As Pennsylvania health systems rapidly adopt AI, lawmakers take steps to regulate the technology

Health systems and insurance companies are using artificial intelligence to analyze CT scans and MRIs, update electronic health records and review coverage decisions.

Listen 5:08

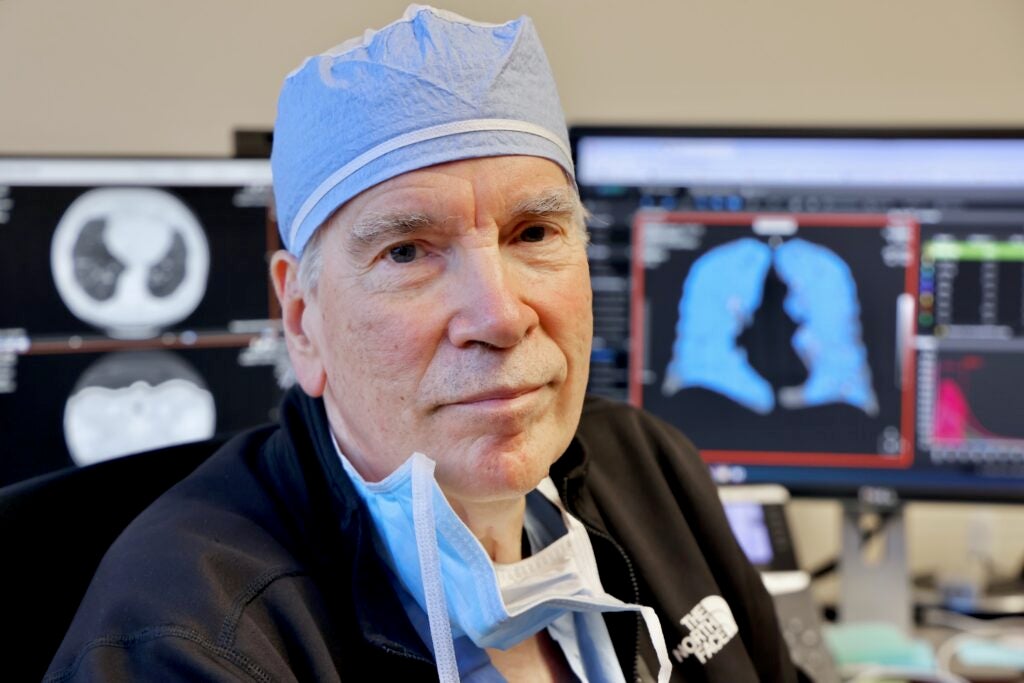

Dr. Gerard Criner, director of Temple Lung Center (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

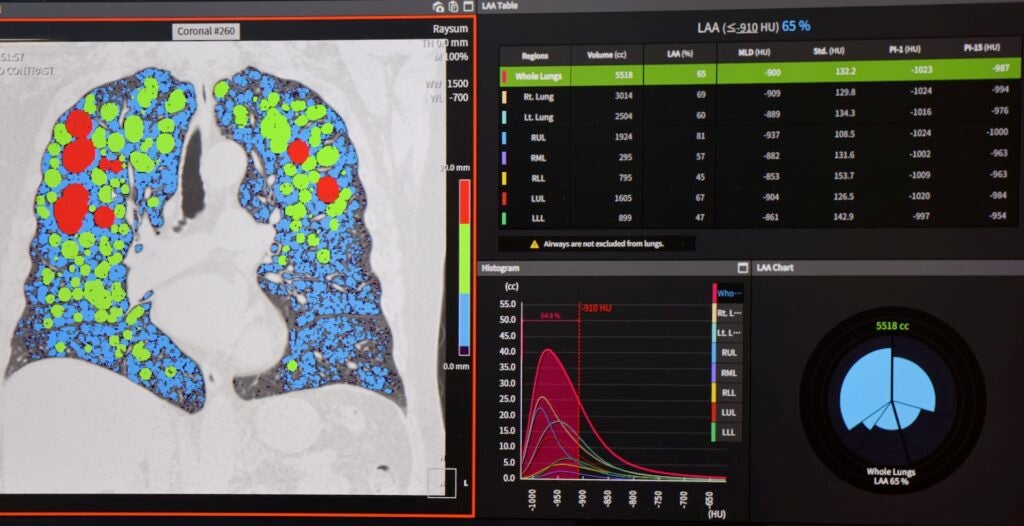

Sitting at his office computer at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, pulmonologist Dr. Gerard Criner pulled up black and white images from a CT scan of a patient’s lungs.

