Dental school grads find it hard to beat back student debt

Dentistry can be a lucrative career, but some say rising tuition costs mean massive loans to pay off in a changing market for care.

Listen 11:14

As tuitions climb faster than income levels, many dental school grads feel distressed about paying off huge amounts of student debt. (Courtesy of Lori Wilson)

Lori Wilson showed up for her first day of work at a dental clinic in Kotzebue, Alaska, wearing some questionable footwear.

“I had on these boots, and these boots had heels,” said Wilson, a general dentist. “The staff in the clinic, they had this bet. And that was that, ‘She’s not going to last two months.’”

Kotzebue, Alaska, is on a tundra 30 miles above the Arctic Circle. It’s surrounded by water on all sides, or ice in the winter. Temperatures of minus 80 degrees are normal. For Wilson, who is from Florida, it was a big leap from her comfort zone.

“When I got there, I was just like, ‘Oh, my God!’ I didn’t see any other Black people. It’s isolated. And it’s dark,” she said. “Almost six months out of the year, you’re in nothing but complete darkness.”

Some patients drove hours on a snowmobile or RV to see her. Or sometimes, she’d fly on a bush plane, then go by dog sled, to treat people in remote villages. It was lonely.

Wilson had to go that far to stay ahead of her student debt. When she graduated from dental school in 1995, she owed about $300,000. And she picked Kotzebue, Alaska, for a very specific reason.

“Kotzebue, Alaska, was No. 1 on the loan repayment lists,” she said. “That meant if you went there, it was more than likely that you would receive loan repayment.”

-

This is the first photo Lori Wilson took as a clinical dentist in Alaska, where she went in hopes of getting some help with loan repayment. (Courtesy of Lori Wilson)

She had joined the U.S. Public Health Service, which brings medical providers to high-need areas in the country. Those who heed the call can apply for a chance to get help in paying their student loans back — but there’s no guarantee.

About five months after Wilson got to Kotzebue, she got the letter she’d been hoping for. It said: Congratulations, we’re going to pay back some of your student loans. “That was the most wonderful thing that I could’ve ever had sent to me in my life,” she said. “Not the degree, not the license — that loan repayment letter.”

For every year she stayed in Alaska, the government would pay off $20,000 of her student debt, plus taxes.

“So it didn’t matter that I was isolated from my family. It didn’t matter that I lived on a tundra. It didn’t matter about there was no Walmart, no movie theater,” she said. “All that mattered to me was to get some of this debt paid off. And that’s what I did.”

Wilson, who now practices in Virginia, ended up staying in Alaska for three years. During that time, she made a decent dent on her loans.

‘These are mortgages on people’s brains’

Loan repayment programs like the one Wilson participated in are highly competitive.

For many people, debt from dental school is a constant source of anxiety.

Travis Hornsby is the founder of Student Loan Planner, a financial coaching company that helps people with huge amounts of student debt. Dental school students have always stuck out to him.

Among dental school grads with student debt, the average loan balance is around $285,000. Remember, that’s an average, Hornsby said. Some people come from wealth, and graduate with little debt. So, many owe a lot more.

“The typical dentists that we work with actually close in on about $400,000 of student loan debt,” Hornsby said. “So these are basically mortgages on people’s brains.”

-

Class of 2018 dental school graduates with student debt owed an average of $285,184. (Xavier Lopez/WHYY)

Actors struggle, artists struggle … but dentists? We don’t expect them to have serious financial worries. Hornsby breaks down some numbers.

“If you have almost $400,000 of debt, if you wanted to pay that back in 10 years, it would take you paying about $4,000 a month,” he said. “So that’s approximately $50,000 a year.”

How much do new dentists make? Well, dental school grads are facing a changing and tough market. Small mom-and-pop practices have given way to corporate group practices. Insurance companies cover very few dental services. And all around the country, adults are going to the dentist less often.

In a competitive job landscape, the starting salary for most dentists is around $120,000.

“After taxes, you’re probably going to take home about $80,000 or $90,000,” Hornsby said. So if you’re paying back $50,000 a year, you would “have to have more than half of your take-home pay go to debt for 10 years.”

