Doctors still struggle to predict which patients with severe brain injuries will recover

Doctors have to make life and death decisions for patients with severe brain injuries, but they can’t always agree about the potential for recovery.

Listen 19:04

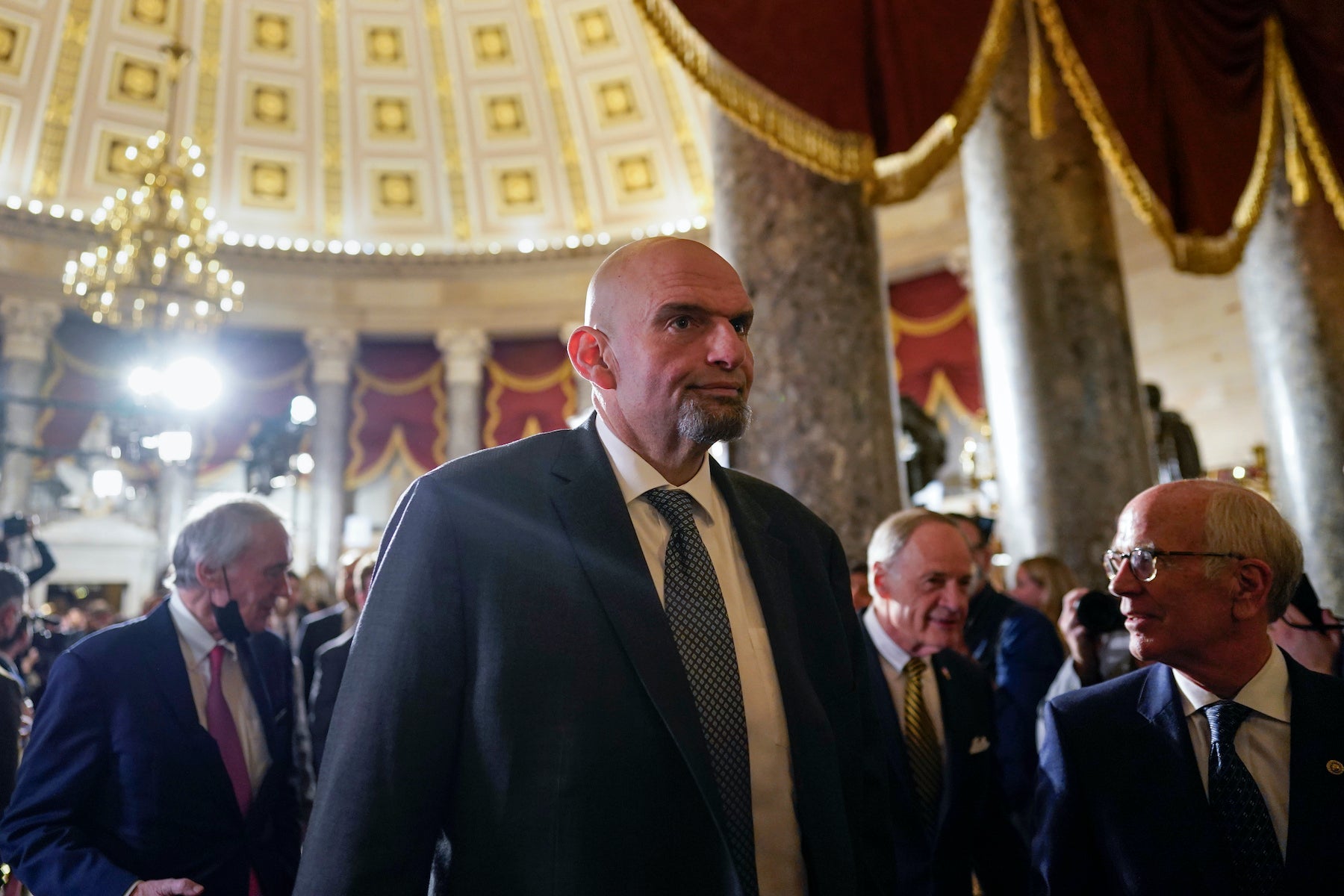

Two years ago, Cassie Wolfe suffered a stroke and fell into a coma. After months in this state, she finally woke up and had to relearn how to walk and talk. (Courtesy of Ann Louise Weaver)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Find our full episode on the mystery of consciousness here.

Two years ago, 23-year-old Cassie Wolfe went out dancing with her sister at a restaurant near Lebanon, Pa., and suddenly collapsed in the bathroom.

