Sacred tobacco and American Indians, tradition and conflict

American Indians have the highest smoking rates in the country: US commercialization of tobacco continues to complicate sacred use of the plant.

Listen 12:10

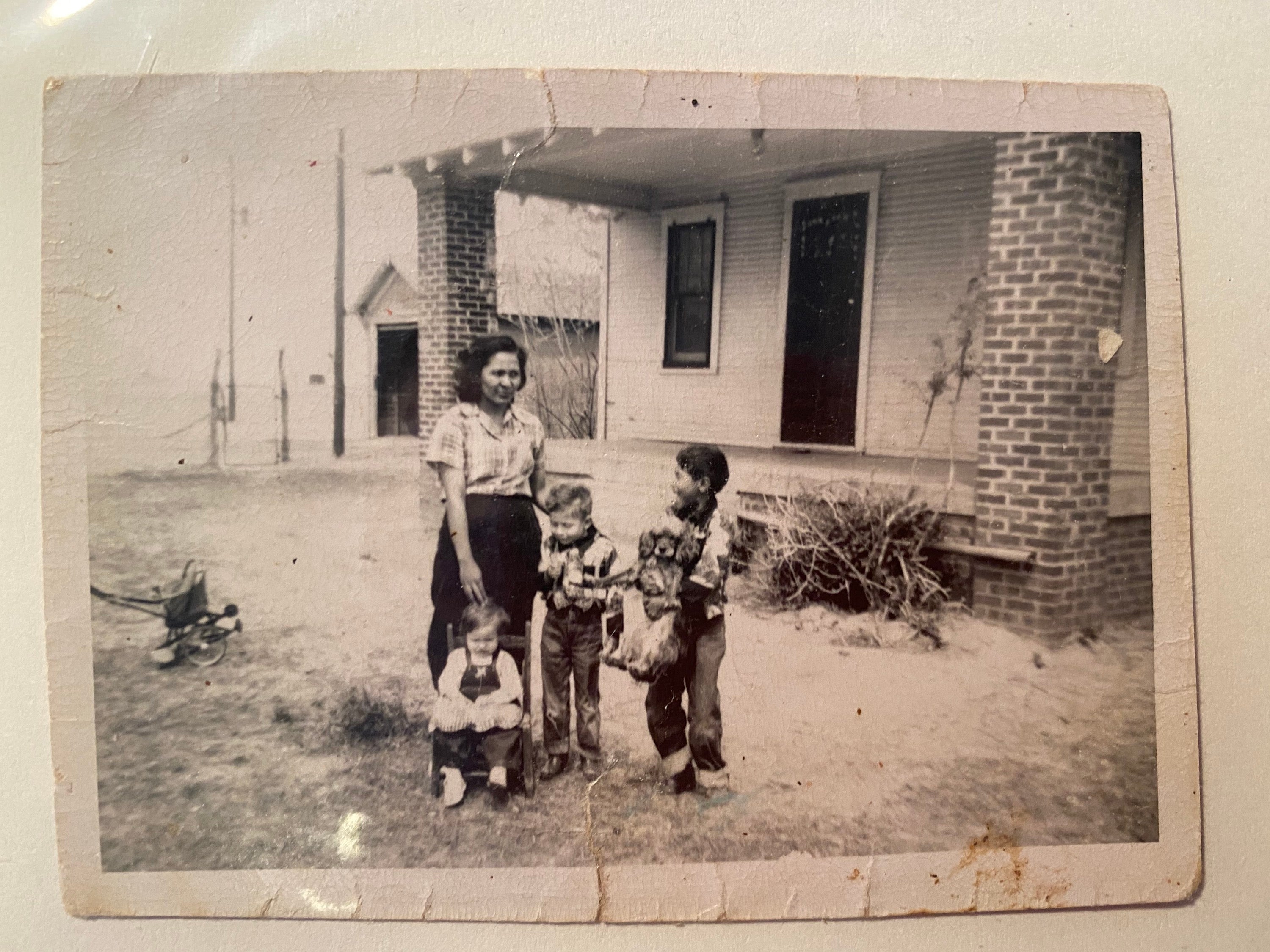

Sean Brown (Seminole Nation of Oklahoma) as an infant with his great-grandmother, Mable Brown (Mama-on), who would tell him countless stories about the people he came from. (Photo courtesy of Sean Brown)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

Sean Brown grew up on an American Indian reservation in Seminole County, Oklahoma where he says tobacco was everywhere — in TV and radio ads, on billboards and storefronts.