Skyrocketing tuition

In recent decades, dental school tuition has increased much faster than inflation. If you look at what dental school cost in the 1980s and adjust it for inflation, today’s tuition is more than twice that.

And it’s only expected to get worse. A 2013 study found the ratio of debt-to-income to be increasing for dentistry, along with other professions that require higher education, such as medicine, veterinary medicine and law.

Why has tuition increased so much? Dean Mark Wolff, at the University of Pennsylvania, said one reason is that dentistry, in general, has gotten more expensive, and dental school has followed suit.

“You used to get the X-rays in your mouth taken with film, put inside your mouth. Today, we put sensors inside the mouth, capture it directly into the computer,” he said. “Film used to cost a few dollars a pack. That sensor is a $7,000 sensor.”

-

According to dental school administrators, one reason the cost of tuition has increased so much is that the technology required to practice dentistry has gotten more expensive. (Xavier Lopez/WHYY)

When asked about the exact break down of tuition dollars, Wolff said they’re not necessarily going into the classroom. “You need public safety, you need the halls swept and the bathrooms tended to.” There are also salaries, libraries, research and the costs of running the dental clinics that students see patients in.

Still, should new and aspiring dentists be completely overwhelmed by debt?

To that point, Bruce Donoff, dean of Harvard’s dental school, said, “Sour grapes.”

“Sour grapes — it’s still a very popular profession,” Donoff said. “I think there are a lot of programs that can reduce debt for people. But, you know, some of the inconsistencies here are a lot of students have very fine cars and live very well, and still have levels of indebtedness that were far beyond what I had.”

Charles Bertolami, dean of New York University’s College of Dentistry, one of the country’s most expensive dental schools, mentioned the same thing.

“There are some real horror stories out there that involve excessive living expenses,” he said.

Path of least resistance?

Asked what he thought about the deans’ responses, Travis Hornsby, the student loan coach, replied, “It’s absolute hogwash.”

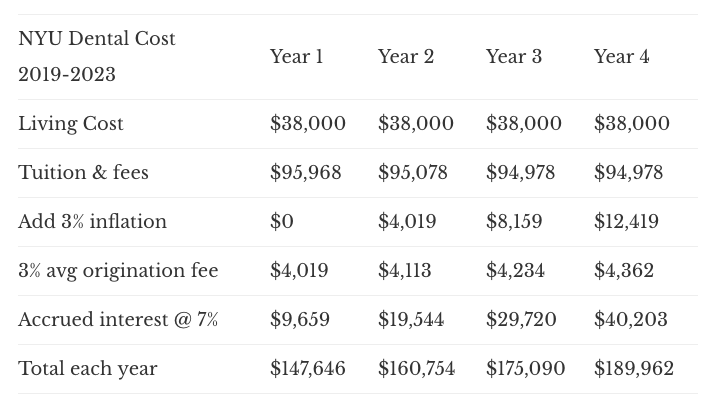

Hornsby used NYU as an example. Right now, the estimated four-year cost on the school’s website is nearly $400,000. Then add another $100,000 on top of that, “to represent loan fees, accrued interest, and the thing that everyone knows is coming, which is tuition increases,” he said.

That’s already $500,000 of dental school debt, if someone has zero living expenses. Now, say a student borrows $25,000 a year for living — penny-pinching, by New York standards. That’s another $100,000 of debt.

Throw in a little extra, Hornsby said, for “the interest fees and the origination fees that would pile on as well. So if somebody was an ultra-frugal dental student at New York University’s dental school, that person would leave in $625,000 of debt.”

By blaming students for their debt, Hornsby said, the deans are trying to distract from their own role. Dental schools are a business, he said. Compared with medical school, they tend to attract less money in donations, and have smaller endowments.

“So dental schools try to increase their revenue basically by charging directly,” he said. “I think dental school deans are just taking the path of least resistance.”

By that, he means that as long as there are students willing to pay — as long as there are more people applying than there are seats — dental schools will probably keep raising their prices. And dental students will keep taking out loans. Even if it’s $600,000 or $700,000. Federal Graduate Plus loans are uncapped, meaning students can take out as much money as they want, with no underwriting.

“So clearly, schools have no limit and no pushback on the price,” Hornsby said.

