‘Birth of photography’ on display at the Barnes Foundation

In 1840, photography was both the runt of the fine art world and its greatest threat.

Listen 2:25-

Desire Charnay’s photographs of the Grand Palace of Mitla in Mexico, 1860. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Peter Henry Emerson’s Gathering Water Lilies, 1885. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Collector Michael Mattis explains the secret behind the perfectly exposed skiers of Gustave Le Gray’s landscape photography. (Kimberly Paynter?WHYY)

-

Collector Judy Hochberg with Gustave Le Gray and Auguste Mestral’s photograph of the West Portal of the church of Saint-Ours Loches, a blue-toned salt print, 1851. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

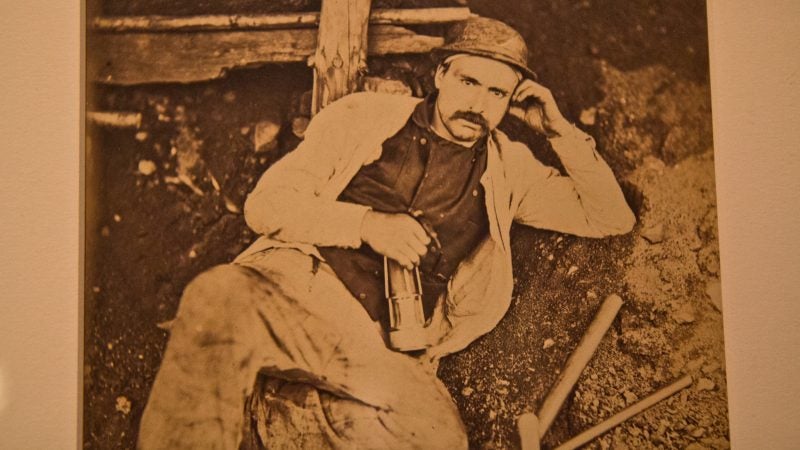

A French portrait from an unknown photographer from 1860. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Thomas Collins is the Neubauer Family Executive Director and President at the Barnes. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Original photographic prints from 1840 to 1880 illustrate the birth and early life of photography in a show opening this weekend at the Barnes Foundation.

At the time, inventors and artists were trying to figure out photography, technically and artistically. As the new medium strove to gain a foothold in the world of fine art, it threatened to upend it.

“From Today, Painting Is Dead,” gets its title from something supposedly said by the French painter Paul Delaroche in 1840 as he viewed a photograph for the first time.

What exactly he was looking at and whether he actually spoke those words are up for debate. Even if he did make that pronouncement, it’s hard to assess the tone: Did photography herald an artistic apocalypse or its disruptive rebirth?

“Whether that was a positive or negative statement, it betrays the anxieties a talented painter would have felt upon recognizing the potentials of photography,” said Thom Collins, the head of the Barnes Foundation and the curator of this exhibition.

The reigning art academies of London and Paris, which set the bar for almost all of Western art for hundreds of years, followed a rigid set of rules that determined the quality of a painting. The “hierarchy of genres” put paintings of historic and biblical scenes at the top, followed by portraiture of aristocracy, then pictures of underclass people, then landscape paintings. Bringing up the rear was still life.

Early photography, whose exposure times could be measured in minutes or even hours for a single picture, was only really good for still-life pictures ﹘ maybe landscapes if the wind were calm. The rules of art did not suit photography.

“Photographers inherited a visual vocabulary from painting. To look at the way in which photographers navigated that inheritance ﹘ this show has proved so rich,” said Collins. “We live, now, in a world in which visual culture is defined by photography and photo-related forms like cinema. This exhibition attempts to gauge the way in which early photographers turned things around.”

There are nearly 250 photographs in “Painting is Dead,” ranging from early botanical experiments in 1840 to popular forms of commercial studio portraiture from 1880. (The show’s timeline ends before Kodak’s mass-produced “point and shoot” cameras entered the marketplace.) Along the way there was travel photography of ancient temples in India and China, death photos of loved ones (including the executed corpse of Maximilian I of Mexico), and even a little bit of stereoscopic pornography, circa 1860.

Capturing ‘the quality of magic’

They all come from the vast private collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg of Scarsdale, New York, who have amassed thousands of vintage, original photographic prints. They range from Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1970s works to 1840 when William Henry Fox Talbot, a wealthy gentleman scientist in England who invented photosensitive paper, took pictures of plants.

“He was kind of a polymath,” said Hochberg of Talbot. “He was interested in lots of things, including botany. He wanted to draw things he saw and was frustrated he couldn’t do it well. Wouldn’t it be nice to use the sun to create a likeness, instead of having to do it by hand?”

Talbot developed a technique of exposing a negative image on paper, then shining a bright light through the negative onto a positive print. Unlike the daguerreotypes of the time (and later tintypes), which were positive exposures directly onto treated metal plates, Talbot’s negative technique could make multiple prints from the same exposure.

Another pioneer was Hippolyte Bayard, a French photographer who developed a technique of positive exposures onto paper prints. The amount of light required to make a picture in his technique was so great, he had to work outside in sunlight.

Whatever happened inside Bayard’s camera during the exposure, that was it. There was no secondary darkroom process to make adjustments.

“Sometimes the exposures were so long, he had no idea if it would result in a picture at all,” said Collins. “There’s a quality of magic in those pictures.”

Collins has tapped into the photographic collection of Hochman and Mattis before, in 2016 for the exhibition “Live and Life Will Give You Pictures.” That show focused on early 20th century French art photography; this show takes a deeper dive into the mid-19th century holdings of the Mattis/Hochberg collection.

Hochberg, the self-described “mistress of the database,” sheepishly admitted she isn’t sure exactly how many photographs they own.

“We love having this show at the Barnes, because that’s what he did,” she said, referring to Albert Barnes. “He was a crazy private collector who had a great eye and put together this extraordinary collection that was very focused ﹘ and at the same time broad.”

By the way, photography did not kill painting. The famous, core exhibition of post-impressionist and modernist masterworks at the Barnes is a case in point. The camera’s ability to mechanically record what people and places look like freed painters to make more expressive canvases.

“Painting had to find another reason to exist, rather than simply representing reality,” said Hochberg. “Perhaps that’s why impressionism would come down the pike in a couple decades.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.