Black Phish fans tell the good, the bad, and the ugly in new podcast

Blackberry Jams will dissect the jam band experience for Black fans, in the context of Black Liberation.

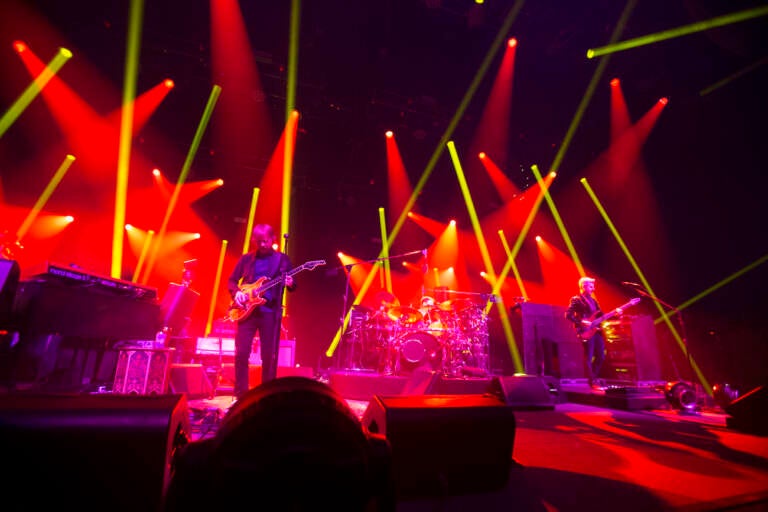

Page McConnell, from left, Trey Anastasio, Jon Fishman and Mike Gordon of the band Phish perform during an exclusive concert for SiriusXM and Pandora listeners at The Met on Tuesday, Dec. 3, 2019, in Philadelphia. (Photo by Owen Sweeney/Invision/AP)

A West Philly native is the co-creator and co-host of a new podcast, Blackberry Jams, about a very specific demographic: Black people who love the Vermont-based jam band Phish.

Lenny Duncan admits it is a small group of people.

“Here’s the funny thing about life,” said Duncan in a Zoom interview from his home in Portland, Oregon. “I thought that there were so few Black Phish fans, but almost immediately when we announced the show we found a Facebook group full of almost a hundred of them that know a couple hundred more. They’re all communicating with each other.”

“More importantly, Black people know the experience of trying to fit into white scenes and just be free like everyone else. There are moments of joy,” he said. “Then there are moments of macro- and micro-aggressions. This happens all the time. And the Phish thing is not exempt. Systemic racism is systemic racism.”

Duncan has been a fan of Phish and the greater jam-band scene since the mid-1990s, when he was living on the streets of Philadelphia as a homeless teenager. A Volkswagen bus of Deadheads offered him a ride and a ticket to see the Jerry Garcia Band.

“Those kids saved me. I mean, I was on 13th Street selling my body,” he said. “I didn’t get the music, they were just kind people. Someone gave me a ticket and I walked into a Jerry Garcia Band show in 1993. I suddenly got it.”

Duncan went on to become an ordained minister, the founder of the religious community Jubilee Collective, and the author of several books including, “Dear Church: A Love Letter from a Black Preacher to the Whitest Denomination in the U.S,” based on his time in the Evangelical Lutheran Church.

Duncan said he grew up primarily with hip hop and “good soul.” He had known about the Grateful Dead and Phish, which put out its first major-label record in 1990, but hardly gave them a second thought.

“The thing about good live music, you don’t get it until you show up,” he said. “Even me, as a Phish fan, I can’t listen to a lot of shows after the show. I’m like, ‘Wow, they really kind of blew that part.’ But in the moment, when you have 60,000 people dancing with you and no one’s bothering you — there are very rare places you can do that in America as a Black person.”

Blackberry Jams, presented by Ben and Jerry’s ice cream, may find an audience outside its specific base of Black fans of jam music, by promising to unpack those rare moments of Black joy which are set in an environment where racial tension still exists. Duncan says he is often assumed to be a bouncer at shows instead of a fan, or a drug dealer, or a ticket scalper.

“But that same thing would happen to me in front of City Hall in Philadelphia. ‘What are you doing? What are you up to? Let me see your I.D.’” he said “At least Phish concerts kids are a little bit nicer: ‘Is this your first show?’”

Duncan and his co-host Leslie Mac, both diehard fans, will release one episode of Blackberry Jams a week, for 10 weeks, delving into the history, culture, and Black experience of jam band concerts, in particular Phish. They have released a toll-free number, 888-PHAN-JAM (888-742-6526), where people can leave voice messages describing their best, and worst experiences at shows.

“I’m so excited to talk about the good, the great, and the ugly with my friend Lenny, who I’ve spent many hours dissecting everything from our favorite ‘Tweezer Reprise’ to which show venues are the most racist,” said Mac, a Black community organizer, and activist, in a statement. “Telling these stories will offer a peek into how music helps me cope with the difficulties of the world and my hopes for how this scene can change to meet the current moment.”

Even though there are relatively few Black people there, Duncan sees the Phish fan scene as a landscape for Black Liberation. He points to the early days of Grateful Dead shows, emerging from the 1960s counterculture which attempted to upset the prevailing power structures of the time. The band was known to play benefit concerts for the Oakland chapter of the Black Panthers.

Duncan sees himself as having come of age during the “last bastion of ‘60s esoterica and psychedelia,” but with lessons learned through the stories of Mumia Abu Jamal, Ramona Africa of MOVE, the Black Panthers, and the Nation of Islam. He says it’s a “power analysis given to me the only way you get it being Black in America, and that’s through violence.”

Duncan believes Phish shows are able to rally the intentions of the 1960s counterculture and shape them into a future for Black Liberation in America.

“That is the republic,” he said. “In its essence, what the republic is is moments like this where you and I can lower our disposition to one another just enough that we can imagine that something divine might be on the other side.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.