Black Doctors Consortium calls on Philly hospitals to offer rapid community testing

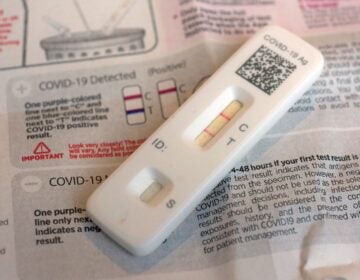

Hospitals can turn COVID-19 tests results around in hours. The Black Doctors Consortium says that should be offered to communities most affected by the virus.

Flanked by fellow doctors, Dr. Ala Stanford, founder of the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, speaks to reporters in the parking lot of the West Philadelphia Seventh-day Adventist Church. (Christopher Norris/WHYY)

Are you on the front lines of the coronavirus? Help us report on the pandemic.

At a City Council hearing on Tuesday, Dr. Ala Stanford, head of the Black Doctors’ Consortium, blasted Philadelphia’s hospital systems for not reaching out more proactively to the communities they know are most vulnerable to the coronavirus.

“Don’t just stay in the hospital,” she challenged them. “Leave your edifice, go out to the communities that need you most.”

Stanford is a pediatric surgeon by trade, but her grassroots group won a city bid to conduct testing among Philly’s Black residents.

She noted the $579 million in federal funding that Philadelphia area hospitals received through the CARES act.

“The resources are there,” she said.

In Philadelphia, overall death rates for Black residents are 50% higher than those for white residents. Latinx people over age 75 have the highest death rates per 10,000 residents in the city.

In response to these inequities, which are consistent with national trends, the city’s Public Health Department released what it called an “interim plan” Monday to address the racial and ethnic disparities amplified by the virus. City Council heard testimony from Stanford and others who spoke on the need to examine those disparities.

Stanford noted that, while the people visiting her testing sites often have to wait 10 to 14 days for results to come back due to log jams at national labs, hospitals are equipped to test in-house and get results back within hours. She suggested that local health systems set up a rotating schedule where each opens their doors to the community for rapid testing one day a week, including weekends, and extending beyond the standard weekday, 9 to 5 hours. She also pushed to eliminate any requirement for identification, citing it as a barrier to testing.

Health Commissioner Tom Farley agreed that hospitals could do more, noting that if people don’t isolate during the time it takes to get their results back, which for many is unrealistic, getting tested becomes pointless.

“If they could each take some, at least some of the people would get a test result in a meaningful time period,” said Farley of the hospitals.

Einstein recently started such a program, offering free testing, no prescription necessary, available Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. and Saturdays from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Councilmember Derek Green, who co-chaired the City Council hearing with Councilmember Cindy Bass, said the committee plans to send a letter to other hospitals, asking them to do the same.

Philadelphia is currently conducting about 3,000 tests a day at 56 sites throughout the city. The goal, according to Farley, is 5,000 tests at 75 sites. In its plan for interim racial and ethnic equity, the city commits to broadening testing efforts and outreach specifically in Black and Latinx communities.

Stanford and Dr. Alberto Esquenazi of Einstein both emphasized that while underlying health conditions like obesity, diabetes and smoking rates are often cited as the reason the coronavirus hit Black communities harder, the Black and Latinx patients they see struggle more due to limited access to health care.

Stanford pointed to examples of people who she’s tested in church parking lots and street corners in her capacity as head of the Black Doctors Consortium: A Black grocery store worker whose white boss said she wasn’t sick enough to get tested, or an elderly funeral home director in West Philly who wanted to get tested, but was turned away because he didn’t have a prescription.

“That has nothing to do with his hypertension,” Stanford said. “That has everything to do with your implicit bias.”

The City Council hearing also included testimony from those who spoke on behalf of people with disabilities and the elderly, who are both disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of the pandemic. More than half of Philadelphia’s COVID-19 deaths have been long-term care residents, and Philadelphia has the third largest proportion of residents with disabilities in the country, at about one-sixth of the population.

Koert Wehberg, executive director of the Mayor’s Commission on People with Disabilities, noted many of those residents were in congregate care facilities, such as nursing homes, when the pandemic hit, and are also more likely to have underlying conditions.

People with cognitive disabilities are often sensitive to changes in routine, making the impact of stay-at-home orders and remote learning incredibly disruptive. Remote work is often more difficult for those with disabilities, leading to disproportionate furloughs and layoffs.

Wehberg also said people with disabilities had trouble accessing food at the start of the economic shutdown.

“If you have an underlying health condition or disability, you might be unable or afraid to leave your home to get food,” he said.

In its plan, the city outlines how it will support those who are unable to quarantine at home, for example, due to crowded living conditions or because they are experiencing homelessness. The city has issued a request-for-proposal from community organizations that can offer food, medications, masks and other supplies, as well as temporary housing.

The Public Health Department plans to train its COVID-19 response team on the racial equity plan, and incorporate its metrics into the public coronavirus data dashboard to measure progress.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)