Following a stroke, finding the words can be a lifelong endeavor

Science owes a lot to aphasia and what it reveals about how language works. But many worry it has been widely misunderstood, leading to missed recovery opportunities.

Listen 11:58

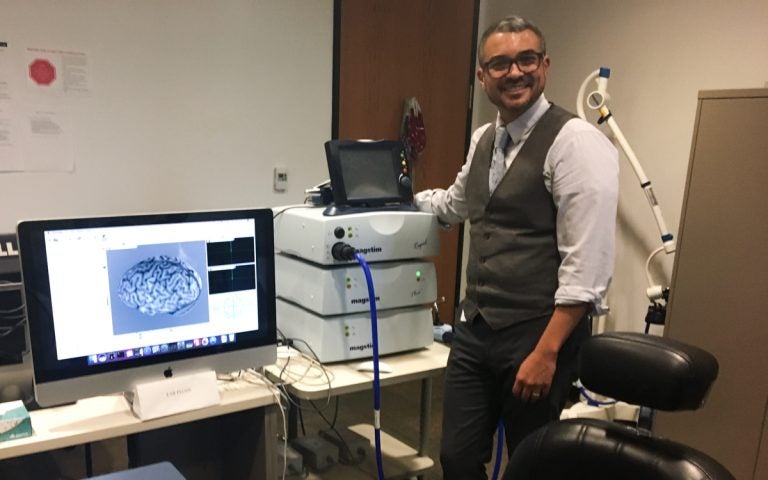

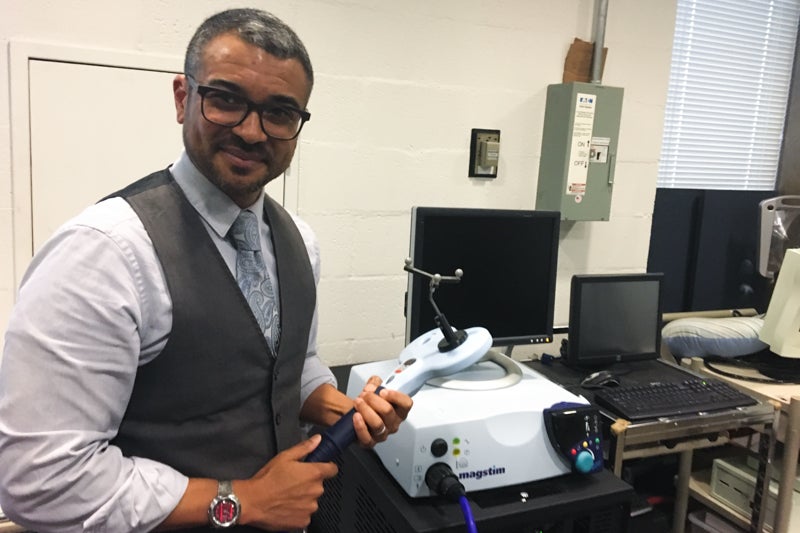

Roy Hamilton runs the laboratory for cognition and neural stimulation at the University of Pennsylvania. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

As Michael McHale searches for the words, he closes his eyes to concentrate and process.

“I know what I want to say, but it doesn’t come out clearly,” McHale said, in between deep pauses and breaths. “I’m sorry, but I hear everything. I know everything that’s going on around me, but I just can’t respond to things as quickly I used to.”

McHale, 51, had a stroke nearly two years ago. The blood clot in his brain affected an area responsible for language production and processing, inhibiting his ability to communicate clearly.

“It’s a tough thing,” he said. “I started out with one word per day.”

McHale has aphasia, usually caused by a trauma in the brain. Experts worry the condition has been so widely misunderstood, that it’s leading to missed rehabilitation opportunities and intense isolation for many of the estimated two million or more people nationwide who develop it. And yet, science owes a lot to this condition, to what it has revealed about how language and even the brain itself works.

What aphasia is and what it isn’t

Aphasia can manifest differently for different people, depending on the type of trauma to the brain. It can cause difficulties in reading, writing, speaking and comprehension. For some, retrieving certain types of words are a challenge. For others, numbers get all mixed up.

“The way we evaluate it is we look at four language modalities: auditory comprehension, speech production and speech output, reading comprehension and written language skills,” said Karen Cohen, a speech language pathologist at Moss Rehab’s Aphasia Center, one of the oldest aphasia centers in the country.

But Cohen says there is one thing aphasia does not affect.

“It affects language processing, it does not affect intelligence,” she said. “It’s really important because when people with aphasia talk, other people think they’re stupid, and that can be the perception.”

