Digital demands paradigm shift in film archiving

Listen 7:34

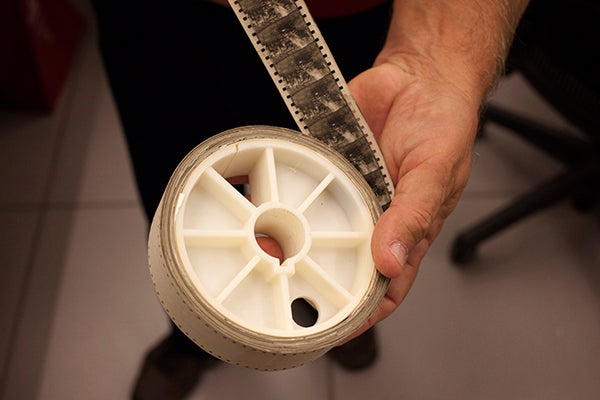

Reels of film wait to be catalogued in one of the Library of Congress warehouses. (Irina Zhorov/The Pulse)

At the Library of Congress Packard Campus of Audio-Visual Conservation, vaults burrow into Mount Pony on a 45-acre campus surrounded by bucolic, Virginia countryside.

The vaults used to hold gold – the facility belonged to the Federal Reserve before the Library took over – but now they’re full of film reels and video cassettes, among other artifacts of our audio-visual cultural heritage. The storage areas are kept cold – some sections register in the 30s Fahrenheit, others in the 50s – to maximize the longevity of the materials.

Paul Klamer, the Library’s video lab supervisor, took me on a brisk walk through the collections. In one warehouse, where uncatalogued materials are stored waiting for their date with an archivist, we passed stacks of film canisters and chronologically arranged piles of film machines. The Library keeps them around for parts.

In another section, we entered an area resembling a prison hallway, with metal doors, like those of cells, spaced together along both sides. Instead of prisoner names, the tags beside the doors listed movie studios: Columbia, Universal Pictures, etc. Behind each door was a room-sized vault containing old nitrate prints. Nitrate was a type of film base used in early cinema. The reason the collection is split up in these cells, or vaults, is because nitrate film is very flammable. If one vault ignites, water fills it in a matter of seconds, saving the rest of the collection.

In a different part of the archive, is yet another kind of storage area. Black cabinets full of disks and tapes hold thousands of terabytes of digital data. The room hums with cooling fans, and bright wires run in rivers along the ceiling. Just a small fraction of the Library’s collection is native digital or has been digitized from its original format, but the very presence of digital at the archives has transformed how archivists think of their work. And, though digital cinema has eased work in many aspects of cinema making and viewing, it’s actually made life a bit harder for cinema archivists.

Archive beginnings

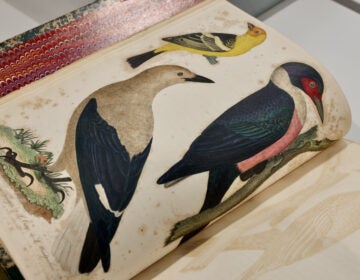

The archives of the moving image started by chance. In 1893 the Library received, through its copyright office, a roll of photographic paper 35 mm wide with printed images on it. Films weren’t even listed in the copyright office’s guidelines, yet, but the employee who processed it did so as a single work (rather than a series pf photographs). That was the first movie in the collection. Today, the Library is a collection of more than 6,000 so-called paper prints.

Eventually, movie makers started sending actual film. The archives’ millions of feet of film are also a happy coincidence. In the early 1900s, studios copyrighted big films, but not necessarily obscure ones, so many of those didn’t end up in the archive. And before TV made replaying old movies profitable, studios saw no reason to keep them. “There were legendary parties in Malibu where they burned nitrate prints of films, they’d just burn them on the beach, that was the firewood they brought,” Klamer said.

But the movies did have something going for them. The reels that didn’t end up in the fire turned out to be very archivable. You could put the film on a shelf, keep it dry and cool, and it would be around for hundreds of years.

Then, in the 2000s, the Library started to receive digital files. Archivists could no longer put stuff on a shelf. They had to develop a more active management strategy. Today, said Klamer, “we write it to hard drives, and then every three years, we copy it to new hard drives because they’re much faster and bigger, and then after some time we’ll write it to tape but those tapes, they get old and everybody knows they’re only going to last about 10 years.

The archivists have, for the most part, accepted the paradigm shift, but that doesn’t mean they’ve worked out all of the issues.

Digital dilemmas

To constantly migrate the archives is a logistical headache and more expensive, at least for now. With film, the Library had to invest in good shelving and pay for air conditioning. With digital, they pay for energy, but also the time and new drives or tapes to constantly update. It’s like investing in new shelves every couple of years. Though, it’s notable that digital storage continues to become bigger and better and to cost less.

Another problem is the lack of standardization of formats. Content producers send whatever they want to the copyright office. When the copyright office passes the file on to the archivists, it’s up to them to figure out what to do with it. Sometimes the files are encrypted, which is not good for the Library, but even when it’s not, it’s a hassle figuring out how to deal with each type of file.

Netflix has started asking for a standard file called an IMF, and the Library is sidling up to them, hoping content producers send the Library a copy of whatever they’re sending Netflix. They can work with the files, which contain a lot of data, and it would be a consistent format. However, that’s not formalized policy.

Meanwhile, the film itself isn’t going anywhere. But, infrastructure to maintain them as usable media – the projectors to play the films, the people to work the projectors, etc. – is aging.

The library has bought machines to start the process of digitizing everything. The machines include a scanner to digitally photograph the one hundred year old paper prints, large scanners for film, and robots that can run 24 hours per day copying videos. The library had to develop some of those new machines because they didn’t exist.

So far, less than one percent of the film has been digitized.

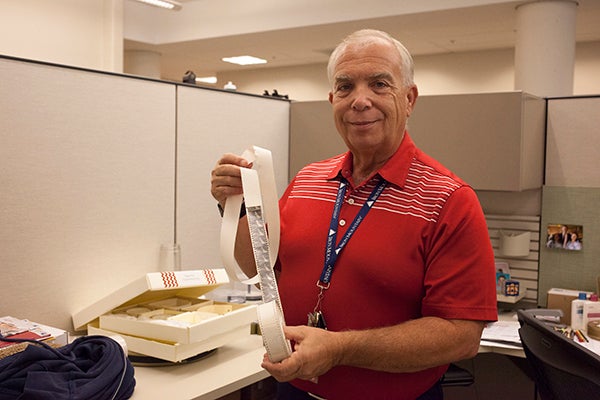

Ken Weissman, the supervisor of the Film Preservation Lab at the Library, said it’s only been a couple of years since the quality of the images on film could be translated to digital.

Another holdup has been developing the ability to handle such huge files. A single movie can be the equivalent of 160,000 individual photos and moving such massive files requires special infrastructure.

“I have pangs of film’s demise remorse,” Weissman said. The day I visited happened to be Weissman’s 35th work anniversary with the Library. “A number of years ago I really came to grips with the practical aspect of it, because my responsibility is to ensure that we can preserve the film. If film itself is on its way out then I have to make sure that I still meet my responsibilities and the alternative to that is film to digital workflows. So that’s what we’re about, that’s what we’re building. I wish things were different, but I understand the economics of it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.