; of the 16 commercial corridor blocks under NKCDC’s purview there are only four vacant storefronts, Goodman said.

But Thomas Chapman, a lawyer from Blank Rome representing RiverWards Group, argued that the neighborhood is hungry for residential development.

“We view this as for folks who would like to move into Fishtown, or a neighborhood like it, but can’t afford the prices in Fishtown,” said Chapman, who noted that the prices range from $199,000 to $369,000. The developer has sold out other high-end residential projects in the area including a gated townhouse development in Port Richmond and a few luxury townhouse developments in Fishtown.

Chapman noted on Tuesday that the RiverWards Group already responded to some of the earlier critiques of the Lehigh Avenue project with tweaks to the plan. The developer reduced the number of car parking spots and created more spaces for bicycles. The company also reoriented the residential development on Lehigh Avenue to face to the street in response to feedback from the Civic Design Review Board. Earlier plans showed the houses running perpendicular to the busy arterial road. The developer answered a call for more commercial uses on the site by replacing six single-family houses with mixed-use buildings that will include spaces for three to six businesses to open shop.

From the developer’s perspective, the current zoning, the planners’ objections, and the community’s hopes for the area don’t match what the market will actually bear. Chapman told the Planning Commission that the mixed-use buildings are the only part of the project that hasn’t yet attracted financing.

The news that the developer is still raising money to complete the project raised additional questions from planning commissioners who feared that if the RiverWards Group got its variances they would only end up building the single-family homes and doing away with plans for the mixed-use buildings.

The site faces a variety of other complications as well. The developer’s representatives told the Planning Commission that its soil is contaminated and 1.4 million cubic feet of chemical-laced dirt will have to be removed to allow for construction. The freight trains that travel by the site carrying chemicals and sometimes crude oil to the Tioga Marine Terminal will continue to raise questions for the developer. A 2014 ProPublica investigation found “at least 65 cases over the last two years, tank cars bound for or arriving in Philadelphia were found to have loose, leaking or missing safety components.” As a hedge against possible hazards associated with proximity to the Conrail tracks, RiverWards Group plans to build an eight-foot high reinforced concrete wall between the route and its homes. Asked if the wall would be “blast resistant,” representatives of RiverWards Group said they were not yet sure.

Despite all these challenges, the developers remain bullish on the site — and the strength of the Fishtown-Kensington market.

“This is a difficult site and when it was first proposed I was surprised,” said Chapman. “I personally believe the developers are brave in taking on this project but, nevertheless, I think this could encourage other positive impacts in the area.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.