Churches introduce science education into Bible study

U.S. church congregations are shrinking, and members who leave often cite ‘science’ as one of the reasons. Some churches are engaging with science to stay relevant.

Listen 11:40

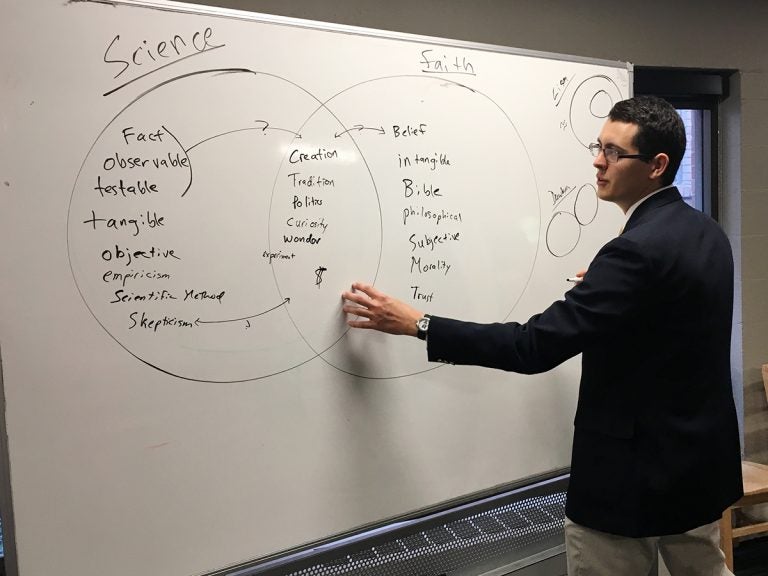

Matthew Groves, a divinity student, leads a Bible study class on science. Groves has made it his mission to educate faith communities on the ways science and religion can co-exist. (Natasha Senjanovic for WHYY)

On the first day of an adult Bible study course at Nashville First Baptist Church, guest teacher Matthew Groves invited his students to pray. “I pray we all be quick to listen, and slow to anger,” he intoned.

Groves grew up in a Christian household and today attends Vanderbilt University Divinity School. In college, though, he studied physics. He’s using his credentials in these two worlds to, he says, “bridge the gap between the scientific and the faith based communities.”

In his view, there’s a narrative of conflict between those groups. Elaine Howard Ecklund, a Rice University sociologist who studies how scientists and religious people perceive each other, says while both demographic groups are largely friendly to science and open to collaboration, there is conflict around certain issues. Both sides become upset when the other oversteps its bounds into the other’s territory. Groves doesn’t shy away from the contentious topics. His courses cover everything from evolution to climate change.

In Bible class, Groves drew a Venn diagram, two big circles with a lens of overlap in the middle, and asked the class to throw out words and concepts to fill it. One circle represented faith. The other science. The students threw out words for the Venn diagram. Under faith went Bible, subjective, and belief. They filed objective, observable and fact under science. Creation fit in the middle.

But there was some disagreement among the bible students about where things belonged.

“Everything you put under science has been under faith for me,” said Diana Chandler. “I would say my faith is based on facts, it is observable as I interact with God, and it is mostly testable.”

Groves drew arrows as a compromise before moving on.

After class, Chandler said she’s “careful and skeptical” about the class. “As a Christian, I don’t want anything to get in the way of my scripture,” she said. She staked out a role for herself in the class: “I just want to make sure that I’m here to guard the faith, to proclaim the faith, to speak up for Jesus and to defend the faith if it is challenged.”

Others are more open. Carol Butler said she’s glad to have Groves guest teach. “We don’t understand all the mysteries of science, we don’t know all the mysteries of creation, but we know that they’re one and together,” Butler said.

Groves says he’s satisfied if just a couple of people in any given class leave with a better understanding of scientific concepts and clearer ideas on how to accommodate them into their faith.

Religious institutions in the United States are losing members, even in the South, the nation’s most religious region. Those who leave often cite ‘science’ specifically as one reason. Groves says for churches to not only survive, but to be relevant institutions, they have to engage with the things people are struggling with today.

“Climate change is a substantive issue. Artificial intelligence. Bioethics. A lot of big issues humanity is going to face in the next hundred years are focused on science and technology. And if the church wants to be a part of shaping the direction humanity takes, the church needs to have a seat at the table and you can’t have a seat at the table if you don’t speak science.”

Groves is not alone in his thinking. A small movement of pastors, churches and seminaries are introducing different versions of science education to their services and curriculums.

“I think faith can give us purpose and hope and how we see the world and how we treat our neighbor. And science can help us understand the mysteries of the universe and how our world operates,” said Pastor Will Rose, who has introduced science programming to his congregation in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Working together they can help unravel questions people have about our complex world, he says. “The challenge comes when we’re set in our ways and how we interpret Scripture.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.