-

-

Student Loan Planner’s breakdown of costs at the NYU College of Dentistry. (Courtesy of Travis Hornsby/ Student Loan Planner)

On top of that, he added, schools are often not transparent or proactive about helping students navigate loans. In some cases, they’re even outright misleading.

-

“Deans will say something like, ‘The average time to paying back our loans is seven years,’” he said. “But if you look at a high-cost school, like some of the ones that you mentioned, that would take 100% of someone’s after-tax income to do that in a seven-year period. So somebody is not being totally truthful.”

‘I felt like I was being scammed’

One student heard from a school administrator that exact statistic, about students paying loans back in seven years.

He is currently taking a leave of absence from his dental school, to try to transfer to a cheaper one. The student spoke on the condition of anonymity; he was afraid that speaking up might jeopardize his chances of getting into another dental school, or make his life harder should he return to the school he is on leave from.

Based on the information his current school provided him, the student said, he underestimated the cost of his education by $150,000 when he first enrolled. By the time he understood that he’d owe more than $600,000 by graduation, it was too late to go to one of the other dental schools he’d gotten into.

He decided to do his first year while applying for scholarships, but he didn’t get any. During that year, he said, he felt perpetually hopeless and stressed.

“Gloom, just constantly hanging over my head,” he said. “I felt like I was doing myself a disservice and being financially irresponsible staying. I also felt like I was being scammed.”

He said that he talked to school administrators about his concerns multiple times, but felt dismissed every time. He asked a dean, who was also a professor of ethics, how ethical it was to tell students that graduates pay back their loans in seven years, when he knew from doing the math that the statistic was impossible.

He said the dean countered that students also behave unethically — for instance, by getting in-state tuition and then leaving that state as soon as they graduate.

“I thought… ‘How is that even an argument?’” the student said. “You’re an ethics professor, and you’re saying, ‘Hey, other people act unethically, so what’s wrong with us acting unethically?’”

He said he thinks dental schools are being predatory by continuing to raise their prices.

“I think that they’re price-gouging,” he said. “I don’t even know how they’re getting away with it.”

Feeling conflicted

Dental school debt doesn’t only affect dentists — it has implications for dental care.

Paul Gates, a retired dentist, researcher and clinical educator, spent his career trying to increase the recruitment of Black people into dentistry. He and other researchers have consistently found that Black dentists are more prone to practice in underserved areas, accept Medicaid, and treat Black patients.

There are many barriers responsible for the low number of Black dentists, Gates said, but one factor is that Black dentists bear more debt burden. About 50% of Black students graduate from dental school with debt exceeding $300,000 — compared with about 30% of white students.

Lori Wilson, who went to Alaska to pay down her debt, thinks about that often. She is president of an African American dental society in Virginia, the Peter B. Ramsey Society, through which she mentors young Black people who want to get into dentistry.

Right now, less than 4% of dentists are Black, and that’s a problem, she said.

“You have to understand, we actually treat our people,” she said. “If it wasn’t for us, a lot of African Americans would not be treated.”

Wilson wants more Black people to join the profession, but she also feels conflicted.

“I sometimes think about, you know, the kids that I’m mentoring, whether it’s right for me to encourage them to come into this profession and I know how much money they’re going to owe,” she said. “I think about that a lot of times.”

Excessive debt pressure also doesn’t make for good dentistry, Wilson said.

“In order to get as much money as you need to pay it off, you’re going to be seeing a whole bunch of patients. You’re going to be working yourself so you can’t even think straight,” she said. “And then the quality of your dentistry goes down. You have to think about each patient as a human being.”

-

Lori Wilson enjoys mentoring young people who want to pursue dentistry. This picture was taken at a cookout with minority students in their first year at the Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of Dentistry. (Courtesy of Lori Wilson)

Still, for Wilson, dentistry worked out. She sees patients every day and loves it. She feels proud to help people.

To her, the answer is to be honest about debt. She tries to prepare those she mentors — she urges them to look into scholarships, and to consider the most affordable dental schools and places to live.

“Just putting that knowledge in their head,” she said. “We’re trying to make sure that these students understand what they’re up against.”

Then, the decision is up to them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.