Some liken the experience of having aphasia to being in another country, where the language is totally different. You’re completely present. You may have even studied the language. You can take in what’s going on around you, and you know what you want to say. But the words — the numbers and even phrases — aren’t quite there, though they may be right at the tip of your tongue.

Cohen runs weekly “conversation cafes” and other support groups at the rehab center. She sits at the head of a long, rectangular table in a bright room. McHale and a handful of others regularly attend.

“I realize that I know what I want to say, I know it inside and I can’t,” a woman seated to the left of Cohen shares, pausing. “And, my husband is annoyed.”

Her situation, where a spouse or friend or caregiver gets aggravated, is really common, according to Cohen. That’s why the focus here is on building social connections, confidence and communication strategies for when those words just won’t come, or when they’re all jumbled up.

“I’m a retired microbiologist,” said Richard Berman, who’s seated next to the woman.

Berman, 74, had a stroke six years ago, and has since struggled to say that word – ‘microbiologist’ – his lifelong profession. Here, everyone encourages him to keep trying, to keep practicing, with the help of some lighthearted teasing.

“We like to make him say it as much as we can,” Cohen said, as everyone chuckles. “Because of the way speech was affected for his stroke, somebody else can say it and not have any trouble with it. The strategy he actually uses is to say it one syllable at a time, and it comes out perfectly.”

Berman recites ‘microbiologist’ again, hitting every syllable, perfectly.

It’s met with cheers and laughter.

The conversation group is part of a growing shift in how aphasia is treated, taking what’s called a “life participation approach.” It’s used in addition to one-on-one therapy, and perhaps most importantly, it’s intended to continue for a very long time. That’s because what scientists now understand about how the brain repairs itself and how long it takes is changing.

Aphasia as a window into the brain

The ability to communicate is so inherent in day-to-day functioning that it can easily be taken for granted. And yet aphasia — and what happens when language abilities are damaged — has helped shape our entire understanding of how language and the complex systems that exist behind it work.

“Aphasia in the setting of stroke is actually one of the most important disorders in the history of neurology for establishing the idea that there is a relationship between different regions of the brain, different centers and cognitive ability,” said Roy Hamilton.

Hamilton runs the Laboratory for Cognition and Neural Stimulation at the University of Pennsylvania, where he spends his days using the advances of modern imaging technology and neurostimulation techniques to research the brains of of health people and people with chronic strokes. He’s looking into the brain itself, for clues about language, in hopes of developing better ways to repair those functions when they’re damaged.

One of the cases, he says, that really shook the medical field was a patient known as ‘Tan’ from the mid 1800s.

“And the reason he was referred to as Tan was because after he had his lesion in his brain, that was the sound that he primarily generated. Instead of coherent speech, just ‘Tan.’ ‘Tan’, ” Hamilton said. “You would ask him questions, he would try to answer effortfully, frustratingly, and that’s what he would produce: tan.”

The famed neurologist Pierre Paul Broca studied Tan, and then his brain once he died. He observed that the left frontal area was the damaged part. What that told him was that for most people, language is localized in the brain, in the front, left hemisphere. There’s an area of the brain that even bears Broca’s name.

“And we now often refer to patients who have this problem that predominantly involves the production of language as having a Broca’s type aphasia,” Hamilton said.

Modern imaging points to even more complexities

This idea that certain parts of the brain are responsible for specific functions was big at that time, and it continues to this day. Another way to look look at it: damage to one part of the brain that’s responsible for a certain function, like language, will then result in damage to those language abilities.

There is actually way more to this. A pediatric patient of Thomas Barlow’s in 1877 foreshadowed the complexities, Hamilton says, because even when part of the brain that’s responsible for language is damaged, the brain can still recover language function. Other areas of the brain may work to compensate, finding alternate paths. Scientists have also since learned that language function is not entirely siloed in just one part of the brain.

“One of the big things that we now understand to be different is that the brain is not static in its function,” he said.

The brain has a plasticity — or, neuroplasticity — to it. Hamilton and others are trying to better observe these dynamics and incredibly complex systems with advanced imaging, like FMRIs, and other neurostimulation techniques. He has studied dozens of people who’ve had strokes, whose brains — months and years later — have found alternate pathways for language. Hamilton is trying to observe the brain activity that lights up in certain parts of the right side of the brain, for example, when these patients undergo language tasks.

He hopes to take what he learns from that research a step further.

A centerpiece of his lab is an electromagnetic stimulation machine.

It’s about the size of a VCR and has a blueish hose coming out of it. The multi pronged antenna on the end allows a camera to identify where the hose and coils are in space. When he fires it up, the passing of current jostles the wire inside the coil, inside that hose, producing an electromagnet that then creates a popping or tapping sound.

