Meet a scientist who actually likes mosquitoes

Naturally, she swats at them from time to time, but it’s her job to get to know the little biters better.

Listen 7:24

Entomologist Autumn Angelus prepares to set out on a mosquito collecting expedition at Elmer Lake Wildlife Management Area in Salem County, New Jersey. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

Entomologist Autumn Angelus kills mosquitoes that try to bite her, just like the rest of us.

But before she slaps, she’ll look to see what kind it is first. And she is always investigating.

“I’m always looking for mosquito larvae, I’m always looking for mosquitoes. Even when we went to Disney World, I was checking the bromeliads for mosquito larvae.”

Most people hate mosquitoes. Among the animal kingdom, they are responsible for the most human deaths, killing tens of thousands of people a year through diseases like malaria and dengue fever. The German poet Goethe once said that mosquitoes made him doubt God’s goodness, because how could a benevolent and all-powerful deity create a mosquito?

Angelus doesn’t see it that way.

“Everybody thinks it’s crazy, but I love my job, and I love what I do, and mosquitoes keep me employed and I find them very fascinating.”

She studies insects and specializes in mosquitoes, but part of her job is to keep them in check.

Angelus works for Salem County Mosquito Control in New Jersey, and during a stop at the Elmer Lake Wildlife Management Area back in early March, she looked for mosquito larvae in some dirty, tea-colored water sitting stagnant on the ground.

She almost always has an aspirator, a mosquito-catching device, in her purse. On this particular day, she also had a dipper, a plastic ladle connected to a long stick. She scooped up some of the water and peered inside for wriggling young mosquitoes. She also collected some water with mosquito larvae in a plastic bag, so she could try to raise them back in her lab.

Another part of Angelus’ job is to go through whatever gets caught in various insect traps in strategic locations, to stay on top of which mosquitoes are active.

“It can get very tedious and messy, because the other insect scales tend to get everywhere. So sometimes you’re blowing your nose and you have insect parts that come out,” she said.

Her friends might think she’s eccentric, but kids don’t. Angelus sometimes talks about her work at schools.

“I relate insects and metamorphosis to Pokémon … and I basically get to tell them that I’m a real-life Pokémon trainer, because I’m always chasing after insects and collecting all their different stages.”

