Center City housing construction meeting demand, but challenges loom

Center City District’s new report takes the pulse of the housing market in Greater Center City and finds scant evidence of a rental housing bubble forming in the near future.

But they argue that the relatively sunny outlook over the next few years is no cause for complacency, as future headwinds from demographics and regional job growth trends threaten to dampen the pace of new construction.

The takeaway, as anyone familiar with CCD President Paul Levy’s long-standing advocacy priorities might guess, is that Philadelphia needs pro-growth tax reform and more school funding to reduce our competitive disadvantages with the suburbs and other metros.

A few of the key takeaways:

Fueled by Apartments, Rentals

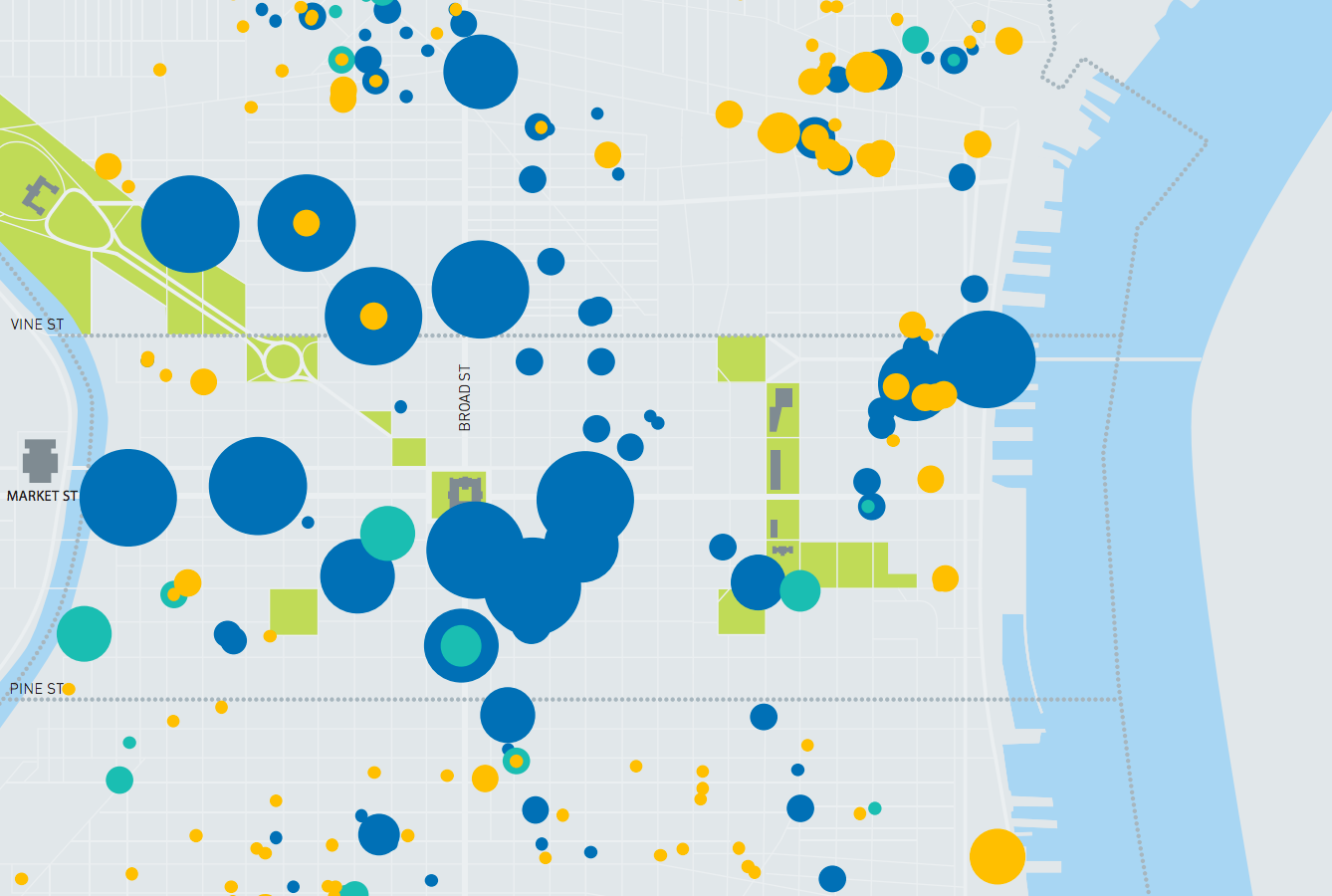

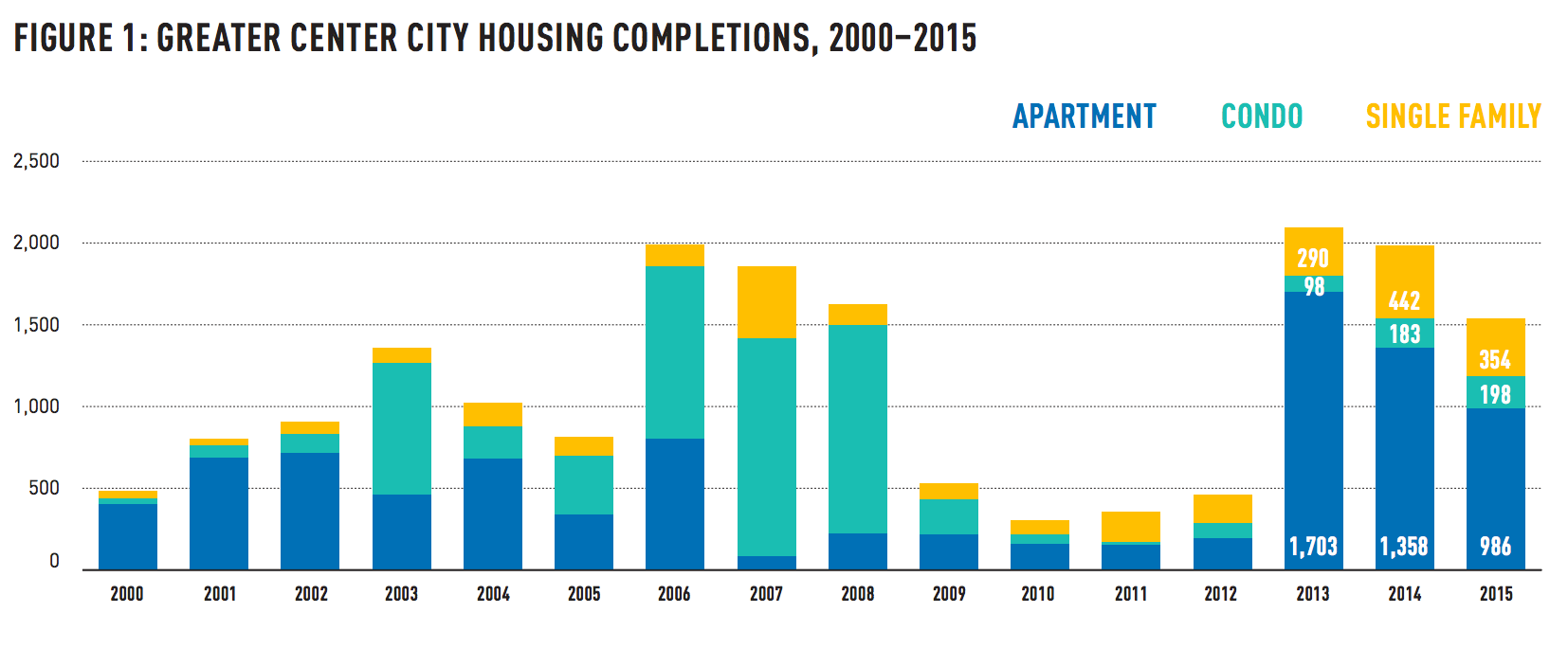

In total, 1,500 housing units were brought to market in 2015, of which 64% were rentals. Sixty-one percent of those rentals were located in the core Center City area. For-sale houses made up the other 36%, and 98% of those were built outside the core in the extended Greater Center City area, which CCD defines as Girard to Tasker between the rivers.

