A Chadds Ford homecoming for Jamie Wyeth retrospective [photos]

ListenThe house that Jamie Wyeth grew up in – an old farmhouse he later shared with this father, Andrew Wyeth, as studio space – is now preserved by the Brandywine River Museum, just down the road in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

As a publicly accessible time capsule, the museum arranged the living room to appear just as it did when the younger Wyeth, just 20 years old, was working on an commissioned, posthumous portrait of President John F. Kennedy.

It was also where he painted a portrait of a derelict man named Shorty, with a mottled face and dirty undershirt. That picture, included in a major career retrospective, helped make the young artist’s reputation as a highly skilled realist. Wyeth was 17.

“I had just gotten my driver’s license,” said Wyeth, now 68, revisiting the room. “I used to walk the railroad tracks for miles. I found him living in a shack along the railroad. I asked if he would pose. He had no idea what I was talking about.”

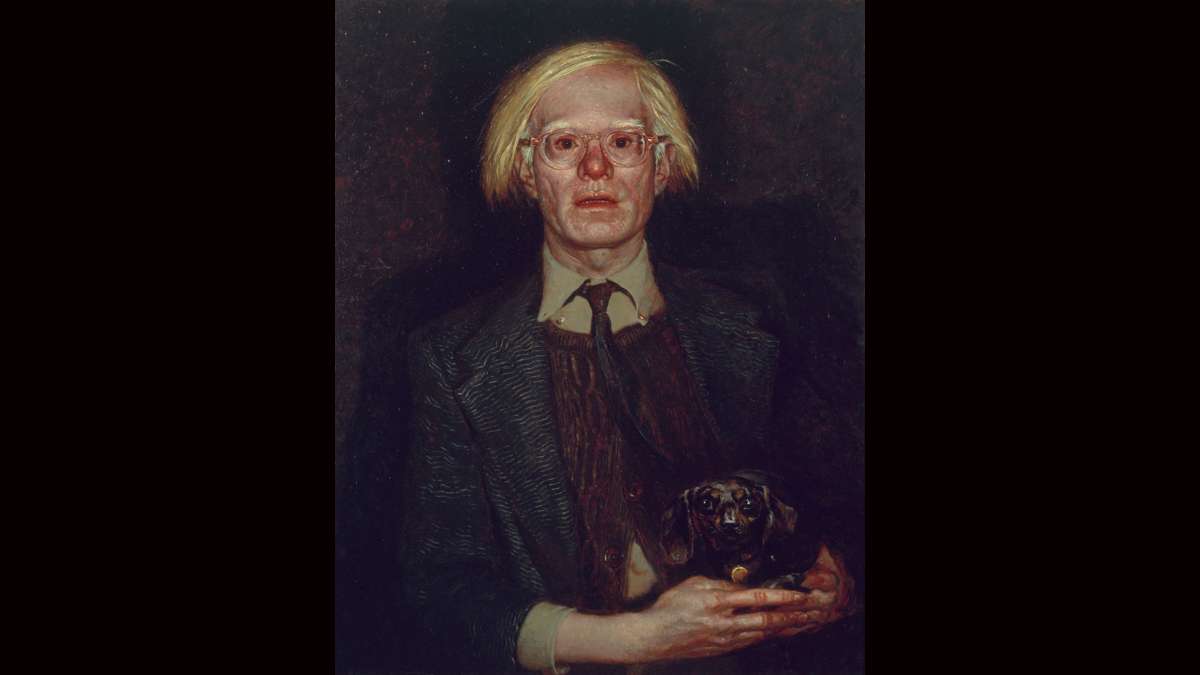

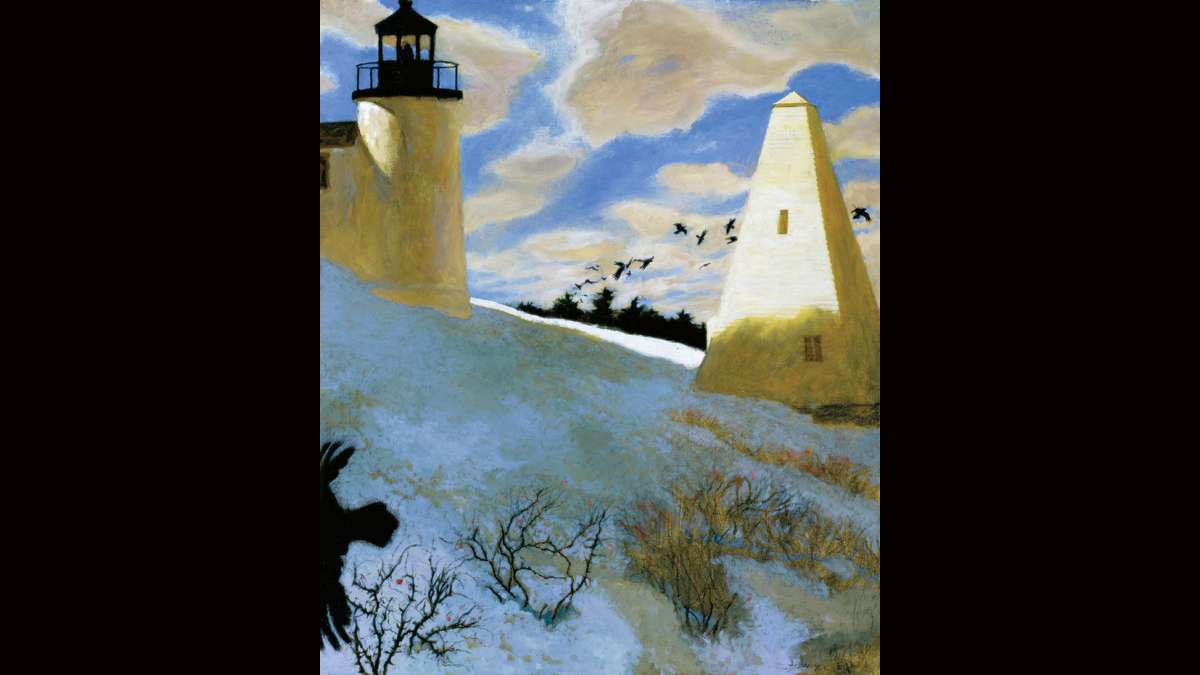

The show represents more than 60 years of work, from childhood doodles (Wyeth was home-schooled by his parents into an artistic life), to the period in New York City with Andy Warhol, to following Rudolf Nureyev around the world, to paintings of landscapes and curiosities on Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine, where Wyeth now spends much of his time.

The show was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, where it first appeared. Its next stop in Chadds Ford is a homecoming. The Brandywine museum is a repository of the Wyeth artistic dynasty – grandfather N.C. Wyeth, father Andrew Wyeth, aunt Carolyn Wyeth, and Jamie. The Brandywine iteration of the show will include some pieces from its own collection that were not in Boston.

“I find exhibitions of this size rather discomforting,” said Wyeth. “All the inadequacies jump out at me. Each of these paintings is a little obsession I have had. Once I’m finished, I don’t want to go back into it again.”

