As gunfire continues killing Philly teens, city musters new approaches to violence

So far this year, nearly 30 minors have been fatally shot in Philadelphia. Last year, 22 teens were shot and killed.

Listen 6:49

Police investigate a drive-by shooting in Germantown on Oct. 3, 2018. Five young men aged 19 to 23 were shot. One died. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

More than one out of every 10 gunshot victims in Philadelphia is a teenager. Each year, that translates into about 150 teens wounded by gunfire. And on average, about two dozen of them die from those injuries.

City records obtained from the Philadelphia Police Department show that the grim toll of gun violence on teens has budged up and down incrementally, but the numbers have stayed stubbornly in the same range for years.

Teenagers in Philadelphia face a greater risk of being shot than Boston’s youth. Minors are twice as likely to be shot in Philadelphia than in Baltimore, records show. Of the city statistics reviewed by WHYY, only Chicago — where roughly a quarter of all gunshot victims each year are 19 or younger — was more dangerous for teens.

Philadelphia spends tens of millions of dollars a year on anti-violence efforts, yet statistics from the police department’s research and analysis unit show no program or initiative has successfully shielded teens from a gun violence rate that has remained virtually unchanged since 2015.

“It does keep me awake at night,” Police Commissioner Richard Ross said at police headquarters recently. “Most of these victims have not had a chance to live their lives. They’re younger than you and I. It’s got to stop.”

Top officials in City Hall are also alarmed at how frequently 13- to 19-year-olds experience the physical and emotional trauma of firearms before they graduate from high school.

“We’ve all had somebody we care about be the victim of gun violence,” said Vanessa Garrett Harley, the city’s deputy managing director for criminal justice and public safety. “The urgency is certainly not lost on us.”

Garrett Harley, who is helping lead a city audit of the millions expended each year on anti-violence initiatives, will release a report in the coming weeks. The internal probe follows Mayor Jim Kenney’s declaration that gun violence constitutes a public health crisis — and an ultimatum of 100 days for his cabinet to find new approaches.

When it comes to combating violence, Harley acknowledged, “To be frank, I don’t think the city actually had a comprehensive plan.”

Theron Pride, the top city official overseeing violence prevention, said part of the city’s focus going forward will be supporting people he calls “credible messengers” to interrupt violence in the communities.

“Because engaging the population that we’re most concerned about, there’s a trust issue. ‘I don’t know you. You haven’t walked in my shoes. How can I look for you to help me?’ ” Pride explained. “We need to have people really from the community helping guide the community.”

Tymeer King, a 17-year-old who attends Overbrook High School in West Philadelphia, would be a strong candidate for this line of work.

Barely old enough to drive, he already has experienced more loss than most adults twice his age. His dad, his uncle, and a close family friend, who went by the name Haag, all died from gunshots.

“I think about Haag, my dad, my uncle, I think about everybody I lost every day,” said King, choking back tears. “I have dreams about them almost like three nights of the week. Since then I just haven’t been able to get close to another male.”

King shared that moment in a room full of other teens who know the toll of gun violence firsthand. It’s a program run by the group Frontline Dads, which mentors young boys who have grown up under tough conditions. Sometimes, like King, they have participated in the city’s chaotic gun violence themselves, but have since put down their firearms and now encourage their friends to do the same.

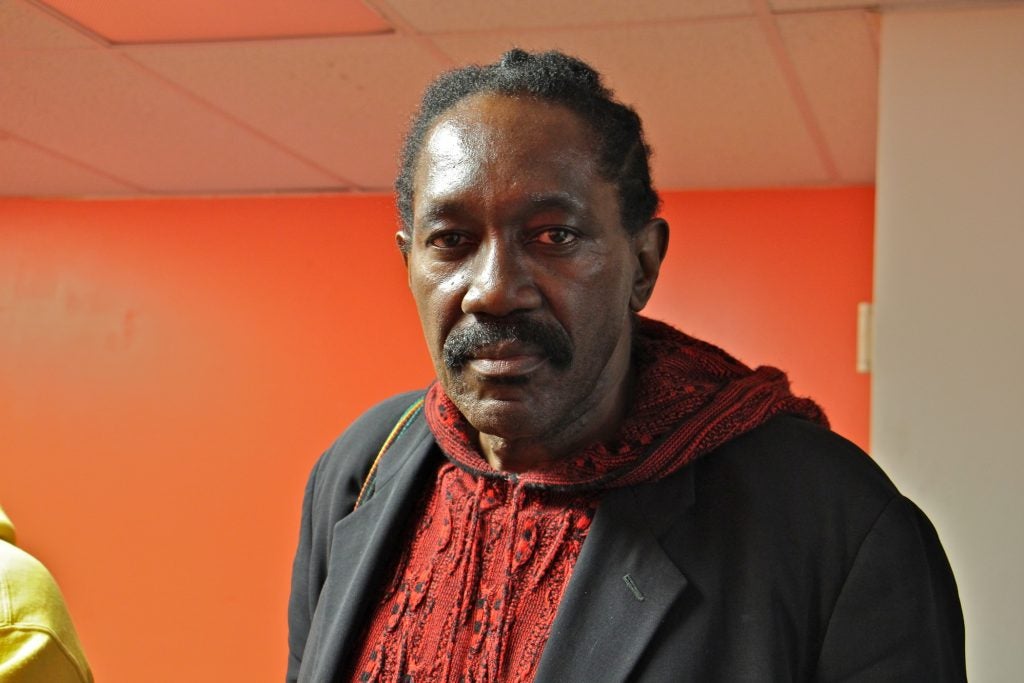

Reuben Jones spent 15 years in prison for a robbery case in the 1980s and now leads Frontline Dads. He tries to teach young men small lessons to process their trauma and provide them with a roadmap on how to diffuse an escalating situation.