An ambulance rushed her to a hospital.

It turns out she had an undetected genetic heart condition, which stopped her heart and caused a stroke. She also suffered brain damage because of the oxygen loss.

At first, doctors thought she wouldn’t make it through the night. Wolfe survived but remained in a coma.

Her mother, Ann Louise Weaver, desperately wanted to know when her daughter might wake up, and when she would be able to talk to her. A doctor told her it would take at least three weeks.

“At the time I had no point of reference for how could it possibly take three weeks to have a conversation with her,” said Weaver. “It ended up that it was over two months, but at the time you just have no idea what the road ahead could be.”

When Wolfe’s condition stabilized, she was airlifted to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania to receive specialized care. Weaver rented an Airbnb and spent her days beside her daughter’s hospital bed.

She said doctors couldn’t give her precise answers about what Wolfe would be like if and when she woke up from her coma. They said she could recover well enough to only need help with tasks like filling out paperwork, or she could be awake but unaware of what’s going on around her, or anywhere in between.

Wolfe regained consciousness after two months, and slowly became able to communicate.

“It was like watching her all over again as a little baby, discovering her hands, discovering movement, listening to sound,” Weaver recalled. “It was really, like, endearing and beautiful, but also really scary to realize we’re starting over and not knowing what that was going to be like and what that was going to require from her and from us.”

She said that while it was a joy to have her daughter awake, it was also difficult because her daughter’s memory had also suffered. Wolfe did not immediately recognize Weaver, or one of her younger sisters.

“Her sister ran into the bathroom and just burst into tears and she was 16 at the time and was just devastated that Cassie had woken up, but didn’t know her name,” Weaver said. “There’s nothing like it — going through that process with a loved one, waiting for them to come back, but then when they do, they’re not who left you so quickly.”

Wolfe slowly regained her memories, and with the help of physical therapy, learned how to walk, write, and brush her teeth by herself.

“I was like, ‘That can’t be possible,’” Wolfe said. “It was a lot. I thought I could do all that, and then couldn’t even sit up straight.”

She left the hospital after three months, and now lives at home with her family. She still has physical therapy, and is working toward living by herself.

“It does very much feel like the world has passed us by and we’re in this strange, slow moving time warp all of our own,” Weaver said. “You keep the perspective that you’re practicing and you’re expanding to …create a new type of life that is more interactive and her tolerance for people and for busyness and for exertion. It is all growing, but slowly.”

Wolfe said her doctors are optimistic and told her she would be able to work and drive again.

“I don’t see that, but I don’t know what my heart and my brain will do together in the next few years,” she said. “It’s all up in the air. But I would love to try all that stuff again.”

The Challenges of Predicting Recovery

Patients who sustain severe brain injuries can lie unconscious for weeks, with their eyes closed. Their family members and loved ones want to know when they will become conscious again, and what kind of recovery they can make. But despite years of research and advanced brain scan technology, it’s still hard for doctors to predict how any given patient will do.

Neurologist David Fischer is one of the doctors who cares for Wolfe, and he’s created a program at the University of Pennsylvania dedicated to studying and helping patients like her. Doctors use different tests to check how much a patient’s brain has been damaged, and how well it is working, but they still struggle to estimate if, when, and how much a patient will recover, he said.

“Our ability to predict neurologic recovery is in general relatively poor,” Fischer said. “And so I think there’s diminishing nihilism about patients’ capacities to recover, and an increasing humility about predicting those recoveries.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

For instance, he said there have been studies where researchers sent data about a theoretical brain injury case to doctors around the country and asked for predictions. Those studies found that doctors are “all over the place.” And the predictions doctors make in these situations can have life or death ramifications.

“We see that variability translate into practice,” said Fischer. “There are other studies that have shown that physicians are highly variable in how we prognosticate for our actual patients. The rates at which we withdraw life support are highly variable. The concern is that if we are so variable in how we’re doing this, that we’re making some mistakes a certain portion of the time, and specifically are withdrawing life support prematurely for a subset of these patients.”

He said there are cases most doctors can agree on, but it becomes more complicated when patients have mild to moderately severe brain injuries. Also, these patients have to be treated at intensive care units so it can be hard to get a second opinion.

“So whichever doctor you happen to have been stuck with is the one who may be deciding whether they live or die,” he said.

Looking for Signs of Possible Recovery

These decisions are hard to make because even with advanced brain scans, the picture is not clear, said clinical neuroscientist Yelena Bodien at Vanderbilt University.