With a couple clicks, he generated an intricate and detailed 3D model of the organs using artificial intelligence software. He could now see the lungs’ airways, tissues and blood vessels, down to size and exact location.

This patient has emphysema, a chronic and progressive disease that destroys air sacs in the lungs and creates dead space or holes, making it difficult to breathe. Doctors sometimes remove damaged tissue in and around those areas to improve lung function.

“In this case, we’re looking for selective regions of the lung that we want to treat that are most diseased,” Criner said and pointed to bright red circular blobs representing the largest holes. “I can pretty much map out the airways that go to these regions so I can be selective in planning the procedure.”

With more precise diagnoses, earlier detection and new treatments, hopes are high for AI in medicine. But as Pennsylvania health systems and companies rapidly adopt this technology for both clinical and administrative uses, physicians, lawmakers and patient safety advocates are trying to figure out how to regulate these novel tools without quashing innovation.

“I think it can be a game changer for health care in general, safety of patients, for sure,” said Becky Jones, director of data science and research at the Patient Safety Authority in Pennsylvania. “But it can also introduce new safety risks that we’ve never seen before.”

Using AI to aid in clinical decisions, not as a substitute

At the Temple Lung Center, doctors and radiologists use an AI software called Coreline in CT analysis and lung cancer screenings.

The benefits are obvious, said Criner, who is director of the center and has been practicing for over 45 years.

The AI-involved scans and data tools have helped him and his colleagues assess the extent of someone’s disease faster and more thoroughly, predict risks, explore treatment plans and even catch extremely early signs of lung cancer that may have otherwise been missed.

“It’s more objective than the human eye to interpret things and you can quantitate things a little bit better,” Criner said.

But the AI software and tools don’t dictate clinical decisions or make any final treatment calls, he said. They are only meant to aid or supplement the medical expertise of the humans who use them — doctors, nurses, radiologists and other health care workers.

“It doesn’t replace other things that you do as a clinician,” Criner said. “To be able to talk to the patient, find out what’s important, do things in shared decision-making fashion with the patients.”

Pennsylvania lawmakers want to make sure it stays that way. With bipartisan support, they’ve introduced a bill that would set parameters for how AI should and could be used in different areas of health care.

“That’s where I think we need to take a step back and where in my role as a legislator is to say, what is our responsibility to the people of Pennsylvania in a technology that is autonomous and has the potential to change the fundamental relationship in how health care is delivered?” said state Rep. Arvind Venkat, prime sponsor of the bill.

State efforts in regulating AI and ensuring its safety

As an emergency physician in Allegheny County, Venkat shares in the excitement around AI and its potential, especially to relieve health care workers with time-consuming tasks like patient charting, medical documentation and assessing staffing needs.

But it also requires great scrutiny, he said. Could this evolving technology one day supersede humans’ roles in clinical decision making? Could it deny health insurance coverage for lifesaving treatments without any human intervention? Or leave the door open to new cybersecurity risks for sensitive patient information?

Pennsylvania has existing laws on health care ethics, patient privacy and data collection, transparency and informed consent, as well as consumer protections for health insurance, but they don’t specifically speak to AI.

“Right now, it is the Wild West when it comes to artificial intelligence, as to whether in the deployment of artificial intelligence, those laws are being followed,” he said.

The proposed bill would create a rule book for how health providers and companies could apply AI in clinical settings, the health insurance sector and in data collection, “without creating an onerous burden that would prevent them from continuing to innovate and apply artificial intelligence where it may be appropriate,” Venkat said.

Patients should be told when AI is involved in their care, he said, and a human should be responsible for any final decisions on treatment and health insurance coverage.

The bill also calls for AI tools and software that prevent bias and discrimination in health care settings, not reinforce or add to it.

Without legislation at the federal level to build on, Venkat said it’s up to individual states to address AI sooner rather than later.

“I think we have no choice but to move forward in this regard,” he said.

Independent, nonregulatory groups like the Patient Safety Authority are just beginning to monitor and assess AI in Pennsylvania health care systems and its impact on patients.

The authority looks for new and emerging issues that affect patient safety. Hospitals, nursing homes and health offices are required to report misdiagnoses, fall injuries, medication errors and other kinds of adverse events.

The number of safety reports that specifically mention the involvement of AI is small right now, Jones said, but she expects it will grow — not necessarily because the technology is becoming unsafe, but rather in the hopes that health care workers will become more aware of how and when AI is contributing to care.

But so far, early data show that AI is having more positive effects on patient care rather than negative.

“We don’t want to only focus on the negative. We want to see where it is performing well for patient safety, as well,” Jones said. “In those cases where there was an event that actually did occur, but the AI came along and somehow helped to identify it sooner, we want to know that.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.