For some graduate students, the cost of doing science is their mental health

Years of research, classwork, teaching and study can take a stressful toll in almost any area.

Listen 12:21

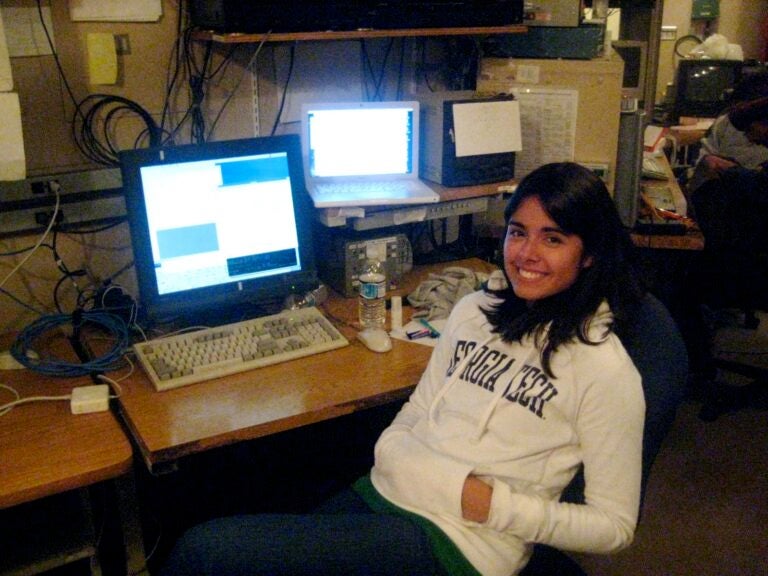

Nicole Cabrera Salazar at the University of Hawaii 2.2-meter telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii in 2008. (Courtesy of Nicole Cabrera Salazar)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

In 2012, Nicole Cabrera Salazar was studying for an exam that was going to decide her immediate future.

It was her qualifying exam for a Ph.D. in astronomy at Georgia State University: a six-hour written exam, then an oral exam in front of a panel of professors. Passing meant moving on with the degree. Failing meant one more chance before she had to leave the program.

In the months leading up to her exam, her entire life consisted of research, classwork, teaching classes and studying.

“When I was studying for it, I started noticing that my handwriting had changed,” she said. “It was a lot more messy … I used to have really neat handwriting, and I could no longer write in a straight line, and after just a few minutes of writing, my hand would cramp up really painfully … It’s like I almost forgot how to hold a pen in my hand.”

She went to doctors, got an MRI, even went to a neurologist. They said it was just stress. She started going to therapy.

This is widespread in graduate school. A survey from two years ago found that almost 40% of graduate students showed signs of anxiety and depression, much higher than in the general population.

In Salazar’s fourth year, she wondered if research was something she still wanted to do.

“I started to really hate my research, and even though it was … really my dream to become an astrophysics professor and I was really committed to the career path and everything, it came to a point where … it was not bearable anymore.”

She told her adviser about her doubts.

“And my adviser said, ‘Oh, you know, I’m not surprised because I don’t see that you have a passion for astronomy.’ And I was like, ‘What do you mean?’ And he was like, ‘Well, you put more passion into your baking than you do your astronomy.’”

Baking was a creative outlet for Salazar. She would make cakes for people in her department who had birthdays.

“I didn’t know what I could do because … my entire life had been planned around becoming an astronomy professor,” she said. “In the end, I did decide to finish my Ph.D., if nothing else maybe because I’m a really stubborn person.”

But the stress kept building. She took four months of medical leave.

“I was so depressed that … I couldn’t leave my bed, every single task felt impossible, it felt like an insurmountable thing to get up and get dressed or take a shower.”

She saw a psychiatrist, got on medication that worked, then returned to research.

“It was really hard to come back to school because … all the negative experiences I had, my brain associated that with my office, with my desk, with my research,” she said. “In the end, I just ended up taking all my stuff home with me, and I wrote my entire dissertation from home, and that was really isolating, too, because it took 10 months, and I was just alone.”