“Everyone in my dad’s family smoked,” Brown said. “Chain-smoked a pack a day — grandma, grandpa, aunts, uncles, cousins, dad, all of them.”

And at 9 years old, Brown had his first cigarette. He took it from one of his mother’s packs.

“Mom didn’t even notice because she worked 16-hour days,” Brown recalls. “She wasn’t counting how many smokes there were in there. Me and my friend, we chain-smoked about 10 straight.”

But for Brown and many American Indians, there’s another side to tobacco.

As a kid, Brown split his time between Seminole County and the family homestead in Sasakwa, Oklahoma, where his great-grandmother, a traditional medicine woman, would burn tobacco in the house.

“Mama-on, my great grandmother, she used to heal people,” Brown said.

“And I was just a little tot, you know, threes, fours and fives. But I remember very vividly of people coming from all over just for her to put her hands on them. The smell of herbs in the kitchen. You can’t beat it.”

What’s sacred tobacco?

Mama-on was burning sacred tobacco — not the commercial tobacco that’s in cigarettes.

Sacred tobacco, which Brown calls “little tobacco,” is a smaller plant (Nicotiana rustica) that grew in different varieties across North America before European contact. It’s stronger and harder to inhale, which means that it wasn’t smoked as frequently. And it’s a lot harder to come by these days.

“Little tobacco is so much more powerful,” Brown said. “It looks kind of like basil. It can grow in harsher conditions, and it doesn’t have as many viruses or bacterias that attack the plant, so you can use it as a pesticide.”

Among the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, Brown says, “little tobacco” is considered a sacred medicine. It’s commonly used for prayer or spiritual protection, or gifted to someone to express thanks.

Centuries of European encroachment on American Indian land has made it hard to grow and access the plant in its original form. But Brown says the story of tobacco is part of a larger history of who he comes from.

“I am of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, Alligator Clan, Tvsekiyv Harjo Band, which is descended from the Okone Band,” Brown said. “[They were] the very first people to break away from the Creek Muscogee and leave and go to Spanish Florida and become the Seminoles.”

At the beginning of the 1830s, more than 125,000 American Indians lived on millions of acres of land in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, and Florida – land their ancestors had occupied and cultivated for generations.

But the federal government, working on behalf of white settlers who wanted the land to grow cotton and tobacco, forced American Indians to leave and relocate to designated “Indian” territories across the Mississippi River — a journey infamously known as the Trail of Tears.

“And you had to walk two thousand miles through it barefoot,” Brown said. “Little food, little blankets, little anything, and then in the meantime, you’re put in corral pens like stockade.”

At the same time, European settlers had already begun growing a different variety of the tobacco plant, Nicotiana tabacum, which was easier to inhale, and therefore more likely to cause addiction.

As land was taken and warfare erupted between American Indians and settlers, tobacco took on a new purpose.

According to the late medical historian, Stephen J. Kunitz, the calumet (pipe) ceremony was common during the pre-contact period and throughout the 17th and 18th centuries on the Northern and Southern plains, the prairies and the east.

“However, at the prairie-plains margin it spread and became pervasive in the early historical period due to the conditions of population dislocation and migration,” wrote Kunitz. “These conditions were caused by Europeans pushing westward, by the attraction of buffalo on the plains, and by the impact on the Plains tribes of acquiring horses.

The result during the 18th and 19th centuries was intertribal warfare and the disruption of tribal relationships all across the Northern Plains, as well as across the Great Plains more generally.”

In the advent of American Indian dislocation, historians say tobacco became more thoroughly integrated into social relationships between settlers and tribes — but, Brown says, not in the way you might have heard about it in movies, what Hollywood Westerns called “the peace pipe.”

“It has nothing to do with peace whatsoever,” Brown said. “It’s just what those guys called it when we brought out the pipe as a deal sealer. When you share the pipe, that solidifies the bond between the two people and the words are solidified within the smoke. And so that smoke rises to our ancestors, which then solidifies it in the depths of time.”

