Philly art exhibit examines what to expect when you’re expecting privacy

A digital artist turns Philadelphia's Icebox gallery into an immersive interpretation of 4th Amendment privacy laws.

Listen 2:57

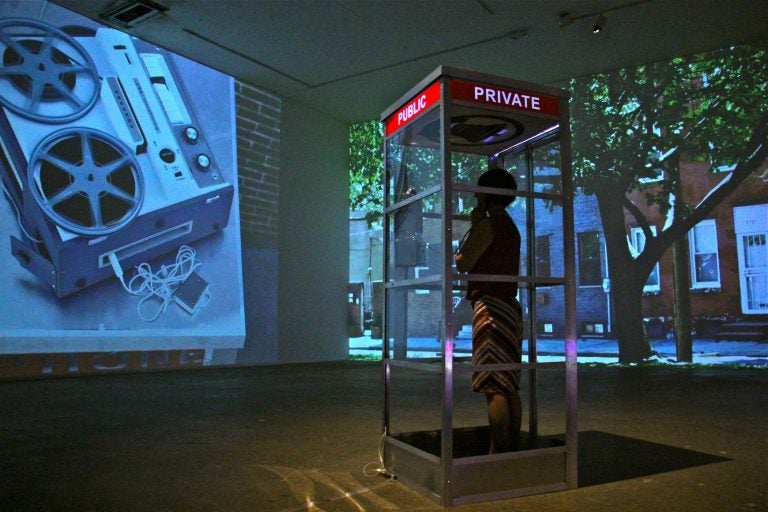

Lisa Marie Patzer's immersive installation at the Crane Arts Building, "A Reasonable Expectation of Privacy," looks at changing technology and its impact on Fourth Amendment rights. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

If you take a minute to sit on a park bench to watch the world go by, you see a lot of things. People hurry past with cell phones glued to their cheeks. People with armloads of shopping bags. Some people shouting at each other; some talk quietly with their heads bent toward each other.

How can you know if you’re watching a crime?

At the Crane Art Building’s Icebox, a former cold storage warehouse converted into a huge art installation gallery in Kensington, visitors can sit on a park bench and watch an enormous video projection, 75 feet wide by 25 feet high. It’s so big that the figures in the video seem life-size. It feels like you are spying.

The panning video shot tracks a man walking along the edge of a park toward a phone booth. Inside the booth, he makes a call. You can put on headphones to listen to his conversation. He’s placing bets.

The man is an actor portraying Charles Katz. In 1965, the FBI placed a microphone on top of a phone booth where it suspected Katz was placing illegal bets. He was, indeed, committing a crime and fined $300.

In 1967, the Supreme Court overruled his conviction, deciding that conversations inside a public phone booth constitute a “reasonable expectation of privacy.”

“It was the first time the 4th Amendment was granted to someone having a conversation in a public space,” said artist Lisa Marie Patzer.

“A Reasonable Expectation of Privacy” is her artistic response to the Katz v. United States case and the interpretation of privacy laws in the digital age. It runs through Sunday, July 29.

The installation is immersive. Visitors can not only sit on the bench in active surveillance, eavesdropping on wiretaps, but enter the phone booth and listen via the handset to a legal analysis of privacy law rulings.

A phone booth is a relic of a different age. When was the last time you closed its bifolding door behind you, if ever? Despite the fact that some of its Plexiglass panels are conspicuously missing, you feel like that cramped interior is private. Like Superman, you might believe this is a reasonable place to change clothes.

“A lot of the justices asked questions like, ‘What was the size of the phone booth?’ ‘Did he have the door open or closed?’ ‘Was he speaking in a low tone of voice?’” she said. “They were concerned about that perception of privacy.”

When the Founding Fathers drafted the 4th Amendment prohibiting unreasonable search and seizure, privacy was understood in physical terms: your person, your property, your papers. Police cannot forcibly enter your home without cause.

Now, of course, to seize evidence of a suspected crime, police do not need to be on your property. They don’t even need to be on the planet. The most recent SCOTUS decision involving the 4th Amendment, last month’s Carpenter vs. United States ruling, concluded that police cannot gather location data from the GPS in your cell phone without a warrant.

As a video and new media artist, Patzer often uses electronic equipment very similar to surveillance technology. She likes to put you in the hot seat.

Another part of the exhibition invites visitors to text a password to a particular account, and in response, receive background information – via text – of other Supreme Court privacy decisions.

But as soon as Patzer’s automated text bot (you can see its raw circuitry right there in the exhibition space) receives your text, it has collected bits of metadata about you and your phone.

“I wanted to offer something akin to what we’re actually dealing with today,” said Patzer. “We’re constantly giving up our data and we don’t think about it. We don’t read the fine print and we’re not sure what we’re agreeing to all the time. That’s territory in which the 4th Amendment has not been totally fleshed out.”

Patzer promises she will only use that data to send out information about her next exhibition, whenever that happens.

“A Reasonable Expectation of Privacy” was made specifically for the Icebox — Patzer was its first video artist in residence — and will not easily translate to any other space. She is thinking about making a more portable version that can be contained entirely inside a phone booth.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.