West Nile: A forgettable virus with unforgettable consequences

The virus seems harmless, because most people who contract it don't show symptoms. But that doesn't mean that it can’t cause the body serious harm, or even prove fatal.

Listen 6:37

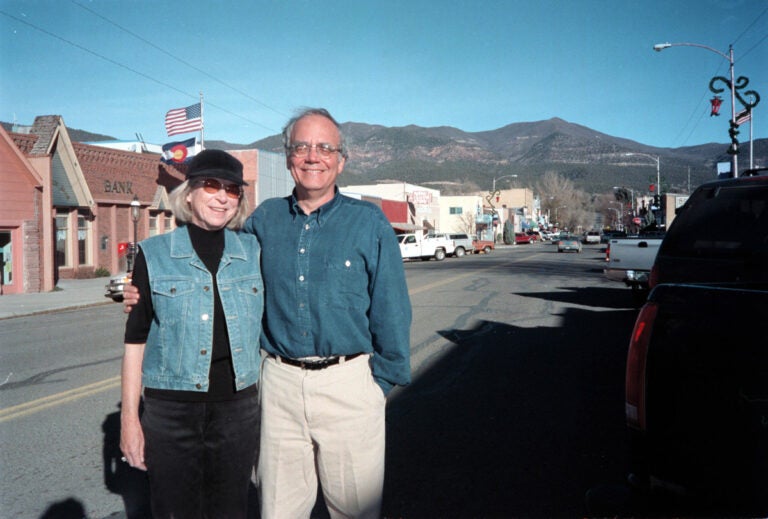

Ed Marston died of West Nile in 2018. He and his wife, Betsy, bought the High Country News, a well-known magazine across the West, in the early 1980s. (Photo by Cindy Wehling/courtesy of High Country News)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

All summer, the small western Colorado town of Paonia has free music nights at its downtown park. It’s always packed with families camped out on blankets, surrounded by food trucks and beer stands. And always, there’s a table with free mosquito repellent, which often goes unused.

That might sound like no big deal, but the mosquito-borne West Nile Virus has been active here for years. It’s killed more than 2,000 people in the United States since it was discovered in this country in 1999, and it’s left many more with serious disabilities. But since most people who get West Nile show few or no symptoms, folks often don’t think about it — until they have to.

I asked concert-goers about West Nile on one of those beautiful Paonia evenings last year. Most knew about the virus, but were not concerned.

Drew Henry was visiting from Arizona, from an area where West Nile has been found.

“Isn’t that like worrying about getting hit by, like, a meteor or something?” he said, before breaking into laughter. “It’s like, should I always be walking around with a hard hat on?”

Janet King, a local, told me she knows four people who’ve contracted West Nile, including her husband. But she refuses to live in fear of it because mosquitoes are ubiquitous.

“Which is why I think people don’t want to acknowledge what kind of damage it does,” she said, “because you can’t do anything if you have it, and you can’t keep a mosquito from biting you.”

Health officials strongly disagree, and stress using approved insect repellent, covering up, and even avoiding the outdoors at dusk and dawn.

A few months after that concert series wrapped up, West Nile’s 2019 toll on rural Delta County would become clear. It had registered 33 cases, more than twice that of any other county in the state. Two people died.

Ken Nordstrom, who heads the Delta County Department of Environmental Health, thinks these grim numbers could be fought with a countywide approach to eliminating mosquitoes.

“We need it! We need it!” he said, unequivocally.

Such an approach would include getting rid of standing water, where mosquitoes breed, as well as spraying, which is still controversial but has become less so as it’s become more targeted. All of that would require the approval of voters, however. Right now, only portions of the county have any mosquito control at all, and Nordstrom believes it will take a grassroots effort to change that. The issue has to feel important to people, he stressed. It has to feel personal.

He can think of one place to start.

“Oh, I think stories,” he said.

Subscribe to The Pulse

Stories of West Nile’s victims that show this can be a real and serious threat. Stories of people like Ed Marston, the former publisher of the High Country News, a well-known magazine in the West.

In summer 2018, his wife, Betsy, could see Marston wasn’t well. She remembers him feeling “tired and confused and listless.”

He had recently had a successful heart bypass operation and was recovering well. He was even back to hiking two miles a day through the wilderness he loved.

But all of a sudden, his body went downhill.

“And then finally, he could barely walk, and that’s when we went to the ER,” Betsy Marston said.

By the time the test results came back positive for West Nile, the virus had been eating away at Ed Marston’s body and mind for a little more than a week. He shook uncontrollably. He was practically comatose.

Soon, he died.

“West Nile disease is, is brutal,” Betsy Marston said. “You suffer. He suffered.”

West Nile can cause inflammation of the brain, seizures, and paralysis. There is no vaccine and no cure.

Betsy Marston is now part of a local survivors group. The goal is to support those affected by West Nile, and to warn everyone else.

John VanDenBerg is one of those survivors. He was also a longtime friend of Ed Marston’s. On the day of Ed’s funeral, he collapsed in his living room.

“And was unconscious on the floor and ended up semiconscious for a couple weeks, paralyzed,” he recalled.

VanDenBerg also had West Nile. He initially lost 30 IQ points. He needed a wheelchair. He’s since started that local survivors group. He’s also a member of a national group, thousands of people strong. He tells his story at public meetings and local organizations, wherever folks will listen.

VanDenBerg recently stopped using a walker after more than a year. He knows he’s one of the lucky ones, and not just because his body and mind are coming back.

“I had friends, I had relatives, I had support, I had financial abilities,” he said. “If you don’t have any of those things, try to imagine all of a sudden you can’t walk and your arms don’t work and your brain’s going haywire.”

He can see people pay attention when they hear his story, but he knows it can be tough to truly believe in this danger. It was the same for him.

“Before I got West Nile, when I looked at my area, I would see nothing but wonderfulness,” he said, with a knowing smile. “Now I look at my area and think, it’s wonderful. It’s beautiful. But boy, I better be careful.”

Because even though the odds are minuscule, he now understands how much a life can change from one mosquito bite.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.