What happened to the quest for a universal language?

A century ago, Esperanto seemed poised to solve the problem of "scientific Babel."

Listen 4:02

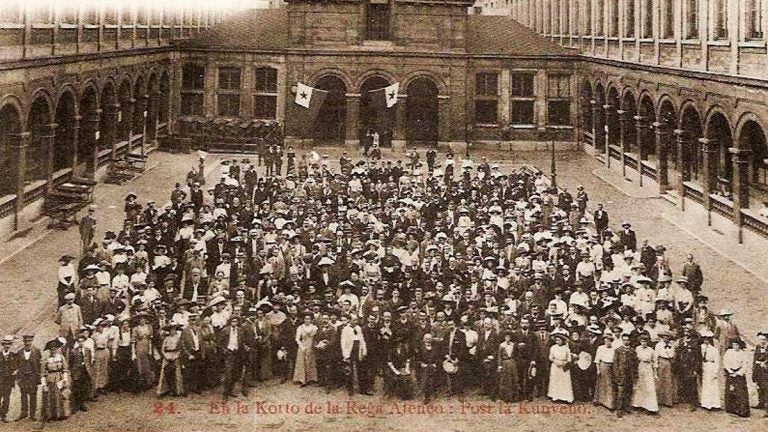

A photo from an Eperanto conference in Belgium in 1911. (Wikimedia Commons)

Chances are, you’ve never heard of Volapük. Gloro and Novial probably don’t ring any bells either. If you know of any constructed language, there’s a good chance it’s Esperanto.

At the very least, this “universal” language — created to be a neutral means of international communication — might sound familiar.

“Many of the words sound a bit comical to English speakers,” says Michael Gordin, a professor at Princeton University who specializes in the history of modern science. “The word for ‘bird’ in Esperanto is ‘birdo.’”

Gordin says scientists were some of the most enthusiastic supporters of goofy-sounding constructed languages when dozens of them began to be invented in the late 1800s.

Science was booming, and if you wanted to keep up, you had to know a lot of different languages. Today, English is the lingua franca of scientific research. Back then, it shared dominance in the field with two other languages: French and German.

But soon that started to change.

“Starting around the 1860s and ’70s, you get expansion of railroad networks, you get expansion of telegraph networks, people travel more easily,” Gordin says.

As the world became more interconnected, the language barriers between scientists traveling around Europe became harder to ignore. And discoveries were starting to be published in even more languages, such as Japanese and Russian.

Gordin says scientists worried they were heading toward a Tower of Babel scenario, where advances were being made but nobody could understand each other.

So some of them decided to take on a quest to find a new invention that could serve as the universal language of science.

Esperanto was one of the most popular of these constructed languages. A Polish ophthalmologist, L.L. Zamenhof, invented it and published the first primer in 1887. He designed Esperanto to be very easy to learn. The vocabulary draws on familiar root words from European languages, and its pronunciation and grammar consistently follow the same rules.

“It sounds vaguely like Portuguese,” Gordin says.

In 1907, Esperanto was the frontrunner when an international delegation of scientists met in Paris to decide which one of the constructed languages would become the new official language of science. But for some of the delegates, it wasn’t up to their rigorous scientific standards.

“Esperanto is a pretty good language, but it has some quirks and weirdnesses and flaws and people quibble about it, so they want to create a new language that’s going to be absolutely perfect,” Gordin says.

In the end, they voted for a reformed version of Esperanto called Ido.

But Esperanto speakers were stubborn. Despite the vote, most of them remained loyal to Esperanto and refused to take up Ido. That created a schism, which didn’t bode well for the adoption of an international language of science.

“The perfect is the enemy of the good,” Gordin says.

But in the end, it was World War I that spelled doom for the project.

“The war ruptures internationalist instincts as people devolve into nationalism and fight,” Gordin says.

After the war, the quest to find an ideal constructed language lost steam. Gordin says World War I also started a shift toward English as the dominant international language of science. There were efforts to suppress German after the war, including a seven-year boycott against German scientists. The boycott, and the rise of the United States as a scientific power, boosted the standing of English.

Eventually, English would become the language to offer a way out of the scientific Tower of Babel. But it’s not that perfect solution scientists were hoping for a century ago.

“English does a lot of the things that Esperanto was originally intended to do,” Gordin says. “That comes with giving a huge advantage to native speakers of that language. Esperanto was supposed to be fair, and do that. And what we have now is something that does that, but isn’t fair.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.