‘They see me as a role model’: Black teachers improve education outcomes for Black students

Black students who are exposed to Black teachers by third grade are 13% more likely to enroll in college, research shows. This is called the role-model effect.

Listen 5:58

Aaron Taylor (far left) at the Erie Otters Hockey Club in Erie, PA after his students performed the National Anthem. (Courtesy of Aaron Taylor)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

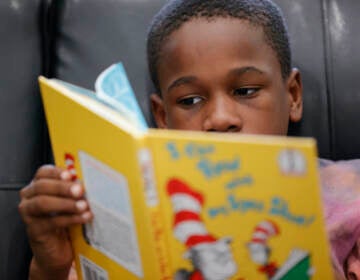

In second grade, Noah Reilly was assigned to do an immigration project. He and his classmates had to write short papers about their ancestors’ journeys to the United States and make dolls that represented their families’ stories. But Noah had a feeling his doll would look different.

“My mom said that I would probably be the only one with this [doll], and I was the only one,” Noah said.

For his project, Noah wanted to tell the story of his mother’s family, who are Black. He is a multiracial child who attends a school in the suburbs of Philadelphia where Black children make up only 5% of the student population. Noah’s teacher was white.

“I think it was hard for the teacher to understand why the project was an issue, that not everyone has an immigration story,” said Monet Reilly, Noah’s mother. “There were obviously a large group of people who came here as slaves. And not as willing immigrants.”

Reilly said the project forced her to discuss slavery with Noah, something she wasn’t ready to do. And despite several attempts to raise concerns with his teacher, she was met with general dismissiveness.

“She told me, ‘Well, you know the Irish came here as slaves too,’ as if that somehow made it better that I had to explain to my then 7-year-old what slavery was and why it not the same as immigration,” Reilly said.

At the time, Black teachers made up only 1% of Noah’s school district. Reilly said that if there had been more teachers of color in his school, someone could have looked at the project and been able to intervene earlier.

The Tennessee Star Experiment

Noah is in fourth grade now, and he has never had a Black teacher until this year. This absence of Black teachers is a reality for many Black students all over the country. For decades, researchers and policy makers have tried to understand whether a race match between teachers and students has positive effects on educational outcomes: meaning, if a Black student has early exposure to a Black teacher, is the student more likely to perform better on standardized tests, graduate from high school, and matriculate to college?

Tennessee paved the way for researchers to answer this question for years to come. In the 1980s, the state was interested in passing policies that would control and minimize class sizes in public schools. But it wanted to have rigorous evidence that this would have positive effects on student outcomes. So it authorized a massive educational experiment in the mid-1980s called the Tennessee Star Experiment, one of the most critical experiments in educational research history.

Seven thousand students in 79 schools were recruited, and they randomly assigned the students in those schools to either small classes, regular-sized classes, or regular-sized classes with a full time teacher’s aide. One of the key things they did that would later give rise to a wide set of research papers is that they randomized the students and the teachers to those conditions and to one another — meaning that randomizing for class size meant teacher race was randomized as well.

Cassandra Hart, an associate professor of education policy at University of California, Davis, said earlier studies used this data set to prove the short-term impact of race-congruent teachers on things such as next year’s test scores or this year’s discipline. But in 2018, Hart and a team of education policy researchers used the Project Star data to explore the long-run impact of having a Black teacher as a Black student.

“Earlier studies had shown … Black students matched to Black teachers saw modest benefits in terms of their performance on standardized tests,” Hart said. “And what we wanted to look at is whether there were longer-term outcomes. So if you’re matched to a Black teacher in your elementary school years, does that still matter down the line for things like your high school graduation, and ultimately your college enrollment outcomes.”

The role-model effect

Hart and her colleagues discovered that Black students who were randomly matched to Black teachers did, in fact, have better long-run outcomes. Black students who were exposed to Black teachers by third grade were 13% more likely to enroll in college. If kids had two Black teachers by third grade, Hart said, the likelihood of college enrollment jumped to 32%. Hart and her colleagues call this the role-model effect.