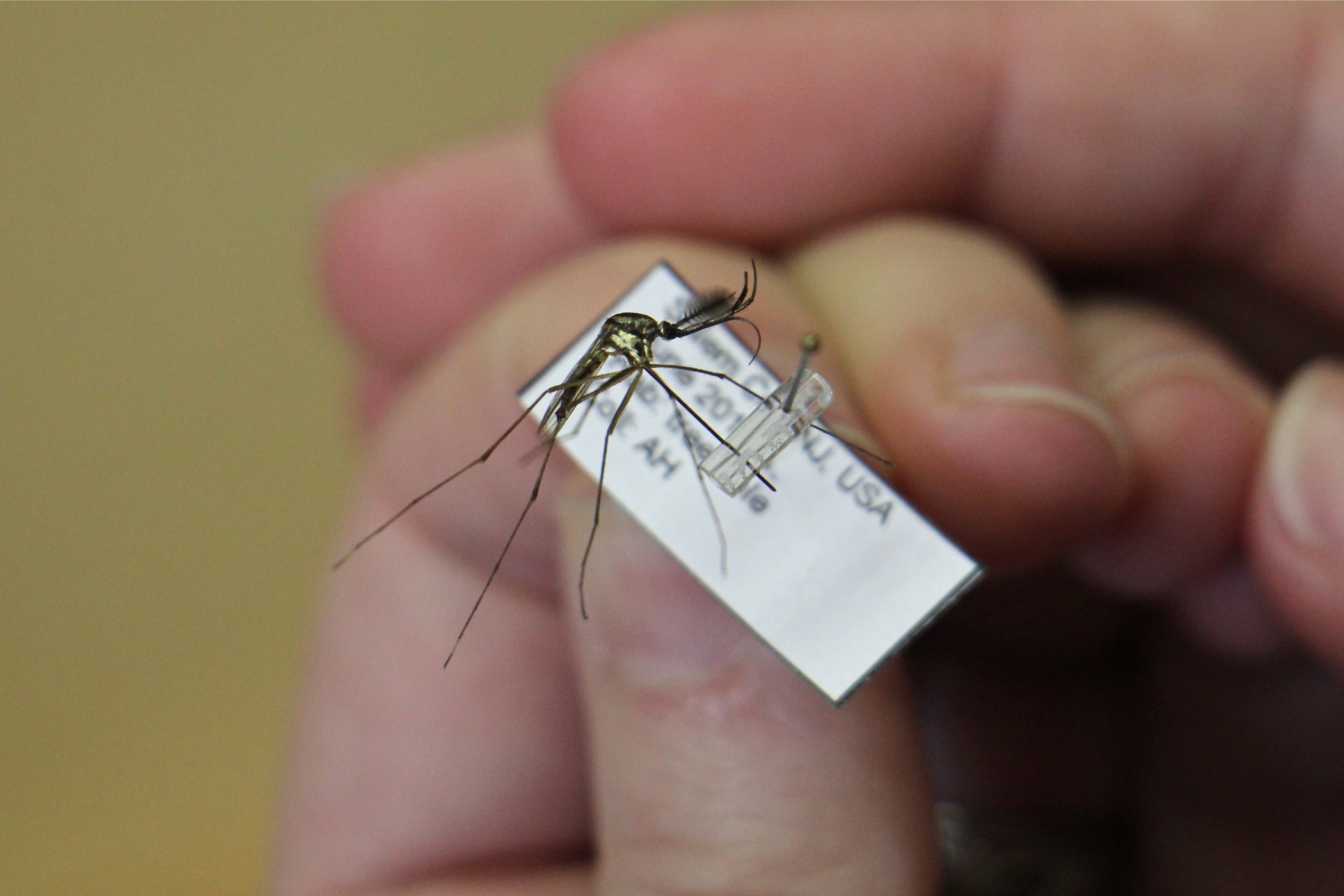

Angelus has been working in mosquito control for more than a decade, since she was 18. That’s when she met the one — the mosquito that got her hooked on mosquitoes: toxorhynchites rutilus.

“That is my favorite, and, yes, she’s a very good mosquito,” Angelus said. “Its common name is the elephant mosquito, and that’s because of this long curved proboscis, so [it] kind of looks like an elephant trunk.”

That shape means these mosquitoes do not drink blood.

“The first time I saw an adult and its brilliant colors, its green and yellow and blue colors, I was just amazed,” she said. “So after that, I kind of went searching for them, and every time I found one, I would keep it, and I would rear it out.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

At the time, Angelus worked with the entomologist to feed their larvae and raise them into adults.

“I never really grasped the gravity of how wonderful they are … that took me until I was really caring for them and trying to colonize them, because they’re so specific and they’re so picky.”

For example, these mosquitoes mate while they fall through the sky. The female lays her eggs one at a time by dive-bombing them into holes in trees.

Angelus and another entomologist in Texas are trying to raise these mosquitoes because their larvae will actually eat other mosquito larvae, so they could potentially be used to kill the mosquitoes that spread diseases such as West Nile Virus or Eastern Equine Encephalitis.

Some mosquitoes are beneficial: The larvae of Toxorhynchites mosquitoes are predators of the larvae of other mosquitoes (and other aquatic inverts) and the adult females do not blood feed. They often occupy the same container habitats as exotic Aedes sp. #FLMosquitoWeek #UFbugs pic.twitter.com/OIehjTzXpa

— Lary Reeves (@BiodiversiLary) April 21, 2020

And that’s her job too: to test mosquitoes to see which viruses they have, and keep the disease-spreading mosquito populations down.

“Most people in mosquito control are very passionate about what we do, and it’s just unfortunate that we kind of get ignored — we’re like the red-headed stepchild of the government departments. Even just trying to get the word out there that we exist is difficult.”

She was disappointed when the NBC-TV show “Parks and Recreation” did not have someone from mosquito control.

“I was really hopeful … my husband always says that I’m the Leslie Knope of mosquito control, because I’m, like, always so excited about it.”

Mosquitoes, of course, have been living in the marshlands and plains of New Jersey since long before any humans came there. They’ve figured out every place where they could live. And that’s partly why Angelus finds them interesting.

“Mosquitoes have been around for so many millions of years that each one occupies a specific niche habitat, and they’ve just been really good at finding every niche habitat that they possibly can. There are several species that occupy … artificial containers and tree holes, but there are also thousands of other mosquitoes that occupy thousands of other habitats like salt marsh, or brackish water, or fresh water or polluted water,” she said. “They’re very successful creatures.”

And sometimes of course, too successful. Mosquito control is essential — not just because mosquitoes can really ruin your outdoor fun, but because of the disease-spreading aspect. Angelus said 2018 was an especially bad year for us humans, because there was a lot of rain that year and the year before.

“There was just mosquito habitat everywhere, and the populations were out of control.”

So much so that Angelus and her colleagues had to call in a helicopter to spray a field with a chemical that kills mosquito larvae.

“The farm field was underwater, and it was acres upon acres upon acres of floodwater,” she said, “but it was not deep enough where there was fish to eat the larvae, but it was just enough that there was just floodwater mosquito broods coming off one after another after another. The traps in the area were so inundated with mosquitoes. It was thousands upon thousands per night in that trap.”

Because of climate change, warm weather starts earlier in the year and lasts longer, so mosquito season has gotten longer and longer, Angelus said.

And there have been other challenges.

Since April, Autumn and her colleagues have been taking turns to work in the office because of the coronavirus outbreak, working from home every other week, to limit how many people are there at the same time.

She’s the only person who can identify the mosquitoes that get caught in the traps, but fortunately it is still early on in mosquito season so she’s not falling too far behind.

“New Jersey is going to be doing disease testing earlier this year for the first time, because with climate change, we’re finding that we have disease earlier and earlier. It’s going to be a change, and it’s going to be busy, but I’m excited to see what comes of it because I think that we are having disease circulation a lot earlier than anybody realizes, and that’s scary.”

“But it is always good to keep in mind that there is that good mosquito out there,” Angelus said. “They all are beautiful in their own way, but most of them are not good friends, just toxorhynchites.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.