“You can actually look at a scan … and see global devastation: multiple parts of the brain are injured, there’s bleeding everywhere. And yet that person recovers. And you can see another scan where you don’t see clearly that much damage, and that person doesn’t recover. And so our tools that we’re using, in humans anyway, are just not sophisticated enough yet to see at a very granular level what exactly is happening enough to be able to correlate it or associate it with outcome.”

She and other researchers say every brain injury is different.

However, her work has shown that people who are seemingly unconscious could actually be aware to some degree of what’s happening, more so than doctors might have thought. Last year, she and other researchers published a paper looking at almost 300 people in the U.S. and Europe who could not respond to simple commands. But when they did brain scans, they found that some patients’ brains were responding, even if their limbs were not.

“You can’t see them wiggling their toes, but they can think about wiggling their toes, or they can think about opening and closing their hand, even though they don’t actually do it at the bedside.”

They concluded that one in four patients in that study showed this covert form of consciousness and could follow commands.

“That number is really staggering and … has shown the world … how prevalent this phenomenon is,” she said. “And has changed the conversation in many ways from: ‘This is something that might happen once in a while’ to ‘This is probably something that is occurring in many patients who are not conscious or appear to be not conscious.’”

Finding a Way Back from Brain Injury

How physicians view a patient’s potential for recovery can depend on what kinds of patients they see, said Jennifer Russo, a brain injury physiatrist at the Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation in New Jersey.

She explained that rehab specialists treat patients who survived; they see what is possible. Her colleagues in intensive care units work with patient families to make these life and death decisions, but they do not get the same picture

“They don’t get to the joy of getting to see people recover and they don’t always, get to see the potential that some of these patients can have,” Russo said. “It’s sort of been thought that someone who’s had a cardiac arrest or anything that’s prevented blood flow and oxygen to get to their brain, that universally guarantees a bad outcome. And the counseling that the families will get in that acute state is that they’ll never walk again, never talk again, never eat again, won’t live independently. And it’s not universally true. I have had multiple patients who are walking, talking, no feeding tube, no breathing tube, and are back to their lives. But I get to see that. I get that privilege.”

Michael Marino, a brain injury rehab specialist at Jefferson Moss-Magee Rehabilitation outside Philadelphia, has also witnessed several remarkable recoveries.

He recalled one of his patients who had a severe traumatic brain injury from a car accident, which killed this person’s father.

“He was so severely hurt that his family was .. that close to withdrawing care because …it looked very grim,” he said. “ In the end they decided not to, but it was very close, and he has made a recovery in which he is leading a fulfilling life.”

Marino also treated Leona Giordano’s son, Dom, who was seriously injured in a motorcycle accident almost two years ago.

He went from only moving his eyes in rehab to coming home to live with Giordano.

“Now he’s able to pick up his arm and point to yes, no. He can move his left arm and scratch his head, rub his nose, reach for things. We play Connect 4 now,” she said.

Jenn Tompkins suffered a serious brain injury in a car accident more than 10 years ago.

She is a little further along in her recovery.

She can walk around, and even was able to do office work a few hours a week at a time. She has some cognitive challenges with memory and complicated tasks, and also physical limitations that remain. “I don’t drive a car because my left side is like a stroke,” she explained. She wears braces on her left hand and foot to hold them in place. And she knows recovery is an ongoing journey. “I’m better, but determined still.”

Another one of Marino’s patients, Susan Arnhold, is more or less back to who she was, before being hit by a car while on her bicycle, more than four years ago.

She says she can tell how her brain is very different now, compared to when she first left the rehab center.

“In the beginning, if my husband started to talk to me, I’d say, ‘I can’t talk right now. I’m working on this thing and I can’t do two things at once.’ So that was the hardest thing as I was recovering — I realized I had to pay attention only to one thing at a time.”

She can now do most of the things she enjoyed doing before her injury – other than biking.

“I think that’s one thing I miss, I miss being on a ride in the sunshine on a real bike down the street. But I don’t think I’ve ever gotten my balance back quite the same as before. So I’m not willing to try it,” she said.

Despite these success stories, predicting outcomes is hard even for people like Marino who work with patients every day. “I’d be lying to you if I said we didn’t have, patients that didn’t do as well, patients that never regained consciousness, that never showed minimally conscious state.”

And so the challenge remains: how to tell which patients can make a recovery, what kind of recovery and what kind of future life awaits them.

Editor’s Note: This story was produced as part of a PBS “Renegades: American Masters” grant.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.