To kick off Ramadan, Muslim astronomers rely on computer equations

While Islamic scholars track the moon in the night sky to mark the beginning of fasting, scientists turn to their computers.

Listen 4:36

Astrophysicist Nidhal Guessoum looking up at the night sky in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. (Courtesy of Younes Boudiaf)

For the world’s nearly 2 billion Muslims, major religious activities — like the month of fasting for Ramadan and the annual Hajj pilgrimage — correspond with the movements of the moon. Daily prayer is timed to the sun’s rise and fall in the sky.

“Islam wanted people to have some connection with not only God, but with the rest of creation,” says Muslim astrophysicist Nidhal Guessoum of the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates.

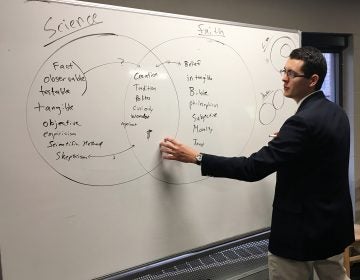

When it comes to daily prayers, astronomers and religious scholars are in agreement: Muslims keep calendars projecting prayer times for the entire year ahead. But, when it comes to determining the start of Ramadan and Hajj, there is a conflict of interpretation between astronomers and religious scholars.

Ramadan and Hajj begin when the crescent of the new moon can be seen in the night sky. According to a hadith, or a saying by the Prophet Muhammad, the instructions are to “fast when you see the crescent.” For religious scholars, this means they have to wait and see the crescent before announcing the start of Ramadan or Hajj. Often, this literally means a committee standing on a hilltop, waiting for a glimpse of the moon.

But sometimes the weather doesn’t cooperate, and one committee on its hilltop will see the crescent before another committee — on a different hill, or in a neighboring country.

“It creates disagreements and arguments, and people going, ‘the other mosque has decided to do this, but our mosque…’ and that lack of balance between the temporal affairs and the religious, spiritual affairs is really something significant to address,” Guessoum says.

Because of the varying proclamations about the start of Ramadan and Hajj, Muslims may only have a few hours notice before they begin fasting from food and drink.

For most people, modernity basically means that you can schedule everything in your life. In these two instances, you can’t.

In most Muslim countries, people have a whole week off for the Hajj holiday, but they can’t book a trip in advance because they don’t know which date the holiday will fall on. The whole night before the possible start of fasting or Hajj, people constantly refresh their cell phones, looking for an announcement.

But astronomers say that, actually, we should be able to plan ahead.

“It’s just equations! Just solve the equation, and put the time, t! I can tell you 200 years from now, what time people should be praying in Zimbabwe, for example. For the scientists, it’s like, it’s no big deal,” says Guessoum.

“And I say, if I bring the Prophet today, and show him all of my calculations, do you think he will say:, ‘Yeah, yeah, that’s really nice, but let’s wait until we see the crescent?’ He’s not going to say that! We know for certain from his life that he always promoted whatever is easiest on the people. And so now all we’re doing — we, the Muslim astronomers — is trying to find the optimal solution that still preserves the culture, but, at the same time, reconciles your spirituality and worldly affairs.”

Only Turkey, Albania, and Bosnia follow the astronomers and calculate the start dates of Ramadan and Hajj in advance. The rest of the Muslim world continues the debate.

Hebah Fisher is co-founder of Kerning Cultures, a podcast dissecting narratives of the Middle East through stories.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.