“Healing is a part of overcoming all those feelings that you feel like you weren’t able to grieve and cry and release,” Jones tells King, as the group of young people listen on with rapt attention. “And when people do that, it builds up in here, and it comes out some ways like a pipe — you close off one end, that water is going to come out somewhere when the pressure builds up enough.”

This is exactly why Jones holds these meetings: to provide a release valve for King and other teens who may have lost fathers, have trouble expressing their feelings, and are part of a world that encourages violence over the civility of mediation.

The inability to do this has fatal consequences.

So far this year, nearly 30 minors have been fatally shot in Philadelphia. Last year around this time, 22 teenagers had been shot and killed. Although that represents just a tenth of all fatal shootings in the city, officials are distressed that for too many of the city’s youngest residents, gunfire continues to take away scores of lives. Since 2015, records show, the number of teens killed by bullets has not fluctuated much.

King said he watches feuds igniting over trifling matters — taunting someone on Instagram; walking around in a rival neighborhood; listening to a rapper who has connections to an enemy at school; even just looking at someone.

Here is a scenario that is not uncommon: King said he’ll be walking along the school hallway and see someone staring him down. He’ll talk to someone else for a couple minutes, try to ignore the person gawking at him, but the gaze isn’t broken.

“I look back over, he’s still staring,” he tells the room. “What would ya’ll say?”

“Hi,” Jones and others say in unison.

“I’m not gonna be like, ‘Hi, how you doing, I’m Tymeer,’ ” he said, as other teens chuckle at this suggestion. “I’m gonna say, ‘What’s up?’ ” he says in a daring, come-at-me tone with both hands out.

If that “what’s up” is taken as a threat, it can cause problems down the road, said Jones, who is accustomed to helping young men negotiate these fraught social interactions.

“In their environment, making eye contact can cost you you’re life,” Jones said. “So you become averse to eye contact. Whenever you have eye contact it becomes a challenge: ‘What you looking at? What’s your problem?’ ”

Joseph Douglas, who runs the mentoring group Black Men Assisting Black Boys Alliance, nods his head in agreement.

“A lot of violence is based on machismo,” Douglas said, noting that Philadelphia’s status as the most impoverished big city in America is a fact that intensifies feelings of desperation among young men.

“So you got a poor person, somebody with low self-esteem, a lot of times all you have is your manhood,” he said.

Getting together to unpack masculinity is not something most teen boys would jump to sign up for. Yet King and a dozen others ended up in the room as a part of a second-chance program: a court-ordered diversionary program that will allow them to avoid jail and a criminal record.

It’s the type of community-based engagement that the city is exploring as part of its new approach to tackling citywide violence.

Already, King said, the discussions have prompted him to have conversations with friends who’ve thought about turning to gun violence to settle a score. Here is what he’s said to one friend:

“What’s your mom gonna do without you? You sitting there in prison for life because you kill someone,” he said. “Even if you get away with it, you’re thinking about that every day. It mentally scars you because you took somebody’s life away.”

This summer, the city launched a program where crisis responders work overnight to monitor neighborhood tensions. When they hear about something brewing, a team of three will head out and try to defuse the conflict. Top city officials are considering expanding that effort.

In addition, Harley with the city said the Kenney administration will soon be handing out micro-grants to fund small, one-off efforts to prevent gun violence.

“Something as simple as, ‘We’re hearing there’s going to be some violence tonight, so we’re gonna hold a basketball game to keep everybody off the streets,’ ” she said.

Back in West Philadelphia, Jondhi Harrell, who spent 25 years in prison before becoming an activist and runs the Center for Returning Citizens, was talking to the dozen teens in the room.

“It’s not that serious,” Harrell said. “Many of the insults that you perceive to be so life-threatening, next week you won’t even remember it. So it’s developing the critical thinking skills to see past situations and to make critical decisions that impact life and death. Nobody is teaching that on the streets.”

Harrell said he would like to see more city resources pledged to teaching teens conflict resolution, especially when those who have formerly served time in prison — people like himself and Jones — are the ones directing it.

But one major obstacle?

“Nobody wants to put money in the hands of formerly incarcerated people,” Harrell said.

The city, for its part, denies that suggestion.

Top City Hall officials say the goal is not necessarily to increase funding to anti-violence programs. Instead, officials would rather support initiatives that are most likely to work, particularly when the solution includes a way of disrupting brewing tensions, as well as assisting those still reeling from the tumult of violence recover and move on.

“The impact is far greater than the lives lost,” Pride said. “The ones who experienced and are exposed to that daily, the ongoing assault, that violence and those shots.

“Yes, the problem is difficult and, yes it’s been very hard, but people have been encouraged to know that we’re focusing on it in a new way now.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.