Pew Report: Philly’s poor have been stuck in the inner city, separated from suburban job growth

The report compares Philadelphia’s poverty statistics with the nation’s ten largest cities and the nation’s ten poorest cities. Philadelphia is the only city in both lists.

Listen 5:02

(PlanPhilly)

On Wednesday, Pew Charitable Trusts released a new study exploring the city’s infamous status as America’s poorest big city.

“We know that Philadelphia is the poorest big city in the United States,” said Octavia Howell, a researcher with Pew’s Philadelphia Research Initiative and one of the study’s lead authors. “Pew’s goal with this research was to get beyond the headline poverty rate of 25.7 percent and understand poverty in the city more fully, in terms of demographics and geography over time and see how this compared with other cities.”

The report compares Philadelphia’s poverty statistics with the nation’s ten largest cities and the nation’s ten poorest cities. Philadelphia is the only city in both lists.

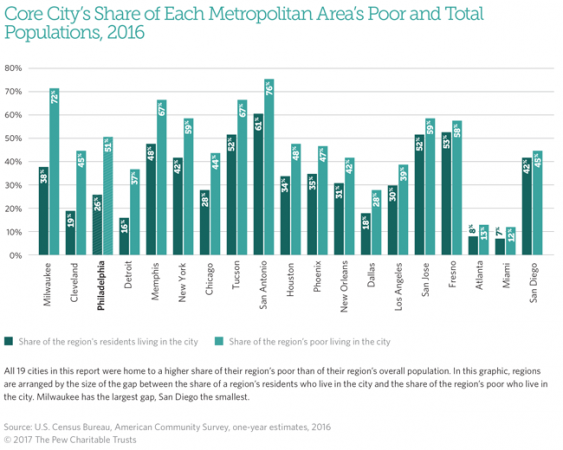

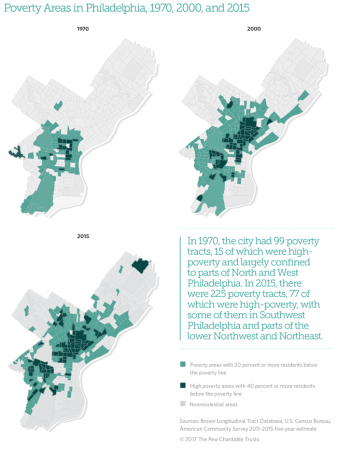

It finds that Philadelphia’s poverty is more concentrated than many other cities. While the city’s poverty rate is appallingly high, the region’s rate of just 12.9 percent is only slightly above the national average of 12.7. Other cities suburbs have seen their poverty rates tick up as rising inner city property values have pushed the impoverished beyond city limits. But Philadelphia was once a city of 2 million, meaning the city itself has retained a large stock of affordable homes. Housing in Philadelphia is cheaper than it is in the suburbs. Additionally, a relatively high 28 percent of poor households in Philadelphia own their homes — this percentage discourages more of the city’s impoverished from moving. To make matters worse, many Philadelphia suburbs tightly regulate land use, which makes it harder to build (and build affordable housing in particular).

Transportation also plays a role: Philly has a good transit system, and the cost of car ownership here is higher than it is most other places. While SEPTA and PATCO offer suburban transit options, they simply cannot compare to the size and frequency of the city transit network.

Cheaper rent and better buses, alone, don’t explain why the region’s poorer residents remain in the city. But once you add jobs to the mix, the picture becomes complete.

Since 1970, the total number of jobs in Philadelphia has fallen 24 percent, while the number of jobs in the suburbs went up 110 percent.

“The key driver of poverty is a lack of jobs and good jobs,” Robert DeFina, professor of sociology at Villanova University, is quoted saying in the report.

Since 2010, Philadelphia itself has seen very modest job growth. But in the decades prior, all of the employment gains were in the suburbs, largely inaccessible to the region’s impoverished.

Not only that, the kind of jobs created in Greater Philadelphia in the last half century have meant little to those living below the poverty line.

The report notes that, since 1970, the region’s number management and professional positions — jobs that usually require a college degree — grew 85 percent. But only 13 percent of the city’s poor residents have a bachelors degree or better. “Another sector, service employment, which includes food preparation, grew by 56 percent,” the report goes on to note. “Most of this work does not require advanced education, and the pay is relatively low. Of the 10 sales and service job categories with the most employees in Philadelphia and Delaware County in May 2016, all had median annual earnings below $29,250.”

Not any job will lift a person out of poverty. According to the report, 30.1 percent of poor adults in Philadelphia reported working in 2016. In past generations, low-skill manufacturing jobs paid well enough to provide a middle-class lifestyle. But by 1990, the service sector had replace manufacturing as the top employment sector in Philadelphia and many other rustbelt cities.

Unlike some of the other poorest cities, like Cleveland and Detroit, Philadelphia has seen a modest renewal since 2006. After a half century of decline, Philadelphia’s population started to grow again. Similarly, Philadelphia’s poverty rate has leveled off since 2006, only increasing 0.6 percent in the ensuing decade.

If the city continues to add residents and jobs, we can expect to see the poverty rate start to decline in coming years. But that won’t necessarily mean good news for Philadelphia’s 400,000 residents living below the federal poverty line. The poverty rate is a fraction, which can be moved by changes to the numerator (number of impoverished residents) or changes to the denominator (total number of residents). As the city’s population of white-collar workers expands, the denominator will grow, reducing the poverty rate.

The poverty rate will also decline if the numerator shrinks, the report notes. But why it might shrink matters. As the report’s authors put it: “Some individuals do manage to move out of poverty in Philadelphia, but many others are hindered by an economy that largely generates two kinds of jobs: low-paid service jobs that do not support a family or high-salary positions that require skills and training that most poor people lack or have a difficult time obtaining.”

That last line could describe the poor nearly anywhere in America today, from the biggest coastal cities to the smallest farm towns. Philadelphia isn’t alone, but that’s small comfort. No one city can tackle the problem of an economy which continues to automate relatively high-paying, low-skill work at a rapid pace, only to replace those jobs with white collar work or minimum wage gigs.

The Philadelphia region can control its transportation network and zoning policies to lower barriers to the few good blue collar jobs that do exist for those concentrated thousands struggling to escape poverty. But Philadelphia’s failure to address a fundamental fissure in the nation’s economy should not be the city’s enduring shame. Philadelphia’s poverty rate is egregiously high, and has remained so for years. But that is not the city’s fault, it is society’s.

The full report is available on Pew’s website, here.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.