“There’s a flux of the wire, and in that moment, the wires scrape against each other. That’s what you’re hearing,” Hamilton said. “We can focally choose an area of the brain and deliver pulses of a fluxing magnetic field that then generates current in the brain areas and causes brain cells there to fire.”

When those magnetic pulses are directed in a certain targeted way on one’s head, the idea is it could activate (or inhibit) specific areas of the brain and its related functions. As a popular demo, Hamilton sends pulses to the brain’s motor cortex, and specifically that part that sends signals down the spinal cord to the hand. When stimulated with magnetic pulses, Hamilton can get a person’s hand to flinch.

Transcranial Magnetic Therapy is approved by the FDA as a targeted treatment for depression. He wants to figure out how to use such an approach to help stimulate and activate language recovery. To do that, though, he’ll need to figure out a lot of unknowns, such as what exactly are the properties of how the brain decides which alternate pathways to take, and then how effective those pathways really are.

These are all things that the field of neuroscience continues to explore and debate.

A longterm rehabilitation path

For people with aphasia, like those who wind up at Moss Rehab, there’s a more urgent question: how much time does the brain have to repair itself?

Hamilton says the traditional thinking has been that a person mostly plateaus after about six months.

Therapy is critical during that time, but “there is more evidence to suggest that, in general, this arc of recovery is likely much longer than we think it is.”

As for how long?

“I do not have an endpoint in mind. I think that the evidence suggests that that is not bounded by some concrete timeframe,” said Hamilton.

In other words, the brain continues to repair and recover language over time.

“I think speech language pathologists have always known that,” said Sharon Antonucci, director of Moss Rehab’s aphasia center. “While there are no guarantees about where you will end up in your recovery, opportunities for rehabilitation and opportunities for improving and increasing communication skills are lifelong.”

Antonucci says doctors are still trying to figure out the best level of intensity of therapy immediately following a trauma to the brain, like a stroke, in order to strike the right balance between allowing the brain to both heal and regain its function. But she worries that after that period of six months, people may stop getting therapy, and even worse, give up altogether because what they’re often hearing from their doctor is that they won’t get any better after that.

“This is something that we hear from people with aphasia over and over and over again,” Antonucci said. “That message seems to be fairly pervasive, and I think it’s a message that is created due to lack of education and lack of experience.”

She says the implications of this can be devastating. Social interaction is a critical part of the rehabilitation process. Yet losing that ability to communicate is incredibly isolating, further compounding the situation.

“A piece of data that is going to be coming out soon suggests that 20 percent of people who are six months after stroke with aphasia report having no friends,” she said.

Finding the words, finally.

A few doors down from Sharon Antonucci’s office, that conversation cafe moves into a mid-day book club.

“If you look down somewhere around 10 lines, it says ‘Jones was an indispensable and mysterious’ – everyone have it?” Cohen says to the group, referencing an excerpt from the book.

The group is discussing “Manhunt, the 12 Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer” by James Swanson.

“It’s unbelievable like how far I’ve come,” said Michael McHale, who now volunteers with stroke patients at a nearby hospital. Manhunt marks the third book he’s gotten through since his own stroke.

Cohen has prepared a special worksheet to help people who have challenges in reading comprehension follow along. It includes a list of the names of every person who appears in the reading, an explanation of who they are and a brief summary of events.

“I think it’s worth reading this part aloud, about what Jones did. Someone want to read that?,” she asks.

Charlie Salber begins reciting the passage aloud. He’s 70 and had a stroke three years ago (as a result of his aphasia, he started to say it was in the year 2017, even though he was thinking of the right year, 2014. He caught himself and corrected it).

Initially, Salber says his daughters had to really push him to attend the group because he was afraid to go out and not being able to speak well around others. Had he not come, he says he’d probably still be staying inside his house most of the time.

“I don’t think my speech would be as good as it is right now, and I’d be sitting at home just wondering what to do,” he said.

Twenty years ago, this aphasia center might have been one of just a small handful nationwide. Now there are about twenty in North America, according to Antonucci. For Charlie and several others who attend the group, they say spaces like this, that encourage social interactions, are a lifeline. For one, it enables them to do something that is really hard to do outside, and as a result can be a major barrier to engaging with the world. Here, they can finally complete their sentences, no matter how long that might take.

“It may sound strange to you, but it’s important that people understand that people with aphasia need time to finish their sentences. Don’t interrupt them. That’s the probably worse thing you can do, because it’s very, not only demeaning, but it’s — what’s the word i’m looking for — ”

Salber pauses for moment, until he finds it. Then with a firm voice, he completes his thought.

“Destructive to their confidence.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.