Apartment construction has dominated for the last three years, with a total of 4,047 apartment units brought to market in Greater Center City during that time. This has powered a nice V-shaped housing recovery, coming off several below-average construction years between 2009-2012. Center City gained population during those years, but developers didn’t build very much housing, so some catch-up growth was to be expected.

The pace of construction slowed a bit in 2015, with 1,538 units completed—22% fewer than the 1,983 units completed in 2014, and 26% fewer than the 2,091 completed in 2013.

But lest anyone mistake this for a gentle downward slope, CCD counts 5,833 units (78% of which are rentals) now under construction, with “2,063 units scheduled for completion in 2016, 1,708 in 2017, 391 in 2018, 407 in 2019.”

“This does not factor in more than 8,000 proposed apartment units that have been announced in press releases, newspaper stories and on-line blogs, but have not yet broken ground,” the authors note.

Too much housing construction? (Not yet.)

As we’ve reported, the market has had no trouble thus far absorbing all the new apartments, and the report bears this out.

But CCD points to challenges that could put a damper on future housing construction if policy remains on autopilot: The generation following behind the current cohort of young adult housing consumers is roughly 11% smaller; job and wage growth remain weak, and the city’s share of regional jobs is still stuck around 25%; city public schools are chronically underfunded by the state legislature.