She did graduate with her Ph.D. And she wondered: Did it really have to be like that?

“It’s like you’re trying to walk through a door frame, but you don’t fit through it because it has a very specific shape, and so in order to walk through, you have to cut away parts of yourself.”

In interviews for this story, many scientists — from different backgrounds, in different stages of their academic careers, working in a variety of disciplines — echoed in their way what Salazar went through, even if they didn’t experience all of it.

Subscribe to The Pulse

Ecologist Jasmine Childress said a common idea is that “science is science and we don’t need to take into account our personal identities.”

“I don’t think that can be farther from the truth,” Childress added. She is in the sixth year of her Ph.D. program at the University of California Santa Barbara.

It seems as if the philosophy that science is based on observable facts also sometimes leads to a lack of understanding that science is done by humans, not robots that do experiments, so those people need support.

Childress is biracial: Her mother is white; her father is Black. And she and some fellow students of color wanted to improve the work environment.

“A couple of years ago, myself and two other graduate students of color decided that we wanted to start a diversity equity, inclusion and wellness committee in our department that … looked at different demographics of folks … as well as their wellness, be it physical or mental wellness,” she said. “When we took it to the department, they told us, ‘No we don’t need that.’ The one person who we thought would be the best to … introduce this idea said, ‘If I spent any of my time talking or thinking about DEI [Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion] issues, I would get no science done, that’s not my job.’”

Relieving some stress points

Part of the problem is culture. Graduate students in science go to class, but they also teach and do research. When they graduate, they often depend on letters of recommendation from their advisers if they want to get anywhere in their field. If that same person asks them to spend long hours and weekends in the lab, it’s hard to say no.

There is no HR department. The researchers who teach young scientists and run labs get their jobs mostly based on their success in science. They don’t get funding or major awards for being good mentors.

But scientists are talking about the lack of support and the stress of graduate school more openly now.

Russel White was Nicole Cabrera Salazar’s Ph.D. adviser. He’s a professor of astronomy and now also is the director of graduate studies for the astronomy department at Georgia State University.

First of all, White said, his department has changed the qualifying exam, the one that was so stressful Salazar noticed her handwriting change.

“Her experience was probably like the experiences of many students in the program,” he said. “Going through the qualifying exam is definitely one of the more stressful moments.”

It’s no longer a six-hour written exam, White said. Now, it’s about writing a research report and presenting their work like they would at a scientific conference.

“It’s in some sense encouraging them to get started with research early, and if that’s what we’re really training them to do, why not test them during the qualifying exam?” he said.

The idea is that learning those skills is more productive than having the students take a long exam on material they have already proved they know.

He said he also recognizes that it’s important for students to feel comfortable talking about what they’re going through. Their department is doing a survey to see how students feel about mental health resources, how inclusive the department is, and what can be improved. A student suggested that idea, based on similar work at the University of California Berkeley.

Schools overall are more open when it comes to talking about mental health, said Jen Heemstra, an associate professor of chemistry at Emory University.

“It started by just saying a few words at the start of a group meeting to remind people that your health, your emotional, physical, mental health and well-being, are the most important thing here, and we’re here to do research but none of that matters if you don’t finish your career as a healthy individual.”

That is a part of her lab policy manual now, along with sections on taking time off for health concerns, personal emergencies and work life balance. It’s an open document, and other labs have adopted similar policies.

Students are pushing for change, as well. Graduate students at universities have organized in recent years. Some have formed unions.

Nicole Cabrera Salazar ended up not becoming a professor of astrophysics after getting her Ph.D. Now, she spends her time helping students who are going through what she went through — she started a consulting company to make scientific workplaces better for people in marginalized groups.

“Every place that I visited … I have students coming up to me and telling me their stories, and telling me about people who didn’t make it, and who left. There is no institutional memory of them ever being there … the department just gets to continue as it always has, but the people who leave, their lives are completely impacted, they are completely changed by these experiences.”

“I like to think about it more in terms of, like, what those people have lost, not just their time, but their hopes and their dreams.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.