Wyeth has returned to some old obsessions during his career. He had spent a significant amount of time in the 1970s drawing Nureyev, “an extraordinary creature” who tightly controlled his image onstage and off.

“As a dancer, his image is his life,” said Wyeth. “I would be drawing a foot or something, and he would say, ‘No, foot more beautiful.'”

After Nureyev’s death in 1993, Wyeth returned to the subject. “I spent so much time drawing him, and I paint him with my eyes closed. I was able to go on with things I was not able to do while he was living,” said Wyeth.

The familiy connection

Wyeth’s career has been a careen, moving between subjects by whim and inspiration. He no longer does commissioned portraits, no longer paints for hire. He rarely travels beyond his homes in Pennsylvania and Monhegan. Like his father, Wyeth finds the most inspiration just outside his door.

“It’s hard for me to paint something I’ve never seen before,” said Wyeth. “I’m not interested in interesting trees or interesting-looking people. What I am interested in are trees that I know, or people that I know.”

Comparisons with his father and grandfather – two giants of American art – have shadowed Wyeth for a half-century. The Brandywine show will be literally steps away from one of the largest collections of work by Andrew and N.C. Wyeth.

“I can’t help but be informed by it,” said Wyeth, who sees his work more connected to his grandfather, famous for iconic illustrations for adventure novels including “Treasure Island” and “The Last of the Mohicans.”

His father, who made rustic egg tempera paintings of farming scenes steeped with poetic meaning, is “misunderstood.”

“He was a very odd painter in this crystalline, airless world,” said Wyeth during interview, recorded in his childhood home. “And they call him a realist. He’s no more realist than that microphone.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.