The report warns that better job offers in the suburbs and other cities, or the call of suburban schools that spend about 50% more per-student on average, will exert strong exit pressure on the highly-mobile group powering most of the recent housing construction, and an alternative strategy is needed. The authors devote only one paragraph in the conclusion to what that strategy should be specifically, suggesting a combination of the Levy-Sweeney tax reform plan and winning a fairer school funding formula from the state.

Ideal housing vacancy rate and affordability

Projecting forward the average residential growth rate since 2010, CCD predicts an increase of 3,897 new households for Greater Center City over the period between 2016 and 2018. That works out to 1,299 households per year, during which time 1,944 new units are scheduled for completion—an overage of about 650 units.

That 650-unit per year gap is invoked as part of the case for urgency in dealing with Philly’s competitiveness problems. The report strongly suggests something must be done to address it, either by attracting or retaining an additional 650 households a year to keep the housing market from loosening.

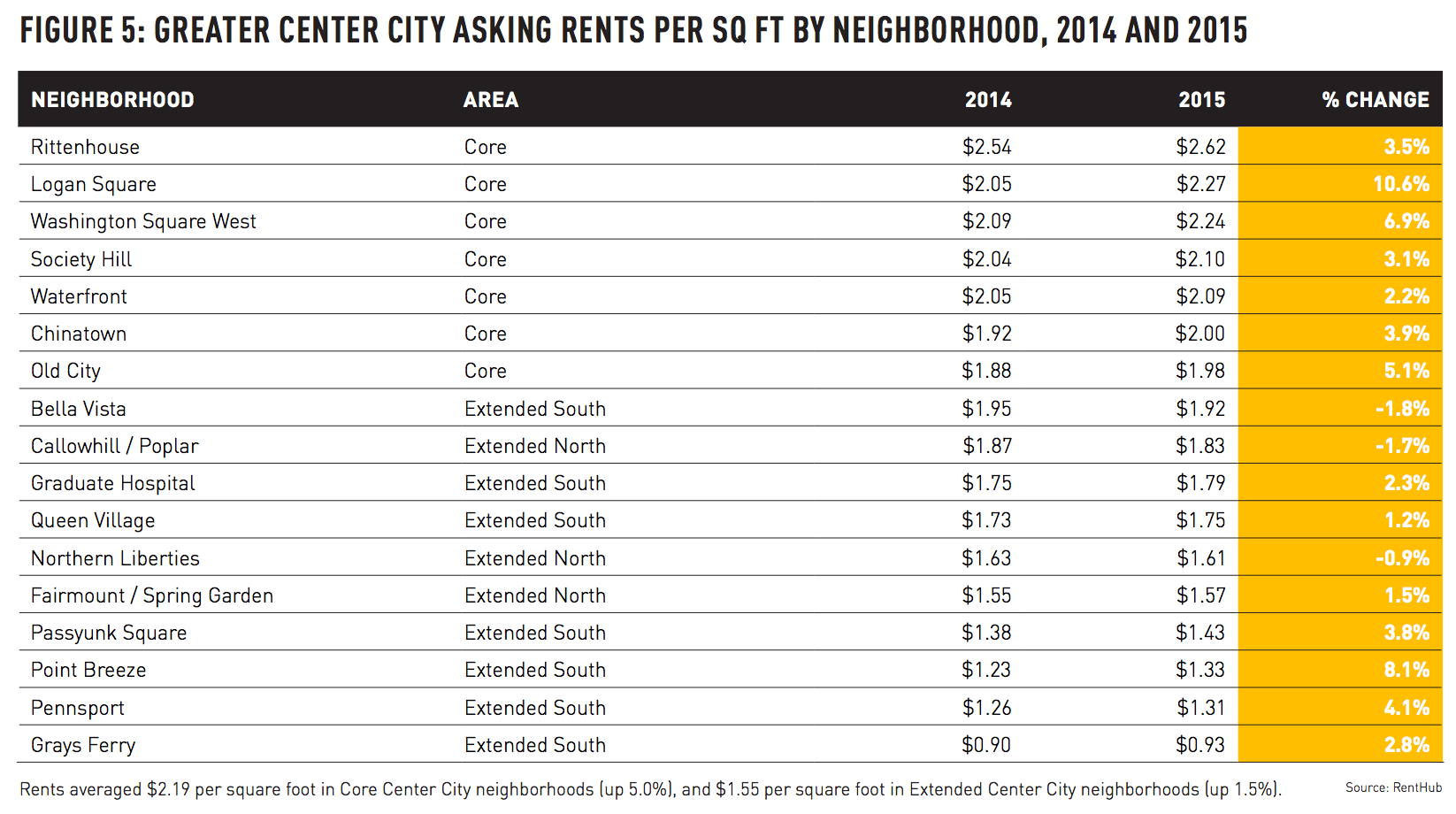

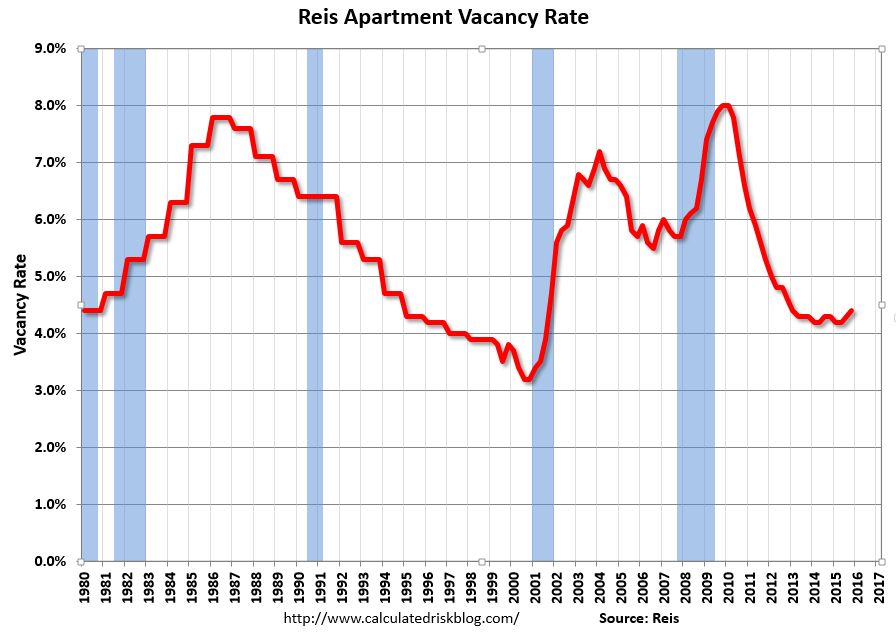

But this assumes that the current housing vacancy rate is ideal, which is a highly debatable premise. After the apartment vacancy rate dipped to an almost unthinkably low 1.6% over the summer, vacancies in the apartment market (which dominates new housing construction in Center City) are now up to a still extremely-low rate of 2.8%.

To put that in context, the Reis index, which tracks national apartment vacancy rates across large U.S. markets, shows the national apartment vacancy rate stands at 4.4%. The period between 2013 and 2015 featured the second-lowest vacancies recorded since Reis began tracking in 1980, with rates hitting bottom at 4.2% in 2013. Even the lowest-recorded quarter for vacancies in 2000 didn’t reach as low as 3%. Ordinarily, vacancy rates have tended to hover in the 5-7% range.

So a 2.8% apartment vacancy rate represents a fairly severe rental housing shortage, and the report’s authors are silent as to why, in a market this tight, that rate would be considered a desirable baseline. Rental markets normally function with a substantially larger cushion.