‘A chokehold on an entire culture’

By the time many of the Seminole people were forcibly relocated to Oklahoma, they were thousands of miles away from their local plants and medicines. Brown says they had to relearn where to find and cultivate these sacred plants.

But by the end of the century, commercial tobacco production really took off — coming close to eradicating native varieties altogether. That’s meant many tribes have had to replace sacred tobacco with the commercial variety, blurring the lines between what’s spiritual and what’s not. That line was especially blurry for Brown as a young kid.

“‘You’re an Indian, so you need to smoke tobacco,’” Brown said. “Nobody really said that, but that’s kind of the impression [I got] that because it is sacred, we have to now use commercial tobacco to still maintain sacredness … Wow, talk about putting a chokehold on an entire culture.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

Dana Carroll is a professor of environmental sciences at the University of Minnesota. She studies commercial tobacco use and its health outcomes.

“There’s evidence that the tobacco industry has specifically targeted this population … by using Native Americans on cigarette packs,” Carroll said.

“There’s a well-known one, American Spirits, [which] portrays an [American] Indian chief using traditional tobacco. And you can imagine it blurs the line, especially for youth: Is that commercial tobacco? Is that really bad or is that OK?”

Experts say American Indians have been the target of aggressive marketing by cigarette manufacturers since at least the 20th century. In 2020, Carroll and a team of researchers analyzed data on American Indians’ self-reported exposure to tobacco ads from stores, tobacco package displays, direct mail, and email marketing.

They found that exposure to retail and email ads for tobacco products was higher among Americans Indians and Alaska Natives than their white American counterparts.

“Email really goes behind the eyes of the public to the individual,” Carroll said. “So it circumvents Tribal leadership and gets to their Tribal members.”

American Indians have the highest smoking rates in the U.S.

High smoking rates have had a devastating impact on American Indians, especially those in the Northern Plains region. Of all racial/ethnic groups, American Indian adults have the highest smoking rate in the U.S. and are almost twice as likely as white Americans to die from lung cancer.

“But we also see that disparity across many different diseases,” said Madison Anderson, an Anishinaabe doctoral student in epidemiology at the University of Minnesota who studies cardiovascular disease and tobacco use in American Indian communities.

“So we see that with cardiovascular disease,” Anderson said. “We see it with lung cancer. We see it with throat cancer.”

She says one of the biggest issues has been that national health surveys under-sample American Indians, which means there aren’t great region-specific metrics for smoking use across the more than 576 federally-recognized tribes that exist.

For example, there are great differences in smoking- and tobacco-related mortality between American Indians in the Northern Plains and those in the Southwest. According to a 2009 study led by leading Diné tobacco control expert, Patricia Nez Henderson, cigarette smoking initiation was much higher among the American Indians in the Northern Plains (47%) than among those in the Southwest Indians (28%).

Furthermore, there’s great variety in how different tribes relate culturally and secularly to sacred and commercial tobacco. But Anderson says a lot of smoking cessation programs don’t take into account the sacred role of tobacco in American Indian culture, and don’t differentiate between “little tobacco” and the commercial kind, so the message to quit falls flat.

“A lot of anti-tobacco messaging can be taken in a negative way,” Anderson said. “If you do not distinguish the difference between commercial and traditional tobacco, telling someone to live a tobacco free life doesn’t necessarily give off the same message.”

Sean Brown experienced that disconnect in 2015 when he first tried to quit smoking. At that point he had moved to Montana and saw an ad on TV for the state’s quitline.

“I gave them a call, nice people, but I had a problem initially with just giving up tobacco,” Brown said. “I couldn’t in my soul just give it up.”