Subscribe to The Pulse

“One possibility is that there may be role-model benefits, so having a Black teacher in front of the class, being a subject-matter expert, might act as role model and increase children’s long-term aspirations for themselves,” she said.

According to Hart, there’s also good evidence in the social science literature that students are responsive to the expectations that we hold for them. Research shows that Black teachers tend to hold slightly higher expectations for their Black students. And Black educators are more likely to use references or examples that tap into the lived experience of their Black students.

Constance Lindsay, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s School of Education, was also a contributing researcher to the paper on the role-model effect. Lindsay has spent a great deal of her career thinking about racial achievement gaps and the particular policies and practices that might help close them. She said one of the policy motivations for focusing on Black students in the study is that they have higher dropout rates and lower college attendance rates than their white counterparts. Lindsay says low-income Black boys saw the biggest boosts in educational outcomes from being paired to a Black teacher.

“We see huge jumps for them, and there’s lots of societal gain to be had from that,” Lindsay said. “There’s been extensive work on the cost-benefit of intervening with children earlier rather than later in life. So it makes sense to do some of these relatively low-cost investments of increasing [Black boys’] exposure to Black teachers.”

Lindsay and her team also looked at whether there were benefits for white students who were matched with Black teachers. They found that Black teachers had little to no effect on white student education outcomes, which she said further proves the impact of the role-model effect for Black students.

“Most white children are already race-matched to their teacher,” Lindsay said. “And so what this suggests is that having a greater representation of Black teachers in the workforce benefited Black children without any negative effects for the white children we were looking at as well.”

‘They see me as an advocate for them to succeed’

Aaron Taylor is Black and a music teacher at a middle school in Erie, Pennsylvania. Neither of his parents graduated from college, and he didn’t always think that college was an option for him. But growing up, music was his source of solace.

“I’ve always had a lot of energy, and music was a way not only to calm the energy I had but to put it somewhere,” said Taylor, 26.

From fifth grade onward, Taylor attended performing arts schools in Pittsburgh. And during those years, he developed a close relationship with his African American trombone instructor, Carl Jackson, who gave him a key piece of career advice toward the end of high school.

“It wasn’t until my 11th grade year where I sat down and I talked to Mr. Jackson and I told him I want to go to school to be a music performer … and he said have you ever thought about being a teacher?”

Inspired by Mr. Jackson, Taylor went to college to become a music teacher. At the middle school where he teaches now, only 11% of the teachers are Black, though almost half of the student population is. Taylor said his students of color depend on him in a different way, and he doesn’t want to let them down.

“They see me as a role model, they see me as an advocate for them to succeed, they see me as someone who’s made a way when there wasn’t a way,” Taylor said.

In his classroom, he likes to create a sense of community, where all cultural perspectives are celebrated. Taylor begins each class with what he calls a bell ringer, a song that’s popular on the radio at any given time. Sometimes, it’s hip-hop, sometimes it’s pop. But the ultimate goal is to bring student interests into the classroom. At his school, 17 different languages are represented, and 25 different countries.

“I do have units where I talk about music from different parts of the world, so for the students who are coming from these parts of the world, they can also provide a bit of their own authentic experience,” Taylor said.

His students’ experiences become a tool for teaching and learning. Lindsay, of UNC, said that’s effective.

“Instead of viewing what students bring to school from a deficit orientation, you’re really viewing it from an asset-based orientation and trying to build on their culture instead of viewing it as outside of the mainstream,” Lindsay said.

Taylor remembers finishing his master’s degree in 2018, and his school shared the news on its social account. Many of his students saw the announcement and flooded him with questions.

“They were like, ‘Mr. Taylor, I heard you graduated, you finished something, what was it?’ And that allowed me to open up that conversation,” he said.

For Taylor, every opportunity he gets to stand in front of his students and teach is one more chance they get to see what’s possible for themselves.

“When you go to a classroom where you feel you are wanted, desired, and respected, you feel a part of it, you feel a part of the community.”

Support for WHYY’s coverage on health equity issues comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.