Camden is inching toward ‘swimmable’ waterways, but Trump administration cuts threaten progress

Unlike modern infrastructure, which utilizes separate piping systems, Camden’s older sewer systems send stormwater and sewage through the same underground pipes.

Listen 1:03

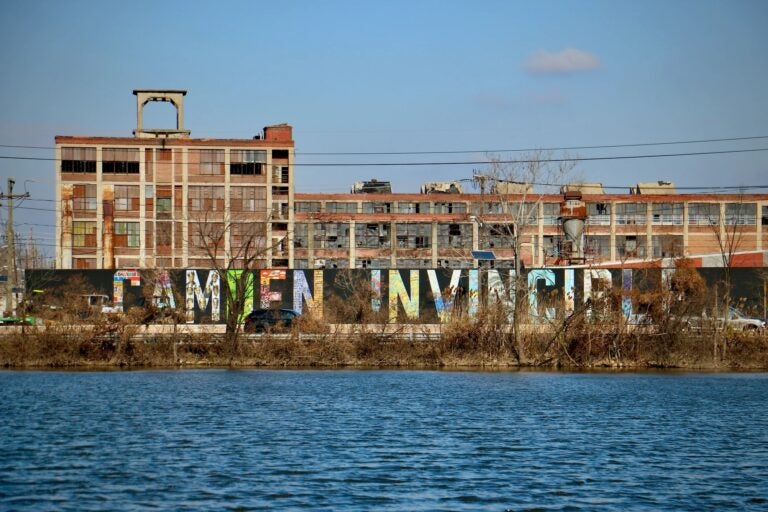

File - With the backdrop of an abandoned factory, the ''Camden Invincible'' mural faces Admiral Wilson Boulevard and the Cooper River, seen in January 2022. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Swimmable waterways have long been the goal of the federal Clean Water Act, passed in 1972.

But more than 50 years after its passage, older industrial cities such as Camden and Philadelphia struggle to reach that level of cleanliness because of outdated sewer systems.

Unlike modern infrastructure, which utilizes separate piping systems, older sewer systems send stormwater and sewage through the same underground pipes.

During heavy rain, this combined sewer/stormwater system can overflow, spilling raw sewage into the region’s rivers and streams. The overflow can also mean flooding in nearby communities.

Camden’s main waterways, the Cooper and the Delaware rivers, often contain fecal bacteria levels that make it unsafe for humans to swim, fish or even kayak.

But the Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority, or CCMUA, is taking steps officials hope will change the trajectory of local water quality. Last month, the state of New Jersey awarded the sewer and wastewater authority for investing in infrastructure that is diverting millions of combined sewer discharges from the state’s waterways.

“As people are becoming re-engaged with our waterways, especially the Cooper River in Camden County, we know it’s not meeting water quality standards,” said Scott Schreiber, executive director of the CCMUA. “The CCMUA is fully committed to restoring that water quality to these rivers and streams, so people can go kayak and people can do things like recreate in and around water with confidence that they won’t get sick.”

The CCMUA, a regional facility founded 1972, provides wastewater treatment for about 500,000 residents in Camden County’s 36 municipalities.

In 2021, the authority completed construction on a $20.5 million multi-project initiative that expanded its stormwater capacity from 150 to 185 million gallons a day. That means each year, the authority is able to accept 300 million gallons of additional sewage for treatment.

“It’s 300 million gallons a year that didn’t go to the Delaware, or Newton Creek, or Cooper River, and polluted it with viruses and bacteria and nutrients,” said Oleg Zonis, the CCMUA’s director of engineering. “It’s 300 million gallons that didn’t end up on the streets of Camden and Gloucester, or any other areas that potentially could be affected by flooding.”

Even if the water quality reaches a point that allows swimming, there are parts of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers that will never be safe for swimmers due to currents and tides.

Prior to the federal Clean Water Act, the Delaware River between Trenton and Philadelphia supported virtually no life at all. More than 50 years ago, regulations requiring facilities to treat wastewater before discharging it changed what was once a “stinky, ugly mess” into a place where hundreds of thousands visit its urban shorelines each year.

Treatment plants along the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers provide clean drinking water to about 15 million people. However, urban parts of the Delaware River and its tributaries are still too polluted to swim in.

Swimming and kayaking are permitted in much of the Upper Delaware River, which is regulated by the Delaware River Basin Commission. However, for a 27-mile stretch along Camden and Philadelphia, the DRBC restricts residents to boating and fishing.

Schreiber said even if a waterway isn’t capable of supporting swimming and fishing, the goal remains the same.

“The water quality goals should be the same, which is to have the cleanest water possible,” he said. “But that is going to take serious time and serious investment in order to get there.”

Trump administration cuts threaten progress on clean water

The authority is also working on additional projects that will help the county meet federal regulations requiring municipalities to reduce 85% of stormwater and sewage overflow.

A $26 million project will separate Pennsauken’s combined sewer into two flows: sanitary and storm.

Pennsauken currently sends its combined sewer flow through the city of Camden, which makes its way to CCMUA’s treatment facility.

In the future, stormwater from both Pennsauken and Camden will discharge into the Delaware River, while a separate sewage flow will be directed to CCMUA’s treatment plant.

A longer-term project, costing $14 million, involves developing green infrastructure on Harrison Avenue in Camden that aims to reduce flooding and runoff pollution, along with separating stormwater and sanitary pipes.

The authority is also partnering with Camden and Gloucester to help the municipalities reduce combined sewage overflow, which could cost about $200 million.

The CCMUA relies on the Environmental Protection Agency’s state revolving fund, which offers low-interest financing for water quality projects. However, the Trump administration has proposed to cut the U.S. agency’s spending by 65%, which some say could reduce state revolving fund dollars.

Schreiber said that could mean projects necessary to meet environmental regulations would be put on hold. Other projects that help the environment but aren’t required by law would likely be upended, as municipalities would be forced to prioritize, he said.

“It’s hard to imagine that that budget cut wouldn’t impact the state revolving fund seed money,” Schreiber said. “If folks want us, the way we want, to continue to create clean water and improve water quality, we absolutely must have that seed funding from Washington, D.C., otherwise for every project that we do now, we would probably only able to do about a half a project in the future because of the cost of financing.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.