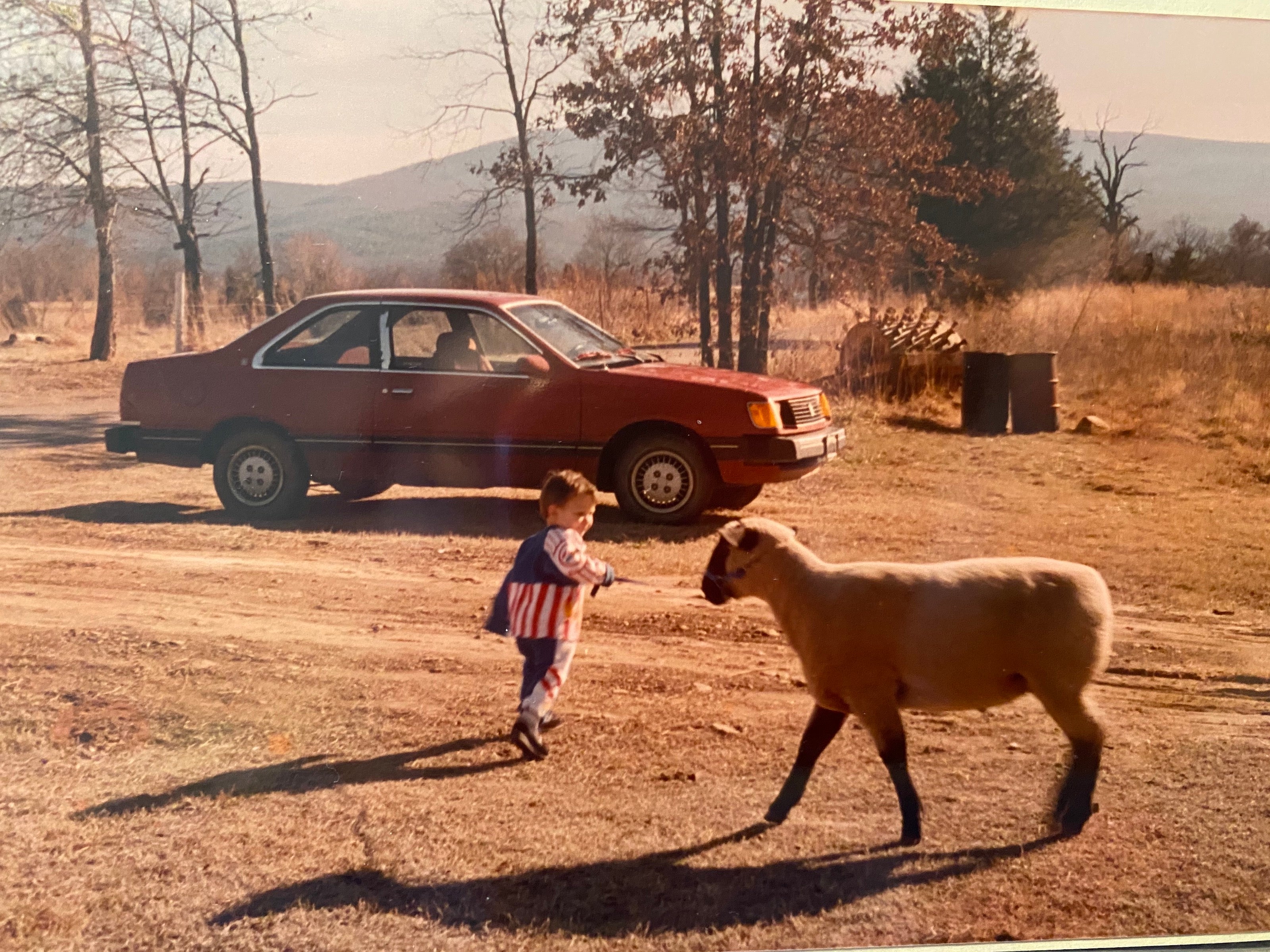

By then, Brown had been using commercial tobacco consistently for at least ten years, smoking a pack a day by the time he was in his early twenties. Years of smoking took a toll on his body — he had trouble just taking a walk or playing with his son at the playground.

Then, in 2020, his teeth started to feel weird. So he went to get them checked out by a dentist.

“And apparently I was somewhere in a mid-stage of this progressive gum disease,” Brown said.

That’s bad news for your teeth and oral health. But it also can damage blood vessels in the heart and brain over a long period of time. For Brown, this was his breaking point. He knew he had to quit, but he didn’t know how he was going to do it.