As the report’s authors state in a footnote, if Philly goes wanting for those 650 new households each year, the “alternative is 650 existing units go vacant or a portion of the new units take longer to be absorbed than their developers or lenders prefer. The fact that there are about 90,000 units of occupied housing in Center City puts this number in perspective.” Another possibility is that landlords will lower their asking prices, luring in more people.

For context, an extra 650 vacant units would mean a 0.7% increase in the vacancy rate each year. If developers continued to add the same number of units each year, without changing their investment strategies in response to a loosening market, it would take four years before the rental market achieved a 5.6% vacancy rate, closer in line with the historical average.

At a time when rent growth and housing affordability are hot political topics, and very expensive strategies abound for constructing new sub-market rate housing, wouldn’t maintaining a modest oversupply of housing units be a good thing for those who aren’t landlords or developers?

To get a flavor of what would happen, read some of the recent real estate business news out of Seattle or Washington, DC, where there’s some evidence that an “oversupply” of housing is slowing rent growth in high-construction areas, and unleashing horrors like “free rent” in the more competitive marketplace.

“Meanwhile, across all markets, more landlords are offering tenants sweeter incentives, such as free rent,” the Puget Sound Business Journal reported in December of last year. “The average value of incentives is $15 a month this quarter, which is nearly double what it was last quarter, when 16 percent of landlords were offering incentives. Now 20 percent are.”

Philadelphia so far appears to be doing an exemplary job of providing sufficient housing supply to keep up with demand, unlike some of our peer cities who are under-building in the face of ballooning rents. The party might not last forever, but insofar as low-cost housing is also one of Philly’s major competitive advantages, prematurely taking away the punch bowl by aiming for low vacancy rates seems mistaken.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.