Helping SEPTA get around better

Graphic from DVRPC’s study Speeding up SEPTA (2008)

Aug. 18

By Anthony Campisi

For PlanPhilly

SEPTA bus riders may be seeing faster rides along city routes over the next year.

The Nutter administration plans to convene a Transit First panel that will tackle slow bus travel times and aim at reducing congestion along commercial corridors, according to Andrew Stober, director of strategic initiatives in the mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities.

Stober said that the administration is in talks with SEPTA and city and state agencies like the Streets Department, Parking Authority and Pennsylvania Department of Transportation to convene the committee in October.

The goal of the panel will be to “identify where the opportunities exist to improve travel times,” Stober said, adding that “the city is going to be working with SEPTA in the next year to closely look at new routes.”

The Transit First panel will select routes and commercial corridors throughout the city where changes such as consolidating bus stops and introducing limited-stop bus service would cut down passenger travel times.

Philadelphia’s current bus and trolley network leans more toward providing riders with the convenience of frequent stops over providing reliable and fast service, Stober said, adding that the Transit First panel will try to better balance those competing interests.

Any successful effort at increasing bus and trolley travel time could yield big dividends for both SEPTA and riders. The faster buses and trolleys travel along their routes, the fewer vehicles SEPTA will need running at any one time in order to provide the same level of service.

A report released last year by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission calculated that it cost SEPTA $142,900 to operate a peak-hour bus and $279,200 to operate a peak-hour trolley.

The effect of even small increases in vehicle speed would be significant. The same report, titled Speeding Up SEPTA, calculated that an increase of only 1 mph in City Transit Division bus service “would yield roughly $13 million in annual savings” for the agency.

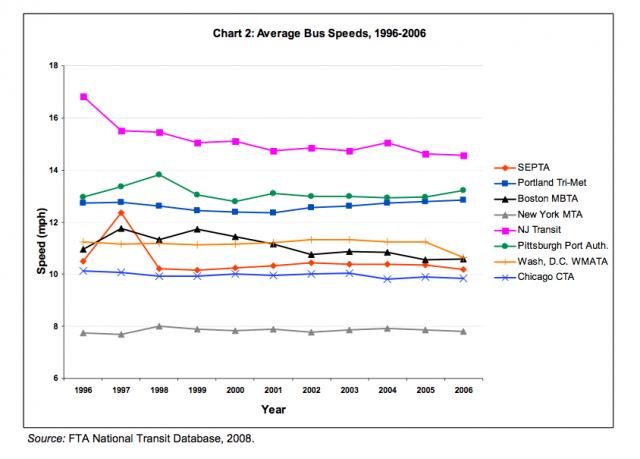

And clocking in at a little above 10 mph, SEPTA buses are the third-slowest on average among major transit agencies surveyed by the DVRPC. (The New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority came in last at an average below 8 mph, in part because of the dense urban areas it serves.)

One way of speeding up service that the Transit First panel will be considering is bus stop consolidation. National guidelines call for bus stops to be placed about a quarter-mile apart in urban areas to minimize travel time while still retaining accessible service.

In many Philadelphia neighborhoods, including Center City and surrounding areas, buses stop at every corner along their routes.

Though this effectively provides door-to-door service for many Philadelphians, it also has the effect of lengthening travel time. A stop consolidation project in Los Angeles cited by the DVRPC found that a 71.4-percent reduction in bus stops along a bus route led to a 9.25-percent reduction in running time.

The Center City District, in a report released last year entitled Managing Success in Center City (http://www.centercityphila.org/docs/2008CCDcongestion.pdf) called on SEPTA to study placing bus stops on every other corner in Center City as a way of speeding up bus service to provide travelers “a significantly faster cross-town alternative” to other means of transportation.

Ahmed El-Geneidy, a professor at the McGill School of Urban Planning who studies bus stop spacing, explained that every bus stop placed along a route increases total travel time by about 5 to 10 seconds — even when no passengers are present. Bus drivers who have to prepare to pick up passengers at a stop are kept from accelerating as much as they could.

“Stopping at every single block is wrong,” he said.

However, to get the most out of stop consolidation, SEPTA will have to remove stops that riders use. The goal of stop removal, El-Geneidy said, is to consolidate riders who are spread out along bus and trolley routes and concentrate them at fewer stops with higher use.

Though it may be difficult to convince riders to give up the convenience of stops on every block, agencies that have succeeded in consolidation have reported high levels of customer satisfaction.

In fact, customers report greater travel-time savings than consolidation actually provides. In a paper currently under peer review, El-Geneidy found that riders in Montreal “felt savings up to 10 minutes for trips even though their savings were a minute and a half.”

At the same time, transit agencies have to be flexible in their consolidation efforts, El-Geneidy said. Elderly and disabled ridership patterns have to be taken into account so that stops and areas frequented by people who have trouble walking long distances won’t be affected.

The most difficult problem to solve when it comes to measures like stop consolidation, he said, is political. Riders and businesses frequently protest the perceived inconvenience of having fewer stops.

David Hull, a service planning supervisor at the King County Metro in Seattle, agrees. His agency has undertaken bus consolidation along several routes and has had to face down community opposition.

“A lot of people take removing stops as a take-away,” he said.

Though stop consolidation, when done right, doesn’t need to affect many riders, it’s often difficult for transit agencies to convey this fact, Hull said. Those who feel slighted by the proposed changes are usually more effective at mobilizing than transit riders who will see their travel time go down.

As a way of dealing with public concerns in a single stroke, the King County Metro is considering a system-wide stop consolidation process to replace the more scattered efforts that have taken place in recent years. As part of that, Hull said the agency is considering instituting a formal appeals process to allow riders who disagree with any changes a space to air their grievances.

The Transit First committee won’t be the first such effort to improve service by the city and SEPTA.

The city’s first Transit First project was completed in 2006 along the Route 52 bus. It discontinued two stops and moved 27 others to the far sides of their intersections.

Moving bus stops to the other side of intersections, while not “a silver bullet” for decreasing trip time, according to Stober, allows buses to accelerate and decelerate more efficiently. The DVRPC said that moving the 27 stops resulted in total time savings of more than 5 minutes.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.