A culturally specific program

Luckily, the Montana quitline he’d tried to use five years earlier now offered a culturally specific program just for American Indians called the American Indian Commercial Tobacco Program.

Thomas Ylioja is the clinical director for health initiatives at National Jewish Health, which operates telephone helplines in 20 states across the country for people trying to quit tobacco. He says their usual approach of telephone coaching sessions didn’t seem to work for their American Indian clients.

“When they would call in, [they] were less likely to go from completing an intake on to completing a coaching call,” Ylioja said.

“If they did complete a coaching call, they were less likely to go on to complete a second or a third coaching call, which is where we start to see quit rates really start to increase, after about that third coaching call.”

A lot rides on that first call, which is why Ylioja says his team had to completely revamp the intake process altogether.

“So instead of it being a series of questions which can seem culturally inappropriate for some American Indian communities,” Ylioja said, “The intake has been adapted to have a more conversational flow, asking permission to continue asking questions instead of just sort of hitting them with a barrage of questions right from the beginning.”

After several conversations with indigenous leaders in Montana, Ylioja says it was clear that American Indians wanted to work with people from their own community who could understand the cultural significance of sacred tobacco in their lives. So the quitline exclusively hired American Indian coaches to work with participants.

And it worked. People stayed in the program longer.

Research shows that American Indians’ rates of quitting using culturally-tailored programs are about the same as non-American Indians in standard care programs, Ylioja says.

“What we see is that culturally tailored programs increase what we call the acceptability of the program,” Ylioja says. “What that means, is that people are more likely to engage with it.”

So without the culturally-adapted programs, specific racial and ethnic groups like American Indians with great health disparities would be less likely to stick to the standard care program that seems to work for most of the general population.

The first time Brown called Montana’s culturally-specific quitline, he was matched with a coach named Kim. He vividly remembers a sense of relief washing over him when he heard her voice.

“There’s a certain dialect that comes from natives that you just pick up,” Brown said. “And it’s just something about it, it makes me feel more at home.”

Kim asked Brown about his current tobacco use, and what his cravings were like. And then, for the next couple of months, Kim would call him for 15 minutes every week to check in.

“It [was] nice to have somebody to just call in [and say], ‘Hey, Sean, how are you doing today? How are you feeling? Do you have enough of the lozenges or the gum or the patches or whatever?’” Brown said.

By Brown’s 50th day in the program, he was past most of the serious urges and withdrawal symptoms, and was no longer depending as much on the nicotine supplements.

Ultimately, he says, Kim saved his life.

Brown hasn’t used commercial tobacco since the program ended. The pain in his teeth has subsided. His blood pressure is normal again. And he’s not as anxious and high-strung.

“It felt like … a breath of fresh air, like freedom,” Brown said.

Brown says across many American Indian cultures, there’s this concept that every individual is a culmination of the previous seven generations.

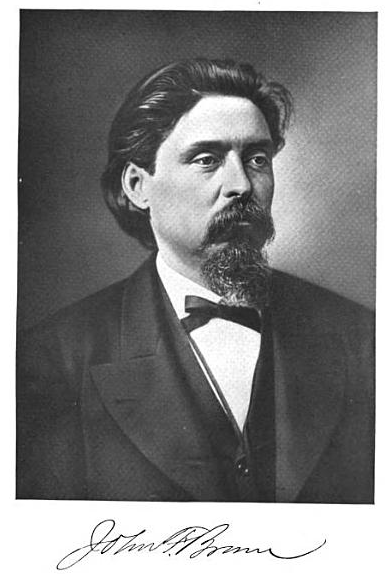

He feels a strong connection to his ancestor, John Brown, the last governor of Seminole Nation before Oklahoma statehood. He founded Brown’s hometown of Sasakwa, Oklahoma in the late 1800s and negotiated a series of agreements and treaties between American Indian tribes and the federal government.

“I have his Bible,” Brown said. “It is a New Testament copy entirely of Muscogee. It was printed in 1905, and it has his writing in it. And all of us have put our hands upon it because he led us through Oklahoma Times. And now it’s Montana Times. And Montana Seminoles are, ‘by God — we’re not going to be held down by commercial tobacco.’”

Support for WHYY’s coverage on health equity issues comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.